Abstract

The identification and analysis of different variable sources is a hot topic in astrophysical research. The Large Sky Area Multi-Object Fiber Spectroscopic Telescope (LAMOST) spectroscopic survey has accumulated a mass of spectral data but contains no information about variable sources. Although a few related studies present variable source catalogs for the LAMOST, the studies still have a few deficiencies regarding the type and number of variable sources identified. In this study, we present a statistical modeling approach to identify variable source candidates. We first cross-match the Kepler, Sloan Digital Sky Survey, and Zwicky Transient Facility catalogs to obtain light-curve data of variable and nonvariable sources. The data are then modeled statistically using commonly used variability parameters. Then, an optimal variable source identification model is determined using the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve and four credible evaluation indices such as precision, accuracy, recall, and F1-score. Based on this identification model, a catalog of LAMOST variable sources (including 631,769 variable source candidates with a probability greater than 95%, and so on) is obtained. To validate the correctness of the catalog, we perform a two-by-two cross-comparison with the Gaia catalog and other published variable source catalogs. We achieve the correct rate ranging from 50% to 100%. Among the 123,756 sources cross-matched, our variable source catalog identifies 85,669 with a correct rate of 69%, which indicates that the variable source catalog presented in this study is credible.

Original content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 licence. Any further distribution of this work must maintain attribution to the author(s) and the title of the work, journal citation and DOI.

1. Introduction

The study of variable sources has been one of the frontier topics in astronomy research and is also the core of many research topics in astrophysics (Eyer & Mowlavi 2008). For example, the study of eruptive and episodic systems can improve the understanding of accretion, mass loss, and stellar birth (Crawford 1955). Eclipsing systems constrain exoplanet demographics, mass transfer, binary evolution, and the mass–radius−temperature relation of stars. Pulsating sources are essential for probing stellar structure and stellar evolution theory (Walkowicz et al. 2009). In addition, some eclipsing systems and many of the most common pulsating systems (e.g., RR Lyrae, Cepheids, and Mira variables) are the fundamental means to measure precise distances to clusters, to the Local Group of galaxies, and to relic streams of disrupted satellites around the Milky Way (Kim et al. 2003; Richards et al. 2011).

Although variable sources have been studied for several hundred years, the discovery and identification of many variable sources rely heavily on the emergence of new detection tools. With the advent of the charge-coupled device, the Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment detected more than 900,000 variables during its 20 yr observation (Udalski et al. 1992, 2015). The first all-sky variability survey was carried out by the All-Sky Automated Survey, which contained eclipsing binaries and periodic pulsating sources (Pojmanski et al. 2005). Meanwhile, a series of catalogs of variable sources have been published based on different types of telescopes (Cioni et al. 2011; Drake et al. 2014, 2017). Subsequently, the development of time-domain astronomy has further promoted the identification of variable sources. A number of variable source catalogs were published, including the Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer catalog of periodic variable sources (Chen et al. 2018), the variable catalogs of Gaia DR2 (Clementini et al. 2019) and DR3 (Brown et al. 2021), the Zwicky Transient Facility (ZTF) catalog of periodic variable sources (Chen et al. 2020), and the catalog of over 10 million variable source candidates based on ZTF DR1 (Ofek et al. 2020).

The Large Sky Area Multi-Object Fiber Spectroscopic Telescope (LAMOST; Cui et al. 2012; Zhao et al. 2012) is a Schmidt telescope with an effective aperture of 3.6–4.9 m with the field of view of about 5°, which was designed to collect 4000 spectra in a single exposure (spectral resolution R ∼ 1800, limiting magnitude r ∼ 19 mag, wavelength coverage 3700–9000 Å). The LAMOST survey contains two main projects: the LAMOST ExtraGAlactic Survey and the LAMOST Experiment for Galactic Understanding and Exploration survey of the Milky Way stellar structure (Paunzen et al. 2021). At the end of 2020 September, the LAMOST DR6 catalog was officially released to the world. It includes the 4901 observation areas and 11.27 million spectral data. LAMOST provides valuable information on atmospheric parameters, which are essential parameters for variable source studies and can help make more accurate classifications and improve the classification accuracy of variable sources in combination with light curves. However, there is no variable source information in the current LAMOST catalog, imposing significant limitations on using LAMOST data for variable sources studies.

The issue of variable source identification for LAMOST catalogs has been studied in several related studies, and the corresponding catalogs have been published. Tian et al. (2020) presented a LAMOST radial velocity variable sources catalog. They first selected the sources observed multiple times in LAMOST and compared the observed radial velocity variation with the simulated radial velocity variation to estimate the probability of the radial velocity variable source. They finally obtained 80,702 radial velocity variable sources with a probability greater than 60%, and 3138 sources have been classified by cross-matching the data from other published catalogs. In addition, cross-matching with other catalogs is also a very effective way to identify variable sources for LAMOST. Ofek et al. (2020) obtained 10 million variable source data by standard deviation and period analysis methods, which contains several new short-period (less than 90 minutes) candidates, about 60 new dwarf nova candidates, two candidate eclipsing systems, and so on. They also provided cross-matching information with catalogs such as Gaia, the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS), and LAMOST.

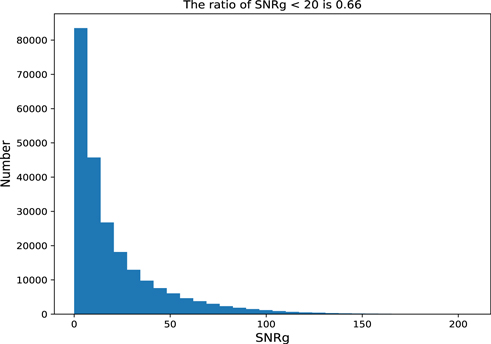

These works have effectively advanced the identification of variable sources for LAMOST. However, these works still have some minor limitations. For example, the identification method of Tian et al. (2020) is based on the radial velocity. The identification requires a sufficient number of observations of the variable source candidates. This results in a small number of variables and a low identification rate for other variable source types. The study of Ofek et al. (2020) is mainly based on the periodic analysis method, which works well for periodic variable sources but somewhat limits the discovery of other types of variable sources, especially aperiodic or long-period variables. In addition, the variable source catalogs presented by Ofek et al. (2020) and Chen et al. (2020) are limited in the number of sources that can be crossed with the LAMOST catalog. Although the catalog of Ofek et al. (2020) has 10 million variable sources, only 216,007 sources have been observed by the LAMOST. Of the 216,007 sources, 58% of the data have a signal-to-noise ratio in g band (S/Ng) less than 15, and 66% of the data have S/Ng less than 20. According to the data quality statement published on the LAMOST official website, data with an S/N less than 15 generally suffer from significant uncertainties in either radial velocity or stellar parameter estimation.

In this study, we tried a statistical modeling approach to the identification of LAMOST variable sources. The specific implementation is described in Section 2 in detail. We further apply these models to the data sets of LAMOST DR6 and ZTF DR2 and get the final catalog of LAMOST variable source candidates in Section 3. In Section 4, the catalog of LAMOST variable source candidates is evaluated by cross-identifying with the other variable sources catalogs obtained from different survey projects. And then, we make a discussion of the models and results in Section 5. Finally, we present the conclusion in Section 6.

2. The Identification Approach of Variable Sources Based on Light Curves

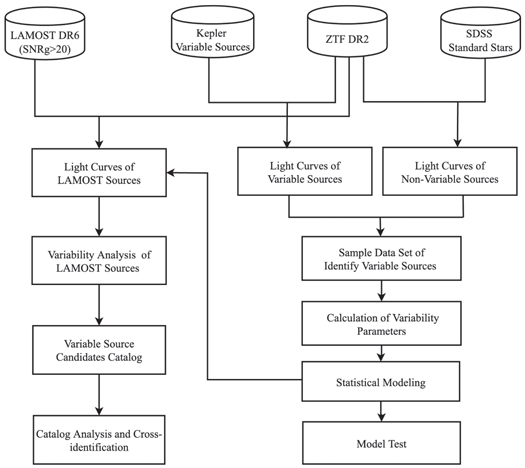

A statistical modeling approach was used in the study. The main idea is to first model the variability parameters by the light curves of variable and nonvariable sources. Then, the optimal model for the variability parameters is determined by model testing. Finally, the model is used to identify the variable source candidates. A data-flow diagram introducing modeling identification is shown in Figure 1. The entire statistical modeling process is divided into four main parts: searching trustworthy identification parameters, generating a sample set of light curves, creating statistical modeling for identification, and model testing.

Figure 1. The data-flow diagram of identifying variable sources for LAMOST sources.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution image2.1. Variability Parameters

The variability parameters of light curves are the keys for statistical modeling, ranging from basic statistical properties (e.g., mean, standard deviation, and so on) to more complex time-series characteristics (e.g., auto-correlation function).

According to the characteristics of light curves, we select seven variability parameters, i.e., Std, Iter-std, Cν , κ, γ, MAD, and Amp, from previous studies (Nun et al. 2015, 2017). These variability parameters have been proven to work well for classifying variable sources through a machine-learning approach (Cabral et al. 2018; Coughlin et al. 2021; van Roestel et al. 2021). In addition, we introduce three variability parameters (Q, Q1, and Q2). All parameters are described as follows.

(1) Q value (Q):

where mmax and mmin are the maximum and minimum magnitude in the light curves, respectively. Terms σmax and σmin are their magnitude measurement errors.

(2) Q1 value (Q1):

Q1 is a variant form of Q. After the maximum and minimum magnitude of the light curves are removed, we recalculated this parameter by the same calculation method as Q.

(3) Q2 value (Q2):

Q2 is also a variant form of Q. After removing the maximum, minimum, submaximum, and subminimum magnitudes of the light curves, recalculated this parameter by the same calculation method as Q.

(4) Standard deviation (Std):

where N is the number of detection times of light curves from the ZTF catalog, mi

is the magnitude of each observation in the light curves, and  is the mean of magnitude.

is the mean of magnitude.

(5) Iterative standard deviation (Iter-std):

After calculating the standard deviation of the light curve, the data other than the median plus or minus twice the standard deviation are removed, and the standard deviation is recalculated. This process is repeated until the resulting standard deviation converges to a stable value.

(6) Coefficient of variation (Cν ):

The Cν is a simple variability index and is defined as the ratio of the standard deviation to the mean magnitude. If a light curve has substantial variability, the Cν of this light curve is generally significant.

(7) Small kurtosis (κ): Small sample kurtosis of the magnitudes:

where  is the median of the magnitude. For a normal distribution, the small Kurtosis should be zero.

is the median of the magnitude. For a normal distribution, the small Kurtosis should be zero.

(8) Skewness (γ):

The skewness of a source is defined as follows:

For a normal distribution, it should be equal to zero.

(9) Median absolute deviation (MAD):

The MAD is described as the median discrepancy of the data from the median data:

A normal distribution should have a value of about 0.675. The interquartile ranges of a normal distribution can be used to illustrate this.

(10) Amplitude (Amp):

The amplitude is half of the difference between the median of the maximum and minimum 5% magnitudes. The amplitude of a set of numbers from 0 to 1000 should be 475.5.

2.2. Data Set Preparation

As described in the previous section, the statistical modeling approach seriously depends on data samples from sources. Constructing a credible data set from variable and nonvariable sources is the key to modeling.

1. Variable source data set

We built a variable source data set based on the variable sources explicitly labeled in the Kepler-related catalogs. The Kepler Space Telescope makes long-term continuous photometric observations in specific sky regions. A series of variable source catalogs based on these photometric data are published (Nielsen et al. 2013; Reinhold et al. 2013; Abdul-Masih et al. 2016; Bowman et al. 2016). The variable sources in the Kepler catalogs are accurately labeled. We first selected 12,151 rotating variable sources (Nielsen et al. 2013) and 983 pulsating variable sources (Bowman et al. 2016). In addition, a catalog of 2926 eclipsing binaries was selected from the Kepler website. 8 A total of 3752 common sources were obtained by cross-matching these Kepler variable sources with the ZTF catalog, and the light-curve data for these sources were obtained from the ZTF DR2.

2. Nonvariable source data set

To ensure the correctness of the nonvariable sources, we finally selected the light curves of the standard stars as the nonvariable source data set. Standard stars are used as benchmarks in astrophysics observations such as photometry and spectral classification, and usually, the magnitude of light curves is constant. Based on the multiple photometric observations of the SDSS, Ivezić et al. (2007) provided a standard star catalog that includes 1.01 million nonvariable unresolved objects. All sources are located near the equator. A total of 263,670 sources are obtained by cross-matching the SDSS standard stars catalog with ZTF DR2 catalogs. We also collected the light curves of these sources from ZTF DR2 to build the nonvariable data set.

Then, we randomly selected SDSS standard stars equal to the number of Kepler variable sources. The total number of the sample data set that we used in the statistical modeling is 7504. The distribution of detection times and the mean magnitude of light curves for these sources is shown in Figure 2. It shows the detection times of the standard stars are significantly less than that of the variable sources, and most of the standard stars are faint.

Figure 2. The statistical histograms of detection times and mean magnitude versus variable sources/standard stars distributions.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageTo further determine the availability of the standard stars, we counted the magnitude error distribution of the selected standard stars (see Figure 3). From the statistical histograms, the magnitude errors are within the 3σ level (N_3) for basically all of the standard stars, which indicates that the light curves of the standard stars are essentially constant.

Figure 3. The statistical histograms of sigma level versus variable sources/standard stars distributions.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageBased on the sample data set, we calculated the values of each of the 10 variability parameters. The results show significant differences between the values of the 10 parameters calculated by the variable sources and the nonvariable sources (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. The statistical histograms of Q and Q2 versus variable sources/standard stars distributions.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageMeanwhile, considering that the standard deviation may be affected by anomalous data in the light curves, we removed the anomalous values larger than two times the standard deviation from the light-curve data and then recalculated the standard deviation. After three iterations, the standard deviation finally calculated was treated as Iter-std. The statistical histograms for different values of Iter-std within three iterations for each variable source are given in Figure 5. The distribution of the variable sources gradually concentrates toward the direction where the value of Iter-std becomes smaller with continuous iterations. Eventually, the position with the highest number of variable sources is stabilized at about 0.014.

Figure 5. The distribution of standard deviation under three iterations for Kepler variable sources.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution image2.3. Statistics Modeling Based on Variability Parameters

We take the Q value as an example and introduce the corresponding modeling process. A total of 80% of the data in the sample set is used to perform statistical modeling, and the rest are used for model testing.

1. Source labeling

The first step is labeling all sources based on whether the source is a variable source or not. The label of the source Li is given by:

where S is the sample set, and Si is one source in the sample set. N is the number of sources in the sample set.

2. Variability parameter calculation

For each source Si , the corresponding variability parameter Vi is given by:

where V is the data set of the variability parameters.

3. Variability probability calculation

At first, Vi is sorted in ascending order, and Li is an expanded sort based on Vi . Then the variability probabilities P(Vi ) are calculated through the statistics of Li within an interval. This interval is 1% of the data of the sample set adjacent to Vi . The P(Vi ) is given by:

where P(Vi

) is the variability probability corresponding to Vi

and where  is the cardinality of the set

is the cardinality of the set  and

and  is the cardinality of the set

is the cardinality of the set  , respectively.

, respectively.

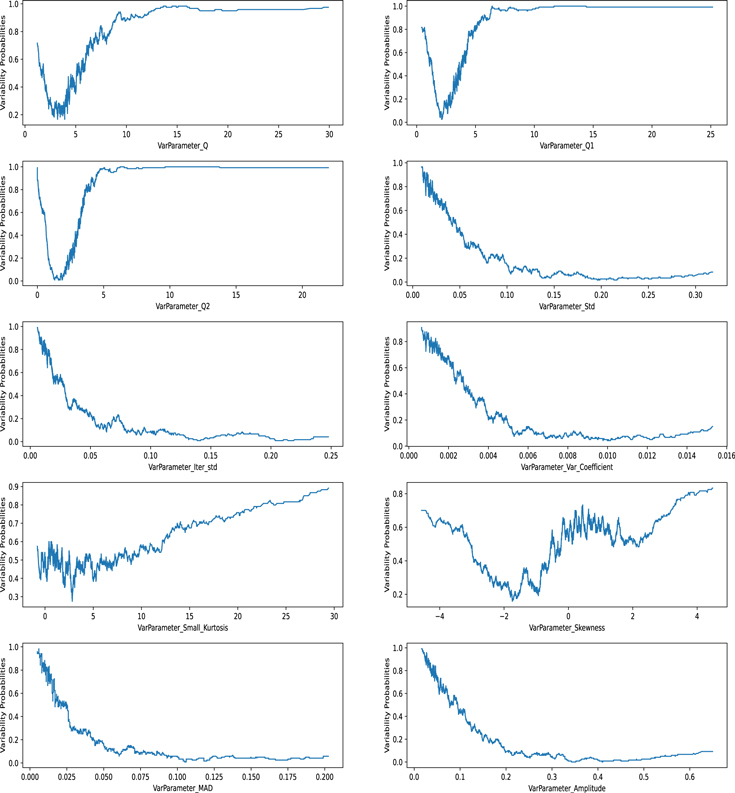

After the above three steps on the sample data set, we get the probabilities of the 10 variability parameters at different values (see Figure 6). These diagrams reflect the relationship between the variability parameters and the corresponding variability probabilities.

Figure 6. The variability probabilities at different variability parameters.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution image4. Variability parameters evaluation

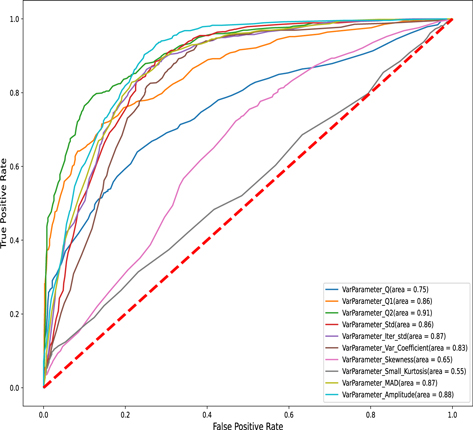

We take the variability parameter Q as an example to demonstrate the evaluating procedures. The evaluation for other variability parameters is consistent and will not be repeated here. Based on 20% of the data in the sample set, we counted the number of true positives (TP), true negatives (TN), false positives (FP), and false negatives (FN) under 100 variability probabilities ranging from 0 to 1. The accuracy, precision, recall rate, and F1-score were also calculated (Figure 7). Meanwhile, the ROC curve area of variability parameter Q is 0.75.

Figure 7. The performance of variability parameter Q at different variability probabilities.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageThe four credible evaluation indexes of the 10 variability parameters models under the different probabilities are presented in Tables 1 and 2. Moreover, the areas of ROC curves are shown in Figure 8. According to the evaluation results, the Q2 parameters have a better performance than the Q, Q1, Iter-std, Std, Cν , κ, γ, MAD, and Amp parameters. Therefore, our final identification model for variable source candidates is given by parameter Q2. Of course, the other nine variability parameters can still be used as a reference.

Figure 8. The ROC curves of the 10 variability parameters.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageTable 1. The Evaluation Indexes of 10 Variability Parameters (Probability ≥ 0.68% to Be Recognized as Variable Sources)

| Parameters | Accuracy | Recall | Precision | F1-score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q | 0.69 | 0.46 | 0.84 | 0.55 |

| Q1 | 0.77 | 0.62 | 0.89 | 0.69 |

| Q2 | 0.83 | 0.72 | 0.92 | 0.77 |

| Std | 0.77 | 0.71 | 0.80 | 0.74 |

| Iter-std | 0.78 | 0.71 | 0.82 | 0.74 |

| Cν | 0.76 | 0.73 | 0.78 | 0.75 |

| κ | 0.54 | 0.10 | 0.80 | 0.17 |

| γ | 0.53 | 0.09 | 0.73 | 0.16 |

| MAD | 0.79 | 0.73 | 0.83 | 0.76 |

| Amp | 0.76 | 0.73 | 0.78 | 0.75 |

Download table as: ASCIITypeset image

Table 2. The Evaluation Indexes of 10 Variability Parameters (Probability ≥ 0.95% to Be Recognized as Variable Sources)

| Parameters | Accuracy | Recall | Precision | F1-score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q | 0.53 | 0.07 | 0.98 | 0.12 |

| Q1 | 0.64 | 0.28 | 0.99 | 0.39 |

| Q2 | 0.69 | 0.38 | 0.99 | 0.49 |

| Std | 0.52 | 0.04 | 1.00 | 0.07 |

| Iter-std | 0.52 | 0.04 | 0.94 | 0.07 |

| Cν | 0.50 | 0 | NaN | 0 |

| κ | 0.50 | 0 | NaN | 0 |

| γ | 0.50 | 0 | NaN | 0 |

| MAD | 0.51 | 0.03 | 0.88 | 0.06 |

| Amp | 0.54 | 0.07 | 1.00 | 0.12 |

Download table as: ASCIITypeset image

3. The Identification of LAMOST Sources

The models of variable sources identification are constructed based on the variability parameters and statistical modeling. Therefore, in the follow-up LAMOST source identification, we calculated the variability parameters from the light-curve data. Moreover, we can obtain the final LAMOST variable source candidates based on the identification model.

3.1. Data Preparation

We selected the low-resolution data from LAMOST DR6 V1 with 9.91 million spectra, consisting of stars, galaxies, quasars, and other unknown objects. To ensure the quality of the spectral data, we limited the sample to data with S/Ng > 20 by referring to the related research of LAMOST data analyses (Liu et al. 2015; Wang et al. 2019). Finally, 4.68 million sources with high S/Ng spectra and position information were extracted from LAMOST data and saved to an IPAC table.

The light-curve data of these 4.68 million sources were matched from ZTF DR2 to identify variable sources. The ZTF DR2 contains light-curve data acquired between 2018 March and 2019 June, covering a time span of around 470 days (Graham et al. 2019; Masci et al. 2019). The ZTF DR2 includes more than 2 billion sources, about half of which have more than 20 observations (Bellm et al. 2019). These light-curve data can complement each other with the spectral data of the LAMOST, and the limiting magnitude and observational areas of the ZTF survey are close to those of the LAMOST survey. Referring to the pre-processing approach of Chen et al. (2020) and Ofek et al. (2020), we only used light curves from the g and r bands from the ZTF DR2 data set to match with the IPAC table that was generated previously. The i band is not considered at all because there is no target source in ZTF DR2 detected more than 20 times in that band.

At the same time, we attached two additional conditions to make the identification process of variable sources easier and quicker. (1) Low-quality images and photometry data were excluded by adopting INFOBITS < 33,554,432 and Catflags ≠ 32,768 (Masci et al. 2019). (2) We mainly selected sources in the ZTF DR2 data that were observed at least 50 times because the period's false-alarm probability (FAP) is relatively high based on fewer than 50 detections. After imposing the above two conditions and eliminating duplicate sources, we finally obtained 2.66 million LAMOST data sources.

3.2. Source Identification and Variable Source Catalog Generation

We performed variable source identification on LAMOST sources. After calculating the variability parameters obtained from light curves for each source, we determined whether the source is variable in the different variability parameters. Finally, we got the LAMOST variable source candidates based on the model of variability parameter Q2. As a result, all of the catalogs of LAMOST variable source candidates in the different probabilities and conditions are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. The Catalogs of LAMOST Variable Source Candidates (α is the Probability)

| Probability | α ≥ 95% | α ≥ 68% |

|---|---|---|

| Band | ||

| g band | 434,256 | 954,308 |

| r band | 324,139 | 738,365 |

| Union of g and r bands | 631,769 | 1,280,096 |

Download table as: ASCIITypeset image

We take the catalog that contains 631,769 LAMOST variable source candidates as an example, and list the detailed information in Table 4. This catalog contains the parameters provided by the LAMOST survey and the variability parameters obtained from the ZTF light-curve data and corresponding probabilities.

Table 4. LAMOST Variable Source Candidates Catalog

| R.A.(J2000) | Decl.(J2000) | ZTF_oid(g/r) | Q2(g/r) | P(Q2) (g/r) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 333.264311 | 1.835927 | 494101100004654/494201100007520 | 40.00/45.04 | 0.99/0.99 |

| 330.641667 | 1.239245 | 494102300003222/494202300005493 | 9.51/7.52 | 0.99/0.98 |

| 330.63137 | 1.835927 | 494102200004936/494202200009307 | 23.54/22.27 | 0.99/0.99 |

| 44.537916 | 0.952695 | —/453204400006321 | —/4.95 | —/0.98 |

| 10.08529 | 41.68036 | 695111200016244/695211200039474 | 9.50/12.27 | 0.99/1.00 |

| 10.214958 | 40.550835 | 695111300013377/695211300020792 | 6.38/5.69 | 1.00/0.95 |

| 81.4197442 | 29.6917296 | —/658201300022529 | —/4.82 | —/0.98 |

| 333.613593 | 29.758858 | 690101400006952/691204300010198 | 5.14/4.98 | 0.98/0.98 |

| 333.537014 | 30.355967 | 690101400008984/— | 5.64/— | 0.95/— |

| 333.974481 | 29.998455 | 691104300005030/691204300016607 | 9.25/11.73 | 0.99/1.00 |

| 333.768941 | 29.761166 | 691104300007551/— | 4.71/— | 0.97/— |

| 330.24329 | 30.66345 | 690102200008729/690202200013445 | 14.87/13.69 | 0.99/1.00 |

| 330.497222 | 31.192316 | 690102200001888/690202200002783 | 39.74/31.76 | 0.99/0.99 |

| 333.472737 | 32.11478 | 691208300004224/690105400002562 | 8.65/12.08 | 0.99/1.00 |

| 334.784969 | 31.591894 | —/691208400027388 | —/5.01 | —/0.98 |

| 330.698645 | 28.929285 | —/644215400001694 | —/12.45 | —/1.00 |

| 330.50609 | 29.093706 | 644115100020865/644215100014392 | 6.69/10.41 | 0.99/1.00 |

| 331.126246 | 28.929237 | 644114300001023/— | 5.85/— | 0.96/— |

| 331.094036 | 29.315796 | 644114200006522/644214200010240 | 6.04/4.76 | 0.98/0.97 |

| 333.593922 | 32.639942 | 690105100006583/691208200010470 | 6.66/6.11 | 0.99/0.99 |

Only a portion of this table is shown here to demonstrate its form and content. A machine-readable version of the full table is available.

Download table as: DataTypeset image

Table 5. The Performance of Variability Parameter Q2 for Variable Source Catalog of Ofek et al. (2020)

| Number of Variable Sources Randomly Selected from Ofek et al. (2020) | Number of Variable Sources Identified by Our Model | Rate |

|---|---|---|

| 10,029 | 9087 | 0.91 |

| 474,186 | 431,428 | 0.91 |

Download table as: ASCIITypeset image

4. Analysis and Evaluation for the Catalog

In this section, we cross-identify variable source catalogs previously published to evaluate our catalog of 631,769 LAMOST variable source candidates.

There are many catalogs of variable sources obtained from different survey projects, such as Kepler (Kirk et al. 2016), Gaia (Mowlavi et al. 2018; Roelens et al. 2018; Clementini et al. 2019), LAMOST (Tian et al. 2020), and ZTF (Chen et al. 2020; Ofek et al. 2020). These catalogs contain variable sources of different types, such as period variable sources, eclipsing binaries, RV variable sources, and so on. Thus, we use cross-identification to search for common sources between published variable source catalogs and LAMOST variable sources identified in the study and verify their correctness.

4.1. Cross-match with Gaia Variable Sources

The Gaia mission delivers nearly simultaneous measurements in the three observational domains on which most stellar astronomical studies are based: astrometry, photometry, and spectroscopy (Brown et al. 2016). The Gaia data releases provide accurate astrometric measurements for an unprecedented number of objects. In particular, trigonometric parallaxes carry invaluable information, since they are required to infer stellar luminosities, which form the basis of understanding much of stellar astrophysics.

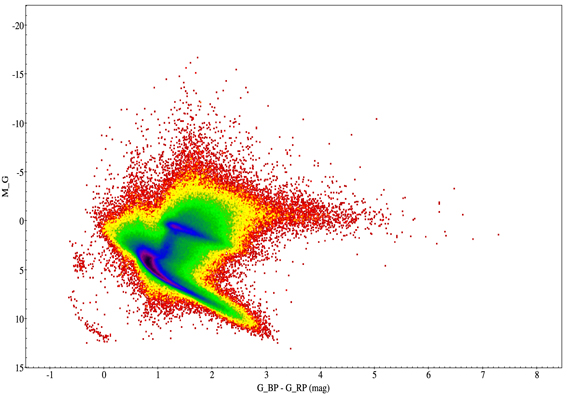

Based on these properties, the Gaia survey data can be complemented and verified with other telescope projects. The catalogs of LAMOST variable source candidates obtained in the study are also cross-match with the Gaia DR2 catalog in the Tool for OPerations on Catalogues And Tables (TOPCAT) software (Taylor 2005). The location distribution of LAMOST variable source candidates is obtained through the color−absolute magnitude diagram (CaMD), as well (see Figure 9).

Figure 9. The CaMD of the LAMOST variable source candidates. The G_BP—G_RP is the color of these candidates in the G band of Gaia DR2. The absolute Gaia magnitudes in the G band for individual sources are estimated using M_G = G + 5 + 5* , where G is the magnitude in the G band and ϖ is the parallax in milliarcseconds (Gaia Collaboration et al. 2018).

, where G is the magnitude in the G band and ϖ is the parallax in milliarcseconds (Gaia Collaboration et al. 2018).

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageIt can be seen from Figure 9 that the LAMOST variable source candidates in our catalog are concentrated in the main-sequence belt, followed by the giant star branch. By contrast, the white dwarf star sequence has fewer sources, which is consistent with the overall distribution of stars.

Gaia data include the Cepheids (Ceps), RR Lyrae (RRLs), long-period variables (LPVs), and short-period variables (SPVs; Clementini et al. 2019; Mowlavi et al. 2018; Roelens et al. 2018). There are 2106 common sources between the catalog of Gaia variable sources catalogs and LAMOST identification targets, and these sources are recognized as variable sources in our catalogs. The detection rate is 100% through our variability parameter models. Among them, these sources contain the 370 LPVs, 60 Ceps, 1667 RRLs, and 8 SPVs.

4.2. Cross-match with Catalog of Chen et al. (2020)

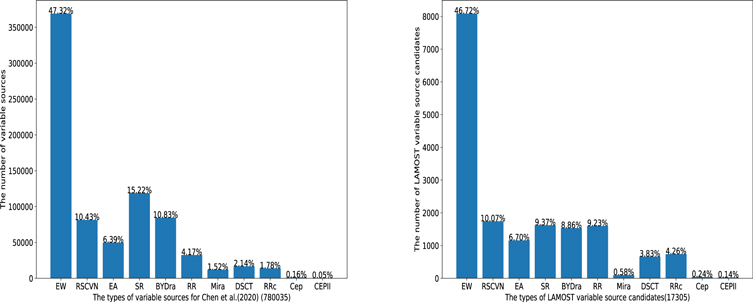

ZTF DR2 represents a highly suitable database for the detection and exploration of new variable source candidates. The catalog of 781,602 periodic variables was published by Chen et al. (2020). Comparison with previously published catalogs shows that 621,702 objects (79.5%) are newly discovered or newly classified, including ∼700 Cepheids, ∼5000 RR Lyrae stars, ∼15,000 δ Scuti variables, ∼350,000 eclipsing binaries, ∼100,000 long-period variables, and about 150,000 rotational variables.

However, we only selected the sources cross-matched between ZTF DR2 and LAMOST DR6 V1 and imposed a strict limit on the number of observations. Therefore, the data set used in our work is only a tiny fraction of the complete ZTF DR2. Nonetheless, there are 17,711 common sources between the catalog of ZTF DR2 periodic variable sources (PVSs) and LAMOST identification targets. Among them, 17,305 objects are recognized as PVSs with a probability of greater than 95%. Based on that, the detection rate of PVSs is about 98% through our variability parameter models. The distribution of the variable source types in our catalog is shown in Figure 10 through the cross-match with Chen et al. (2020). It is shown that our variability parameter model is valid for the most common types of variable sources.

Figure 10. The types distribution of variable sources. On the left is Chen et al. (2020), and on the right is our catalog cross-matched with Chen et al. (2020).

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution image4.3. Cross-match with Catalog of Ofek et al. (2020)

The catalog presented by Ofek et al. (2020) includes 10 million variable sources, the largest published catalog of ZTF variable sources. However, as mentioned in the previous section, only 216,007 sources can be cross-matched with LAMOST. The distribution diagram of S/Ng of these sources is shown in Figure 11. After removing data with S/N less than 20 and data points in the light curves less than 50, there are 71,454 common sources. Our model successfully identified 46,073 variable sources with a success rate of 64%. We also conducted a cross-match of the three variable catalogs. There are 7534 common sources among Ofek et al. (2020), Chen et al. (2020), and our LAMOST identification targets. These 7383 sources are included in our catalog.

Figure 11. The S/Ng distribution of LAMOST variable sources presented by Ofek et al. (2020).

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageWe further investigated the reasons that theses sources were not identified. We manually analyzed the light curves of a random sample of these sources. We note that the magnitude error of each photometric observation is given in the ZTF catalog. The magnitude variations of these unidentified sources are basically within the observed magnitude errors. Therefore, we realized that the difference between our results and those of Ofek et al. (2020) is due to the definition of variable sources. The variable sources identified in this study must have two observations with magnitude variations exceeding a factor of 2 magnitude error, while Ofek et al. (2020) selected variable candidates mainly based on specific thresholds under the robust std metric or the classical periodogram.

To validate this analysis, we directly examined the variable source data given by Ofek et al. (2020) using our given variability parameter (P(Q2) ≥ 68%). We randomly selected two variable source sets from (Ofek et al. 2020). Table 5 shows that our model successfully identified 91% of objects, proving that the Q2 is robust for variable identification.

4.4. Cross-match with Catalog of Kirk et al. (2016)

The Kepler Mission provided nearly continuous monitoring of 200,000 objects to an unprecedented photometric precision. The catalog of eclipsing binary systems within the 105° Kepler field of view was published by Kirk et al. (2016). This catalog lists the KIC, ephemeris, morphology, principle parameters, and so on. There are 859 common sources between the Kepler Eclipsing Binaries (EBs) and the variable catalog proposed in the study. Among them, 662 sources are identified as eclipsing binaries with a probability of greater than 95%. The detection rate of EBs is about 77% through our statistical model.

4.5. Cross-match with Catalog of Tian et al. (2020)

The LAMOST spectroscopic survey has provided ∼4.7 million unique sources that were targeted and ∼1 million stars that were observed repeatedly. The probabilities of stars being RV variables are estimated by comparing the observed radial velocity variations (RVVs) with simulated ones. The catalog of RVVs based on the LAMOST survey has been published by Tian et al. (2020). This catalog collects 80,702 variable sources, including 77% binary systems and 7% pulsating stars, as well as 16% pollution by single stars. There are 24,092 common sources between the LAMOST RVVs catalog and our LAMOST identification targets. Among them, 12,141 objects are recognized as RVVs with a probability of greater than 95%. The total detection rate of RVVs is about 50% through our variability parameter models.

At the same time, we also performed an additional cross-check with other catalogs. There are 12,141 common sources between our catalog with Tian et al. (2020), which is a rate of 1.9%, 1500 common variable sources between the Chen et al. (2020) and Tian et al. (2020) with a rate of 0.19%, and 686 common variable sources between Ofek et al. (2020) and Tian et al. (2020) with a rate of 0.0064%.

4.6. Performance of the Catalog

A summary of the numbers of common sources between the published catalogs and LAMOST identification targets is listed in Table 6. Note that some variable sources are identified repeatedly in different published variable sources catalogs. There are 123,756 common sources between our sources to be identified and the published catalogs such as the Gaia DR2 long-period variable sources, LAMOST RV variable sources, Kepler eclipsing binaries, and ZTF DR2 period variable sources. In total, 85,669 sources are detected as variable sources in our catalog with a probability of greater than 95% and are classified as different types. The detection rate of our catalog is 69% for the variable sources published in the catalogs referred to above.

Table 6. The Cross-identification between Our Catalog and Published Catalogs

| Published Catalogs | Common Sources with LAMOST Identification Targets | Identified by Our Model (α ≥ 0.95) | Identified Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clementini et al. (2019), etc. | 2106 | 2105 | 1.00 |

| Chen et al. (2020) | 17,711 | 17,305 | 0.98 |

| Ofek et al. (2020) | 71,454 | 46,073 | 0.64 |

| Chen et al. (2020) ∗ Ofek et al. (2020) a | 7534 | 7383 | 0.98 |

| Kirk et al. (2016) | 859 | 662 | 0.77 |

| Tian et al. (2020) | 24,092 | 12,141 | 0.50 |

| Total | 123,756 | 85,669 | 0.69 |

Note.

a Here, ∗ indicates the cross-match between two variable source catalogs, and α is the probability.Download table as: ASCIITypeset image

5. Discussion

5.1. Data Sets with Different Biases

The data sets containing the variable sources and standard stars are from different catalogs in the statistical modeling, which may have some potential biases due to the number of observations, types of sources, distribution of magnitudes, and so on. However, some minor biases exist from the same data set due to the influence of observing conditions, i.e., weather conditions and poor seeing. Therefore, constructing a completely unbiased data set is very difficult. Our study obtained the corresponding light curves of these sources collected from the ZTF DR2 by cross-matching with other catalogs, but we only rely on the ZTF light-curve data.

In addition, our nonvariable sources in the study were derived from the SDSS catalog of standard stars. Some new research suggests that some standard stars from different survey projects may be less than standard, which may affect the final results of this study. For this reason, in the statistical modeling, we only randomly selected standard stars with the same number of variable and nonvariable sources. In addition, we performed some experiments to replace the samples in the original data set with randomly selected data (1/2, 1/3, and 1/4) from the standard star catalog. We found a slight change in the evaluation index, but the variability parameter Q2 still performs the best, indicating that the results of this study are plausible.

5.2. Variable Source Identification Method

The identification method of variable sources is a very classical problem, and there has been a lot of preliminary research work. These methods are generally based on multiple photometric data, calculating the magnitude variance to determine whether it is a variable source, or using period analysis to determine whether it is a periodic variable source. The variable source identification method presented in the study draws fully on these methods. In the statistical modeling, we extract the corresponding targets in the ZTF by using the variable sources confirmed in the Kepler catalog and by statistically modeling the light-curve data of these targets. Compared with the classical method, the calculation is fast and straightforward, and is well suited for variable source identification in large-scale catalogs. Meanwhile, the experimental results show that the obtained accuracy is at least comparable to that of the conventional method. In addition, the statistical modeling method in this paper is a general identification method for different types of variable sources, which facilitates the classification of variable sources.

Of course, there are some limitations to this statistical modeling approach. For example, the number of observations of a source can directly affect the correctness of the identification. At the same time, a large accidental error in one photometric measurement may lead to a final misjudgment. In addition, our method is not sensitive to some special variable sources (outbursting stars, cataclysmic variables, and so on). For these types of variable sources, specific methods may be needed for identification, and we will consider this as a future work.

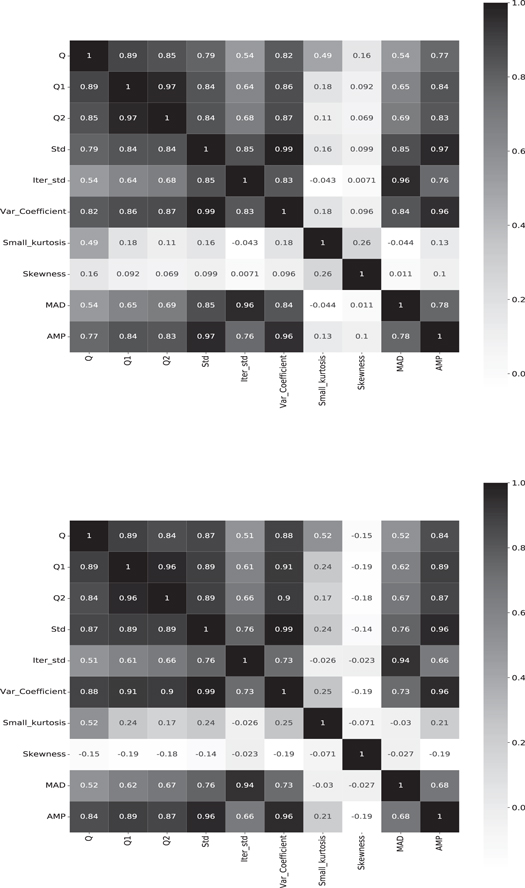

5.3. The Correlation Analysis of Variability Parameters

We performed a correlation analysis on the 10 variability parameters used for modeling, and the corresponding correlation coefficient matrix is shown in Figure 12. We see that linear relationships are present between all features to some extent, and most of them are positively correlated. Of course, these variability parameters still have other functional relationships, such as square relationships, logarithmic relationships, and so on.

Figure 12. The correlation matrix of 10 variability parameters for variable source candidates in two bands of the ZTF (top: g band; bottom: r band).

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution image5.4. The Limitations of Variability Parameter Models

In the process of variable source identification, 10 variability parameters (i.e., Q, Q1, Q2, Std, Iter-std, Cν , κ, γ, MAD, and Amp) are calculated based on the light-curve data obtained from ZTF DR2. These parameters are intrinsic statistical properties relating to the scale (Std, Iter-std), morphology (κ, γ, Amp), or other properties. These parameters are highly explainable and robust against bias (Cabral et al. 2018). However, they may also have varying utility. For example, the lack of some statistical attributes may affect the results of variable source identification. For example, the time statistical properties (Period) can reflect more information in the time-series data. In future work, we must consider introducing more parameters that contain more helpful information to identify variable sources.

6. Conclusion

The LAMOST survey has accumulated massive amounts of spectral data, but the research on variable sources is limited to a certain extent due to the lack of photometric information. We combined the light-curve data obtained from the ZTF time-domain survey to identify variable source candidates in this work. A catalog of 631,769 LAMOST variable source candidates is constructed with a probability of greater than 95%, and this process is based on the variability parameters and statistical modeling for light-curve data. This catalog is a robust database of variable source candidates. Moreover, the methods in this work are not only useful for the identification of periodic variables but also for general variables, including transient sources. They will be beneficial in a few future time-domain survey projects, such as WFST and MEPHESTO, under construction in China.

Meanwhile, the cross-identification and classification are carried out by matching with published catalogs. In total, 85,669 variable sources (with a probability greater than 95%) in our catalog are identified and classified, containing the Cepheids, RR Lyrae, eclipsing binaries, long-period variables, short-period variables, RV variable sources, and so on. Although recognized as variable sources, most of our catalog objects are not classified based on a data-match with other catalogs.

In further work, we will use spectral data and photometric information from LAMOST and other time-domain surveys to classify the catalog of variable sources as a follow-up to this work. Meanwhile, we will use machine-learning methods for variable source classification based on the calculated variability parameter of light-curve data. LAMOST has officially entered the mid-resolution surveys and is accumulating masses of spectral data. At the same time, future ZTF data releases will cover both increased time spans and large numbers of exposures. These aspects will help improve the identification of the long-period variables and increase the completeness of the catalog. In addition to the main types of variables discussed here, there are many cataclysmic variables, low-amplitude pulsating stars, binaries with compact objects, and stars with exoplanets. We will identify these variables to construct a large sample for further study based on future ZTF data releases and LAMOST data releases.

We thank the anonymous referee for valuable and helpful comments and suggestions. This work is supported by the National SKA Program of China No 2020SKA0110300, the Joint Research Fund in Astronomy (U1831204, U1931141) under cooperative agreement between the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) and the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), and National Science Foundation for Young Scholars (11903009), as well as by funds for International Cooperation and Exchange of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (11961141001), the Fundamental and Application Research Project of Guangzhou (202102020677), the Open funding of Key Laboratory of Solar Activity (KLSA202105), and the Innovation Research for the Postgraduates of Guangzhou University (2020GDJC-D20) have also supported this work. This work is also supported by the Astronomical Big Data Joint Research Center, co-founded by National Astronomical Observatories, Chinese Academy of Sciences and Alibaba Cloud.