ABSTRACT

We report Shanghai Tian Ma Radio Telescope (TMRT) detections of several long carbon-chain molecules in the C and Ku bands, including HC3N, HC5N, HC7N, HC9N, C3S, C6H, and C8H toward the starless cloud Serpens South 1a. We detected some transitions (HC9N J = 13–12, F = 12–11, and F = 14–13; H13CCCN J = 2–1, F = 1–0, and F = 1–1; HC13CCN J = 2–1, F = 2–2, F = 1–0, and F = 1–1; HCC13CN J = 2–1, F = 1–0, and F = 1–1) and resolved some hyperfine components (HC5N J = 6–5, F = 5–4; H13CCCN J = 2–1, F = 2–1) for the first time in the interstellar medium. The column densities of these carbon-chain molecules in the range 1012–1013 cm−2 are comparable to two carbon-chain molecule rich sources, TMC-1 and Lupus-1A. The abundance ratios are 1.00:(1.11 ± 0.15):(1.47 ± 0.18) for [H13CCCN]:[HC13CCN]:[HCC13CN]. This result implies that the 13C isotope is also concentrated in the carbon atom adjacent to the nitrogen atom in HC3N in Serpens South 1a, which is similar to TMC-1. The [HC3N]/[H13CCCN] ratio of 78 ± 9, the [HC3N]/[HC13CCN] ratio of 70 ± 8, and the [HC3N]/[HCC13CN] ratio of 53 ± 4 are also comparable to those in TMC-1. Serpens South 1a proves to be a suitable testing ground for understanding carbon-chain chemistry.

1. INTRODUCTION

Linear carbon-chain molecules like CnH, HC N and CnS have been observed to be abundant in cold dense clouds (Bell et al. 1997; Kaifu et al. 2004; Kalenskii et al. 2004; Langston & Turner 2007; Sakai et al. 2010b), in the circumstellar envelopes of carbon-rich asymptotic giant branch stars (Winnewisser & Walmsley 1978; Cernicharo & Guelin 1996; Guelin et al. 1997; Gong et al. 2015a), in massive star-forming regions (e.g., Feng et al. 2015; Gong et al. 2015b; Watanabe et al. 2015), in photo-dissociation regions (Pety et al. 2005; Gratier et al. 2013), and in diffuse clouds (e.g., Lucas & Liszt 2000; Liszt et al. 2012). The detection of these molecules has revealed that large organic molecules are forming in the interstellar medium (ISM). These species are proposed to be related to the formation and destruction of polyaromatic hydrocarbons (Henning & Salama 1998; Tielens 2008) and may be carriers of some diffuse interstellar bands. These molecules are also considered to be an evolutionary indicator of prestellar cores in star formation studies (Suzuki et al. 1992; Li et al. 2012). The full characterization of carbon-chain molecules is thus regarded as an important issue in astrochemistry (Sakai et al. 2010b).

N and CnS have been observed to be abundant in cold dense clouds (Bell et al. 1997; Kaifu et al. 2004; Kalenskii et al. 2004; Langston & Turner 2007; Sakai et al. 2010b), in the circumstellar envelopes of carbon-rich asymptotic giant branch stars (Winnewisser & Walmsley 1978; Cernicharo & Guelin 1996; Guelin et al. 1997; Gong et al. 2015a), in massive star-forming regions (e.g., Feng et al. 2015; Gong et al. 2015b; Watanabe et al. 2015), in photo-dissociation regions (Pety et al. 2005; Gratier et al. 2013), and in diffuse clouds (e.g., Lucas & Liszt 2000; Liszt et al. 2012). The detection of these molecules has revealed that large organic molecules are forming in the interstellar medium (ISM). These species are proposed to be related to the formation and destruction of polyaromatic hydrocarbons (Henning & Salama 1998; Tielens 2008) and may be carriers of some diffuse interstellar bands. These molecules are also considered to be an evolutionary indicator of prestellar cores in star formation studies (Suzuki et al. 1992; Li et al. 2012). The full characterization of carbon-chain molecules is thus regarded as an important issue in astrochemistry (Sakai et al. 2010b).

However, studies of long carbon-chain molecules have been seriously limited by the small number of detections. To date, long carbon-chain molecules have primarily been seen toward several nearby, low-mass star-forming regions, and in the envelope ofcarbon stars (Cernicharo & Guelin 1996; Bell et al. 1997; Guelin et al. 1997; Sakai et al. 2010b). For example, HC9N has been detected in two nearby molecular clouds, Taurus (Broten et al. 1978; Sakai et al. 2008) and Lupus (Sakai et al. 2010b), while HC11N has only been detected in TMC-1 (Bell et al. 1997). As a consequence, many problems related to the formation and chemistry of carbon-chain molecules remain poorly understood.

The decrease of abundance with increasing chain length is a key parameter for understanding the chemical reaction paths of carbon-chain radicals (Cernicharo & Guelin 1996). A steep drop off in the abundance of long CnH molecules have been seen in IRC +10216; for example, C8H was observed to be a factor of 6–10 less abundant than C6H (Cernicharo & Guelin 1996; Guelin et al. 1997). Bell et al. (1999) also found a steep fall-off in abundance of longer CnH chains in TMC-1, and they concluded that long CnH chains were less likely to be abundant in the diffuse gas. However, C8H was only detected in two molecular clouds, i.e., Lupus-1A (Sakai et al. 2010b) and TMC-1 (Bell et al. 1999). It is thus important to observe carbon-chain radicals toward more sources.

Given the astrochemical importance of carbon-chain molecules, their formation mechanism is still a matter of some controversy (e.g., Knight et al. 1986; Winnerwisser & Herbst 1987, p. 119), and the study of 13C isotopic fractionation provides a way to discriminate the formation mechanism (Takano et al. 1998; Furuya et al. 2011). Takano et al. (1998) observed the 13C substitutions of HC3N in TMC-1 and found significant differences in abundances among the 13C isotopic species, which differ from those in Sgr B2, Orion KL, and IRC+10216. Based on these results and on the reaction rate coefficients, they concluded that the most important formation reaction of HC3N is probably the reaction between C2H2 and CN. Abundance differences between the 13C isotopologues of CCS, CCH, C3S, and C4H were also found in TMC-1 (Sakai et al. 2007a, 2010a, 2013), and were believed to be caused by different formation processes or 13C isotope exchange reactions. Given that most of these studies are limited to the Taurus molecular cloud, more sources are needed to investigate whether the abundance difference among 13C isotopologues of carbon-chain molecules is general.

Friesen et al. (2013) detected multiple HC7N clumps within the young, cluster-forming Serpens South region in the Aquila rift. Their result extended the known star-forming regions containing significant HC7N emission from typically quiescent regions, like the Taurus molecular cloud (Kroto et al. 1978), to more complex, active environments. Nakamura et al. (2014) found that CCS is extremely abundant along the main filament in Serpens South, while a high CCS column density is typical of the carbon-chain producing regions suggested by Hirota et al. (2009). Detailed studies of this source will promote our understanding of the formation and destruction mechanisms of long carbon-chain molecules, thus we search for cyanopolyynes such as HC5N, HC7N, HC9N, hydrocarbons (e.g., C6H and C8H), and other carbon-chain molecules of astrochemical interest with the Shanghai Tian Ma Radio Telescope (TMRT) toward the strongest HC7N emission clump, Serpens South 1a, which lies directly to the north of a filamentary ridge.

2. OBSERVATIONS AND DATA REDUCTION

We performed observations of carbon-chain molecules in the Ku and C bands toward Serpens South 1a in 2015 May with the TMRT. The TMRT is a new 65 m diameter fully steerable radio telescope located in the western suburbs of Shanghai, China (Yan et al. 2015). Five cryogenically cooled receivers covering the frequency ranges 1.25–1.75 GHz (L), 2.2–2.4 GHz (S), 4.0–8.0 GHz (C), 8.2–9.0 GHz (X), and 11.5–18.5 GHz (Ku), are now available. The digital backend system (DIBAS) of TMRT is an FPGA-based spectrometer based on the design of the Versatile GBT Astronomical Spectrometer (Bussa 2012). For molecular line observations, DIBAS supports a variety of observing modes, including 19 single sub-band modes and 10 eight sub-band modes. The bandwidth of the a single sub-band mode varies from 1250 to 11.7 MHz. The spectrometer supports eight fully tunable sub-bands within a 1300 MHz bandwidth. The bandwidth of each sub-band is 23.4 MHz for modes 20–24 and 15.6 MHz for modes 25–29. The center frequency of the sub-band is tunable to an accuracy of 10 KHz.

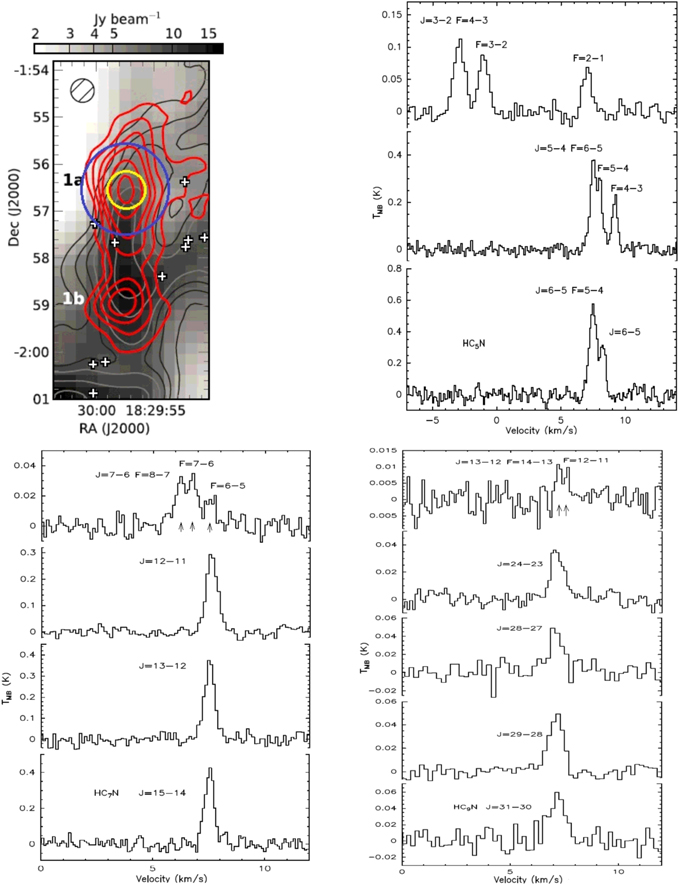

Figure 1 (upper left panel) shows the HC7N J = 21–20 and NH3 integrated intensities observed with the Robert C. Byrd Green Bank Telescope (GBT) overlaid as contours over the thermal continuum emission from dust at a sub-millimeter wavelength (André et al. 2010; Friesen et al. 2013). The 54″ FWHM TMRT beam at 18 GHz (yellow circle) and the 121″ FWHM TMRT beam at 8 GHz (blue circle) are shown. The coordinates adopted for our searches were R.A. (2000) = 18:29:57.9 and decl. (2000) = −1:56:19.0. The pointing accuracy is better than 12″. The DIBAS mode 20 was adopted for Ku band observation, with eight spectral windows, each of which has 4096 channels and a bandwidth of 23.4 MHz, supplying a velocity resolution of about 0.12 km s−1 (15 GHz) and 0.09 km s−1 (18 GHz) in the Ku band. The DIBAS mode 22 was adopted for C band observation, with eight spectral windows, each of which has 16384 channels and a bandwidth of 23.4 MHz, supplying a velocity resolution of about 0.05 km s−1 at 8 GHz. The intensities were calibrated by injecting periodic noise and the accuracy of the intensity calibration is 20%. The system temperature was about 30–80 K in the Ku band, and 20–50 K in the C band. We performed deep integrations to search for emission lines from HC9N, C6H, C8H, and the 13C substitutions of HC3N (H13CCCN, HC13CCN, and HCC13CN), reaching rms noise levels (σ) of 3–10 mK TMB in a smoothed resolution of about 0.1 km s−1. All the data were collected in the position switching mode. Both the on-source and off-source times were 3 minutes. The resulting antenna temperatures were scaled to the main beam temperatures (TMB) by using a main beam efficiency of 0.6 for a moving position of the sub-reflector in the Ku band, and a main beam efficiency of 0.6 in the C band (Wang et al. 2015). Table 1 lists the parameters of the observed lines, including the rest frequency, upper energy level Eu, FWHM beam, and rms noise in the emission free region. The rest frequencies and the uncertainties of observed lines were obtained from the molecular database at “Splatalogue,”3 which is a compilation of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (Pickett et al. 1998), Cologne Database for Molecular Spectroscopy (CDMS; Müller et al. 2005), and Lovas/NIST (Lovas 2004) catalogs.

Figure 1. Upper left: Herschel SPIRE 500 μm dust continuum emission (gray-scale; André et al. 2010) toward HC7N clump Serpens South 1a. Overlaid are NH3 (1, 1) integrated intensity contours (dark and light gray contours) and HC7N 21–20 integrated intensity contours (red, at intervals of 0.15 K km s−1). The 32″ FWHM GBT beam at 23 GHz is shown by the hashed circle. White crosses show class 0 and class I protostar locations (Friesen et al. 2013). The 54″ FWHM TMRT beam at 18 GHz (yellow circle) and 121″ FWHM TMRT beam at 8 GHz (blue circle) are shown. Upper right: spectral line profiles of HC5N in Serpens South 1a. The systemic velocity is 7.6 km s−1. Lower left: spectral line profiles of HC7N. Lower right: spectral line profiles of HC9N. The positions of the hyperfine components of HC7N and HC9N are indicated with arrows.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageTable 1. Observed Transitions and Telescope Parameters

| (1) Species | (2) Transitions | (3) Rest Freq. | (4) Eu | (5) Observing Date | (6) FWHM Beam | (7) rms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (MHz) | (K) | (″) | (mK) | |||

| HC5N | J = 3–2, F = 2–1 | 7987.779(0.005) | 0.8 | 2015 Jun 23 | 121 | 10 |

| J = 3–2, F = 3–2 | 7987.991(0.005) | 0.8 | ⋯ | 121 | 10 | |

| J = 3–2, F = 4–3 | 7988.041(0.005) | 0.8 | ⋯ | 121 | 10 | |

| J = 5–4, F = 4–3 | 13313.261(0.002) | 1.9 | 2015 May 8 | 73 | 16 | |

| J = 5–4, F = 5–4 | 13313.312(0.002) | 1.9 | ⋯ | 73 | 16 | |

| J = 5–4, F = 6–5 | 13313.334(0.002) | 1.9 | ⋯ | 73 | 16 | |

| *J = 6–5, F = 5–4 | 15975.9336(0.0001) | 2.7 | 2015 May 16 | 61 | 45 | |

| J = 6–5 | 15975.966(0.001) | 2.7 | ⋯ | 61 | 45 | |

| HC7N | J = 7–6, F = 6–5 | 7895.989(0.002) | 1.5 | 2015 Jun 23 | 123 | 5 |

| J = 7–6, F = 7–6 | 7896.010(0.02) | 1.5 | ⋯ | 123 | 5 | |

| J = 7–6, F = 8–7 | 7896.023(0.002) | 1.5 | ⋯ | 123 | 5 | |

| J = 12–11 | 13535.998(0.001) | 4.2 | 2015 May 8 | 72 | 14 | |

| J = 13–12 | 14663.993(0.001) | 4.9 | 2015 May 5 | 66 | 19 | |

| J = 15–14 | 16919.979(0.001) | 6.5 | 2015 May 16 | 57 | 34 | |

| HC9N | *J = 13–12, F = 12–11 | 7553.462(0.002) | 2.5 | 2015 Jun 23 | 129 | 3 |

| *J = 13–12, F = 14–13 | 7553.474(0.002) | 2.5 | ⋯ | 129 | 3 | |

| J = 24–23 | 13944.832(0.001) | 8.4 | 2015 May 16 | 70 | 6 | |

| J = 28–27 | 16268.950(0.01) | 11.3 | 2015 Jun 11 | 60 | 11 | |

| J = 29–28 | 16849.979(0.001) | 12.1 | 2015 Jun 11 | 58 | 4 | |

| J = 31–30 | 18012.033(0.001) | 13.8 | 2015 May 25 | 54 | 12 | |

| C3S | J = 3–2 | 17342.256(0.001) | 1.7 | 2015 May 5 | 56 | 51 |

| C6H |

J = 13/2–11/2, F = 7–6 e J = 13/2–11/2, F = 7–6 e |

18020.574(0.005) | 3.0 | 2015 May 22, 25 | 54 | 6 |

J = 13/2–11/2, F = 6–5 e J = 13/2–11/2, F = 6–5 e |

18020.644(0.005) | 3.0 | ⋯ | 54 | 6 | |

J = 13/2–11/2, F = 7–6 f J = 13/2–11/2, F = 7–6 f |

18021.752(0.005) | 3.0 | ⋯ | 54 | 6 | |

J = 13/2–11/2, F = 6–5 f J = 13/2–11/2, F = 6–5 f |

18021.818(0.005) | 3.0 | ⋯ | 54 | 6 | |

| C8H |

31/2–29/2 e 31/2–29/2 e |

18186.652(0.003) | 7.1 | 2015 May 22, 25, 26 | 53 | 5 |

31/2–29/2 f 31/2–29/2 f |

18186.782(0.003) | 7.1 | ⋯ | 53 | 5 | |

| HC3N | J = 2–1, F = 2–2 | 18194.9206(0.0008) | 1.3 | 2015 May 22, 25, 26 | 53 | 5 |

| J = 2–1, F = 1–0 | 18195.1364(0.0006) | 1.3 | ⋯ | 53 | 5 | |

| J = 2–1, F = 2–1 | 18196.2183(0.0005) | 1.3 | ⋯ | 53 | 5 | |

| J = 2–1, F = 3–2 | 18196.3119(0.0007) | 1.3 | ⋯ | 53 | 5 | |

| J = 2–1, F = 1–2 | 18197.078(0.001) | 1.3 | ⋯ | 53 | 5 | |

| J = 2–1, F = 1–1 | 18198.3756(0.0009) | 1.3 | ⋯ | 53 | 5 | |

| H13CCCN | *J = 2–1, F = 1–0 | 17632.6699(0.005) | 1.3 | 2015 May 22, 25, 26 | 55 | 3 |

| J = 2–1, F = 2–2 | 17632.685(0.007) | 1.3 | ⋯ | 55 | 3 | |

| *J = 2–1, F = 2–1 | 17633.7506(0.0005) | 1.3 | ⋯ | 55 | 3 | |

| J = 2–1, F = 3–2 | 17633.844(0.004) | 1.3 | ⋯ | 55 | 3 | |

| *J = 2–1, F = 1–1 | 17635.9084(0.0005) | 1.3 | ⋯ | 55 | 3 | |

| HC13CCN | *J = 2–1, F = 2–2 | 18117.727(0.0006) | 1.3 | 2015 May 22, 25, 26 | 54 | 3 |

| *J = 2–1, F = 1–0 | 18117.9441(0.0006) | 1.3 | ⋯ | 54 | 3 | |

| J = 2–1, F = 2–1 | 18119.029(0.005) | 1.3 | ⋯ | 54 | 3 | |

| J = 2–1, F = 3–2 | 18119.122(0.005) | 1.3 | ⋯ | 54 | 3 | |

| *J = 2–1, F = 1–1 | 18121.1825(0.0006) | 1.3 | ⋯ | 54 | 3 | |

| HCC13CN | *J = 2–1, F = 1–0 | 18119.6931(0.0005) | 1.3 | ⋯ | 54 | 3 |

| J = 2–1, F = 2–1 | 18120.773(0.002) | 1.3 | 2015 May 22, 25, 26 | 54 | 3 | |

| J = 2–1, F = 3–2 | 18120.865(0.002) | 1.3 | ⋯ | 54 | 3 | |

| *J = 2–1, F = 1–1 | 18122.9315(0.0005) | 1.3 | ⋯ | 54 | 3 |

Note. The asterisk  shows lines detected for the first time. Column (1): molecule name; Column (2): transition; Column (3): rest frequency; Column (4): Eu; Column (5): observing date; Column (6): FWHM beam; and Column (7): rms noise in the emission free channel, obtained from Gaussian fitting.

shows lines detected for the first time. Column (1): molecule name; Column (2): transition; Column (3): rest frequency; Column (4): Eu; Column (5): observing date; Column (6): FWHM beam; and Column (7): rms noise in the emission free channel, obtained from Gaussian fitting.

Download table as: ASCIITypeset image

The data processing was conducted using the GILDAS software package4 , including CLASS and GREG. Linear baseline subtractions were used for all the spectra. For each transition, the spectra of the subscans, including two polarizations, were averaged to reduce the rms noise levels.

3. OBSERVATIONAL RESULTS

We detected five transitions of HC9N, four transitions of HC7N, and three transitions of HC5N in the C and Ku band. The hyperfine structure of HC5N J = 6–5, F = 5–4 at 15974.9336 MHz was resolved for the first time. Ohishi & Kaifu (1998) detected HC5N J = 6–5 in TMC-1 with the Nobeyama 45 m radio telescope. The spectral resolution was 37 kHz (∼0.7 km s−1 at 15 GHz) in their observation. The separation between HC5N J = 6–5, F = 5–4 and HC5N J = 6–5 was 32 kHz, thus the hyperfine structure was not resolved at the time. Two hyperfine components of HC9N (J = 13–12, F = 12–11 at 7553.463 MHz and HC9N J = 13–12, F = 14–13 at 7553.474) were detected. The spectral line profiles of HC5N J = 6–5, HC7N J = 15–14, and HC9N J = 31–30 are also shown in Figure 1.

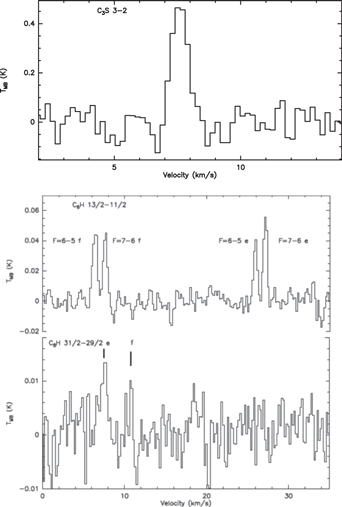

C3S 3–2 was detected with a peak intensity of 0.46 K. The spectral line profile of C3S J = 3–2 is shown in Figure 2 (upper panel).

Figure 2. Upper panel: the spectral line profile of C3S in Serpens South 1a. Lower panel: the spectral line profiles of C6H and C8H. Both show hyperfine structures due to the spin of the hydrogen nucleus.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageThe four fine and hyperfine structure components of the J = 13/2–11/2 transition of C6H were detected with a peak intensity of 52–76 mK. The doublet lines with partially resolved hyperfine structures of J = 31/2–29/2 lines of C8H were also detected. The intensity ratio of C6H to C8H is about 6:1. The spectral line profiles of the J = 13/2–11/2 transitions of C6H  and the J = 31/2–29/2 transitions of C8H

and the J = 31/2–29/2 transitions of C8H are shown in Figure 2 (lower panel).

are shown in Figure 2 (lower panel).

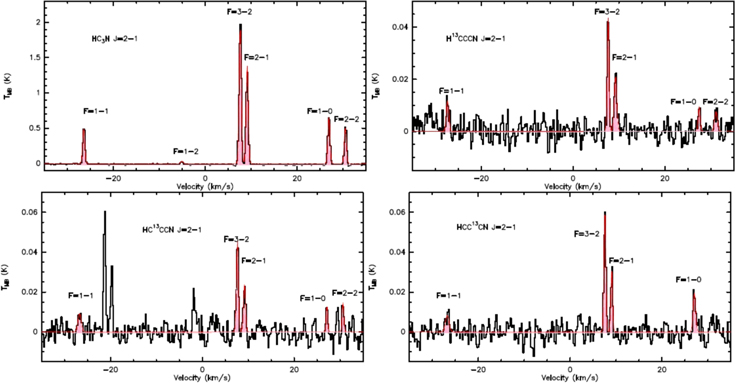

The 13C substitutions of HC3N (H13CCCN, HC13CCN, and HCC13CN) J = 2–1 were also detected. The spectral line profiles of HC3N and its 13C isotopomers are shown in Figure 3. The intensity of HCC13CN is stronger than HC13CCN and H13CCCN, with the difference in the peak intensities at a level of about 4σ (σ ∼ 4 mK). On the other hand, there is no significant difference in intensity between the HC13CCN and H13CCCN lines. This is similar to observations of TMC-1 (Takano et al. 1998). This result indicates that the abundance difference between H13CCCN and HC13CCN, and HCC13CN is not specific to TMC-1, but seems to be common to carbon-chain-rich clouds. H13CCCN J = 2–1, HC13CCN J = 2–1, and HCC13CN J = 2–1 have been observed in TMC-1 with the Nobeyama 45 m telescope (Ohishi & Kaifu 1998; Takano et al. 1998; Kaifu et al. 2004). Limited by their spectral resolution (37 kHz, ∼0.6 km s−1 at 18 GHz), the hyperfine components of these transitions were partially resolved. Resolved hyperfine components including the weak satellite components are detected for the first time here.

Figure 3. Spectral line profiles of HC3N, H13CCCN, HC13CCN, and HCC13CN. All of the lines show hyperfine structures. The red lines represent the hyperfine fitting using CLASS. All of the hyperfine components detected are filled with pink.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageThe line parameters are summarized in Table 2, including peak temperature (TMB), FWHM linewidth, centroid velocity, integrated line intensity ( ), and column density. These parameters and their errors are derived by fitting the Gaussian profile to each spectrum. Because the signal-to-noise ratio is not high enough, it is difficult to fit the weaker hyperfine component (

), and column density. These parameters and their errors are derived by fitting the Gaussian profile to each spectrum. Because the signal-to-noise ratio is not high enough, it is difficult to fit the weaker hyperfine component ( 31/2–29/2 e) of C8H well. We can see from Table 2 that the centroid velocities and FWHM linewidths of these carbon-chain molecule lines are similar, around 7.6 km s−1 and 0.6 km s−1, respectively, suggesting that these emissions come from similar regions. The linewidths are consistent with GBT observations of HC7N in this source (0.56 km s−1; Friesen et al. 2013). The linewidths are significantly higher than those in TMC-1 and Lupus-1A, which are reported to be 0.2–0.3 km s−1 (Li & Goldsmith 2012; Sakai et al. 2010b), implying that these emissions come from more complex and active regions than the other two sources.

31/2–29/2 e) of C8H well. We can see from Table 2 that the centroid velocities and FWHM linewidths of these carbon-chain molecule lines are similar, around 7.6 km s−1 and 0.6 km s−1, respectively, suggesting that these emissions come from similar regions. The linewidths are consistent with GBT observations of HC7N in this source (0.56 km s−1; Friesen et al. 2013). The linewidths are significantly higher than those in TMC-1 and Lupus-1A, which are reported to be 0.2–0.3 km s−1 (Li & Goldsmith 2012; Sakai et al. 2010b), implying that these emissions come from more complex and active regions than the other two sources.

Table 2. Line Parameters of Long Carbon-chain Molecules Detected in Serpens South 1a

| (1) Species | (2) Transitions | (3) TMB | (4)

|

(5) VLSR | (6)

|

(7) N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (mK) | (km s−1) | (km s−1) | (mK km s−1) | (cm−2) | ||

| HC5N | J = 3–2, F = 2–1 | 91(9) | 0.53(.05) | 7.63(.02) | 51(4) | ⋯ |

| J = 3–2, F = 3–2 | 129(9) | 0.59(.05) | ⋯ | 80(5) | ⋯ | |

| J = 3–2, F = 4–3 | 184(9) | 0.56(.03) | ⋯ | 109(5) | ⋯ | |

| J = 5–4, F = 4–3 | 243(13) | 0.50(.13) | ⋯ | 130(12) | ⋯ | |

| J = 5–4, F = 5–4 | 312(13) | 0.57(.13) | ⋯ | 190(12) | ⋯ | |

| J = 5–4, F = 6–5 | 348(13) | 0.41(.13) | 7.54(.13) | 151(12) | ⋯ | |

| *J = 6–5, F = 5–4 | 302(36) | 0.43(.04) | ⋯ | 138(12) | ⋯ | |

J = 6–5 J = 6–5 |

525(36) | 0.69(.03) | 7.51(.01) | 385(14) | 1.2(.1) × 1013 | |

| HC7N | J = 7–6, F = 6–5 | 18(3) | 0.56(.13) | ⋯ | 11(6) | ⋯ |

| J = 7–6, F = 7–6 | 29(3) | 0.40(.09) | ⋯ | 12(5) | ⋯ | |

| J = 7–6, F = 8–7 | 29(3) | 0.66(.18) | 7.55(.06) | 21(3) | ⋯ | |

| J = 12–11 | 291(10) | 0.60(.03) | 7.62(.01) | 186(6) | ⋯ | |

| J = 13–12 | 363(19) | 0.55(.02) | 7.53(.01) | 214(7) | ⋯ | |

J = 15–14 J = 15–14 |

415(38) | 0.50(.02) | 7.54(.01) | 220(8) | 6.0(.2) × 1012 | |

| HC9N | *J = 13–12, F = 12–11 | 11(1) | 0.31(.13) | 7.63(.04) | 4(1) | ⋯ |

| *J = 13–12, F = 14–13 | 10(1) | 0.28(.19) | ⋯ | 2(1) | ⋯ | |

| J = 24–23 | 52(5) | 0.44(.04) | 7.50(.01) | 24(2) | ⋯ | |

| J = 28–27 | 57(14) | 0.59(.12) | 7.57(.04) | 36(5) | ⋯ | |

| J = 29–28 | 65(3) | 0.58(.03) | 7.57(.01) | 41(2) | ⋯ | |

J = 31–30 J = 31–30 |

76(7) | 0.57(.05) | 7.62(.02) | 46(3) | 3.1(.2) × 1012 | |

| C3S |

J = 3–2 J = 3–2 |

502(28) | 0.72(.06) | 7.60(.03) | 385(28) | 1.0(.1) × 1013 |

| C6H |

J = 13/2-11/2, F = 7–6 e J = 13/2-11/2, F = 7–6 e |

48(2) | 0.66(.06) | ⋯ | 34(3) | 1.5(.1) × 1012 |

J =13/2–11/2, F = 6–5 e J =13/2–11/2, F = 6–5 e |

47(2) | 0.57(.6) | 7.64(.03) | 28(3) | ⋯ | |

J =13/2–11/2, F = 7–6 f J =13/2–11/2, F = 7–6 f |

41(2) | 0.49(.06) | ⋯ | 21(3) | ⋯ | |

a  J =13/2–11/2, F = 6–5 f J =13/2–11/2, F = 6–5 f |

59(2) | 0.54(.04) | ⋯ | 34(3) | ⋯ | |

| C8H |

31/2–29/2 e 31/2–29/2 e |

9(2) | 0.38(.86) | ⋯ | 4(2) | 8.2(.2) × 1011 |

a  31/2–29/2 f 31/2–29/2 f |

12(2) | 1.11(.29) | 7.45(.12) | 14(3) | ⋯ | |

| HC3N | J = 2–1, F = 2–2 | 557(2) | 0.55(.19) | ⋯ | 324(2) | 7.8(.4) × 1013 |

J = 2–1, F = 1–0 J = 2–1, F = 1–0 |

705(2) | 0.56(.19) | ⋯ | 420(2) | ⋯ | |

| J = 2–1, F = 2–1 | 1288(45) | 0.59(.19) | 7.60(.19) | 811(89) | ⋯ | |

| J = 2–1, F = 3–2 | 2014(45) | 0.60(.19) | ⋯ | 1280(89) | ⋯ | |

| J = 2–1, F = 1–2 | 39(4) | 0.66(.06) | ⋯ | 28(3) | ⋯ | |

| J = 2–1, F = 1–1 | 531(2) | 0.55(.04) | ⋯ | 313(2) | ⋯ | |

| H13CCCN | *J = 2–1, F = 1–0 | 8(2) | 0.76(.17) | ⋯ | 7(2) | 1.0(0.1) × 1012 |

| J = 2–1, F = 2–2 | 9(2) | 0.54(.18) | 7.77(.07) | 6(2) | ⋯ | |

| *J = 2–1, F = 2–1 | 21(2) | 0.67(.09) | ⋯ | 15(2) | ⋯ | |

J = 2–1, F = 3–2 J = 2–1, F = 3–2 |

44(2) | 0.48(.03) | ⋯ | 22(1) | ⋯ | |

| *J = 2–1, F = 1–1 | 12(2) | 0.64(.19) | ⋯ | 8(2) | ⋯ | |

| HC13CCN | *J = 2–1, F = 2–2 | 15(2) | 0.47(.12) | ⋯ | 8(2) | 1.1(.1) × 1012 |

| *J = 2–1, F = 1–0 | 14(2) | 0.45(.14) | ⋯ | 7(2) | ⋯ | |

| J = 2–1, F = 2–1 | 24(2) | 0.58(.08) | 7.65(.04) | 14(2) | ⋯ | |

J = 2–1, F = 3–2 J = 2–1, F = 3–2 |

45(2) | 0.53(.04) | ⋯ | 25(2) | ⋯ | |

| *J = 2–1, F = 1–1 | 9(2) | 0.81(.17) | ⋯ | 7(2) | ⋯ | |

| HCC13CN | *J = 2–1, F = 1–0 | 20(2) | 0.65(.13) | ⋯ | 14(2) | ⋯ |

| J = 2–1, F = 2–1 | 32(2) | 0.46(.06) | 7.56(.03) | 15(2) | 1.5(.1) × 1012 | |

J = 2–1, F = 3–2 J = 2–1, F = 3–2 |

62(2) | 0.49(.03) | ⋯ | 33(2) | ⋯ | |

| *J = 2–1, F = 1–1 | 12(2) | 0.50(.58) | ⋯ | 6(4) | ⋯ |

Note. Numbers in parentheses represent the errors in units of the last significant digits. The error of the column densities is one standard deviation. The asterisk * shows lines detected for the first time. a Lines used to derive the column density. Column (1): molecule name; Column (2): transition; Column (3): peak temperature; Column (4): linewidth; Column (5): centroid velocity; Column (6): integrated intensity; and Column (7): column density.

Download table as: ASCIITypeset image

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Column Densities of Carbon-chain Molecules

As shown in Figure 1, the size of the HC7N clump in Serpens South 1a is larger than the FWHM TMRT beam in the Ku band, but smaller than the FWHM TMRT beam in the C band. Thus it is inappropriate to estimate the rotational temperature and column density with rotational diagrams. Transitions in the 16–18 GHz range were used to derive the column densities of each molecule, and the lines that were used to derive column densities are labeled with “a” in Table 2. According to Figure 1, the size of the HC7N clump in Serpens South 1a is about 2 arcmin, therefore, the beam filling factor is ∼1. By assuming local thermodynamic equilibrium (LTE) conditions and optical thinness for all the molecules, the column densities of these species are estimated with the following equation (Cummins et al. 1986):

where k is the Boltzmann constant in erg K−1, W is the observed line integrated intensity in K Km s−1, ν is the frequency of the transition in Hz, and Sμ2 is the product of the total torsion–rotational line strength and the square of the electric dipole moment. Tex and Tbg (=2.73 K) are the excitation temperature and background brightness temperature, respectively. Eu/k is the upper level energy in K, and Q(Tex) is the partition function. The values of Eu/k and Sμ2 were taken from the “SPLATALOGUE” spectral line catalogs. Friesen et al. (2013) derived a kinetic temperature of 10.8 K from observation of NH3. Usually, the kinetic temperature is larger than the excitation temperature in starless cores. We adopt an excitation temperature of 7 K, which is similar to those in TMC-1 (Bell et al. 1998; Sakai et al. 2007a) and Lupus-1A (Sakai et al. 2010b). The partition function Q(Tex) of each molecule is estimated by fitting the partition function at different temperatures given in CDMS. For most of our molecules, increasing the excitation temperature by 2 K would increase or decrease the resulting column density by less than 10%. The maximum variation comes from HC9N, in which an increase in excitation temperature of 2 K would decrease the column density by 30%. The derived column densities and their errors are listed in Table 2. The errors come from the uncertainties of integrated intensities, which are obtained by Gaussian fitting. Decreasing the excitation temperature by 2 K would increase or decrease the resulting column density by less than 10% for most of our molecules. The maximum variations come from HC7N and HC9N, in which a decrease in excitation temperature of 2 K would increase the column density by 32% and 110%, respectively.

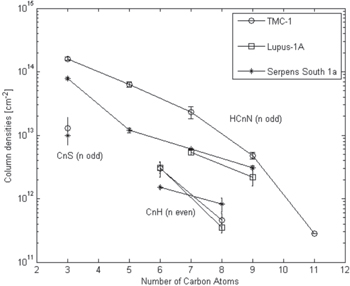

The column densities of these carbon-chain molecules range from 1012 to 1013 cm−1. Figure 4 shows a comparison of the column densities between Serpens South 1a, TMC-1, and Lupus-1A. We can see from Figure 4 that the column densities of long carbon-chain molecules in Serpens South 1a are comparable to those in TMC-1 and Lupus-1A (Sakai et al. 2010b). Thus we can say that the long carbon-chain molecules in Serpens South 1a are as abundant as in TMC-1. Therefore, like Lupus-1A, Serpens South 1a could also be regarded as a “TMC-1 like source.” This provides further evidence that the extraordinary richness of carbon-chain molecules in TMC-1 should not be ascribed to some special regional reasons, but should be considered as a more general phenomenon.

Figure 4. Comparison of the column densities between Serpens South 1a, TMC-1, and Lupus-1A. The 1σ errors of column densities are also shown. The column densities of Serpens South 1a are comparable to those of TMC-1 and Lupus-1A, thus Serpens South 1a could be regarded as another “TMC-1 like source.” The column densities of HC3N, HC5N, and HC11N in TMC-1 are taken from Takano et al. (1998), Takano et al. (1990), and Bell et al. (1997), respectively. The column densities of C6H and C8H in TMC-1 are taken from Sakai et al. (2007b) and Brünken et al. (2007), respectively. The column densities of C3S in TMC-1 are taken from Yamamoto et al. (1987). The column densities of the carbon-chain molecules in Lupus-1A are taken from Sakai et al. (2010b).

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageThe abundance ratio for HC7N:HC9N is (2.0 ± 0.2):1, which is similar to the abundance ratios found for TMC-1 and Lupus-1A, 4.8 and 2.5, respectively (Sakai et al. 2008, 2010b). The abundance ratio for C6H:C8H is calculated to be (1.8 ± 0.1):1, which seems to be less steep than the ratios observed in TMC-1 and Lupus-1A, 6.5 and 10, respectively (Brünken et al. 2007; Sakai et al. 2008, 2010b). However, it should be noted that the column density is derived from one rotational transition of each molecule in this paper. In this case, the column densities of C6H and C8H (or HC7N and HC9N) are derived from transitions with different upper-state energies (see Table 1). So variation of the rotation temperature will affect the column densities for the two molecules differently. In general, the rotation temperature tends to be higher for longer chains (e.g., Bell et al. 1998; Ohishi & Kaifu 1998). As calculated above, if the rotation temperature of HC9N is higher than HC7N by 2 K, the abundance ratio for HC7N:HC9N could be higher by ∼30%. If the rotation temperature of C8H is higher than C6H by 2 K, the abundance ratio could be higher by about 3%. Our results suggest that the abundance ratio for HC7N:HC9N is similar to those in TMC-1 and Lupus-1A, while the abundance ratio for C6H:C8H is statistically significantly lower than those in TMC-1 and Lupus-1A.

4.2. Abundance Ratio of HC3N Isophomers

The study of 13C isotopic fractionation provides a way to discriminate the formation mechanism of carbon-chain molecules (Takano et al. 1998). Numerical calculations suggest that molecules formed from carbon atoms have carbon isotope ratios (CX/13CX) greater than the elemental abundance ratio of [12C/13C], while molecules formed from CO molecules have CX/13CX ratios smaller than[12C/13C] (Furuya et al. 2011). We investigate the 13C isotopic fractionation with observations of 13C isotopologues of HC3N in Serpens South 1a.

The HC3N 2–1 transition has six hyperfine components, all of which were clearly seen in our spectra. We calculated the optical depth of HC3N using the “hfs” fitting method (McGee et al. 1977) in the GILDAS CLASS package and found that it is optically thin, with an optical depth smaller than 0.1, see Figure 3. This is obviously smaller than in TMC-1, in which an optical depth of 0.47 was obtained from the HC3N J = 2–1 transition (Li & Goldsmith 2012), suggesting that the column density of HC3N in Serpens South 1a should be lower than that in TMC-1 at the same temperature. The column densities of the normal and the 13C isotopomers of HC3N were calculated assuming LTE using Equation (1), also with the excitation temperature of 7 K. The integrated intensity (W) and Sμ2 of the strongest hyperfine components were used to derive the column densities for the 13C isotopomers of HC3N. We did not use the strongest component to derive the column density of the normal HC3N because of its larger uncertainty in comparison with other components. Lines that were used for analysis were labeled with “a” in Table 2. The column densities obtained are listed in Table 2. The column density of normal HC3N was comparable to that of TMC-1 ((1.6 ± 0.1) × 1014 cm−2; Takano et al. 1998). The ratios of the column densities of the three 13C isotopic species are 1.00:(1.11 ± 0.15):(1.47 ± 0.18) for [H13CCCN]:[HC13CCN]:[HCC13CN]. The results presented here are similar to TMC-1, in which the abundance ratios are observed to be 1.0:1.0:1.4 for [H13CCCN]:[HC13CCN]:[HCC13CN] at the cyanopolyyne peak of TMC-1. This result implies that the 13C isotope is also concentrated in the carbon atom adjacent to the nitrogen atom in HC3N, which supports the idea that C2H2+CN is probably the most important reaction in producing HC3N (cf. Takano et al. 1998).

The carbon isotopic ratios (12C/13C) were further calculated from the obtained column densities of the normal and isotopic species of HC3N. The carbon isotopic ratios obtained from H13CCCN, HC13CCN, and HCC13CN are 78 ± 9, 70 ± 8, and 53 ± 4. The average 12C/13C (∼67 ± 7) does not significantly deviate from the value of ∼70 in the solar neighborhood (Wilson & Rood 1994).

The [HC3N]/[H13CCCN], [HC3N]/[HC13CCN], and [HC3N]/[HCC13CN] ratios were derived to be 79 ± 11, 75 ± 10, and 45 ∼ 55 in TMC-1 (Takano et al. 1998). Therefore, the [HC3N]/[H13CCCN] and [HC3N]/[HC13CCN] ratios are similar for TMC-1 and Serpens South 1a. Langer & Graedel (1989) modeled the time evolution of the 12C/13C ratios of various species with an ion–molecule chemistry of nitrogen-, oxygen-, and carbon-bearing molecules and isotopic ratios. They found that the ratios depend sensitively on physical conditions like temperature and density, implying similar physical evolutionary stages for Serpens South 1a and TMC-1. Observations toward more sources are needed to obtain a full understanding of the behavior of 13C species in molecular clouds.

5. SUMMARY

We carried out carbon-chain molecular line observations toward Serpens South 1a with the TMRT. Several carbon-chain molecules were detected, including HC5N, HC7N, HC9N, C3S, C6H, C8H, and 13C substitutions of HC3N. For the first time, some transitions and hyperfine components from HC5N, HC9N, and 13C substitutions of HC3N were detected or resolved.

We calculated the column densities of these molecules and found that the column densities of these carbon-chain molecules in Serpens South 1a are comparable to those in two other carbon-chain molecule rich sources, TMC-1 and Lupus-1A. Thus this source could be regarded as another “TMC-1 like source.” The column density ratio of HC7N:HC9N is similar to those in TMC-1 and Lupus-1A, while the abundance ratio of C6H:C8H seems to be statistically significantly lower than those in TMC-1 and Lupus-1A.

We also derived the abundance ratios of HC3N isophomers, and made a comparison with TMC-1. We found an average 12C/13C ratio of about 67 ± 7, which does not significantly deviate from the value in the solar neighborhood. There is no difference in the carbon isotopic ratios between TMC-1 and Serpens South 1a, reflecting similar physical evolutionary conditions for these two sources.

We would like to thank the anonymous referee for his/her very constructive suggestions that led to significant improvements in the paper. We also thank the assistance of the TMRT operators during the observations. J.L. wishes to thank Y. Gong for help with the calculation of column densities. This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants 11590780, 11590784, and 11103006), National Basic Research Program of China (973 program) No. 2012CB821800, the Strategic Priority Research Program “The Emergence of Cosmological Structures” of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Grant No. XDB09000000, the Knowledge Innovation Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant No. KJCX1-YW-18), and the Scientific Program of Shanghai Municipality (08DZ1160100).