Abstract

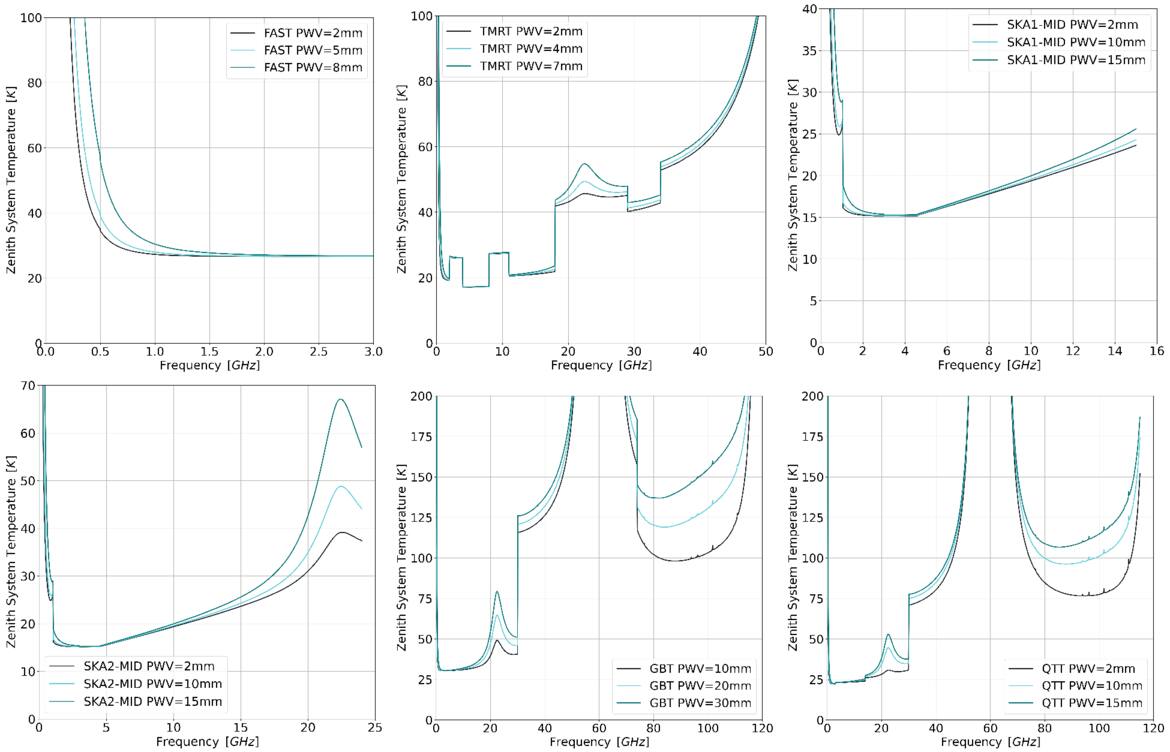

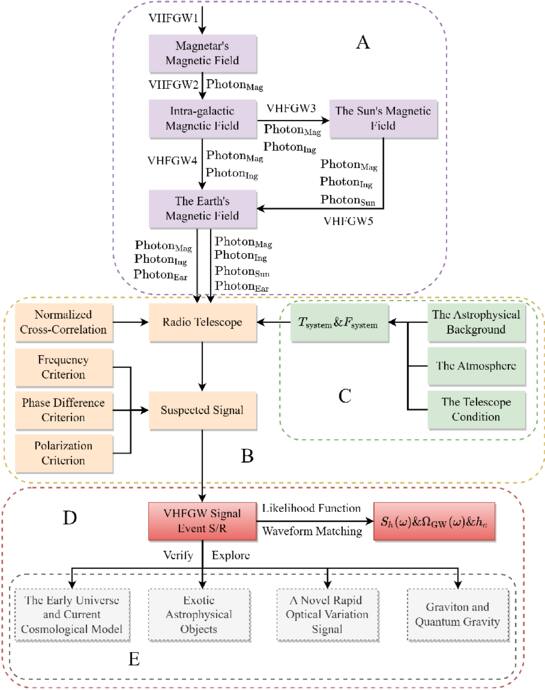

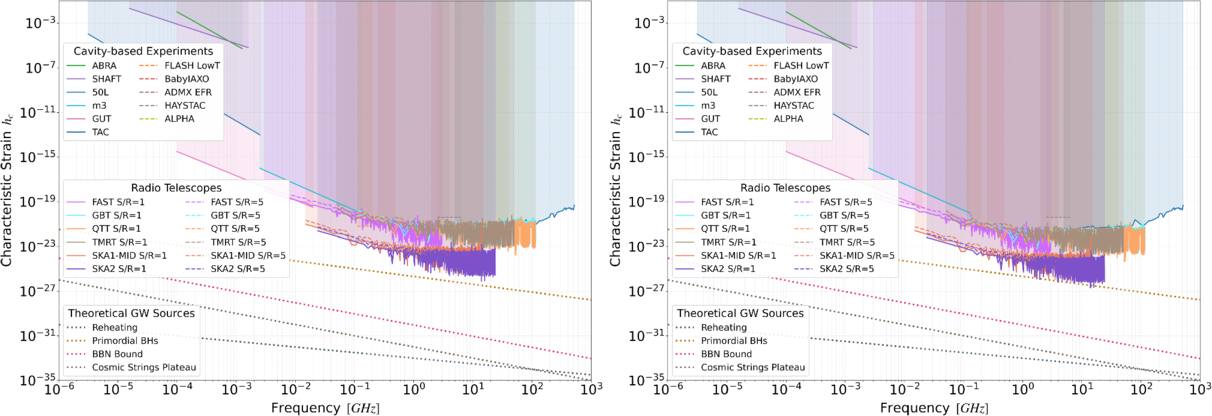

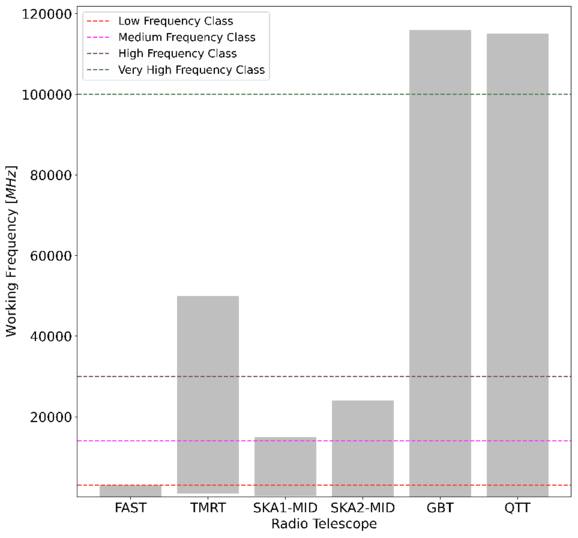

Gravitational waves (GWs) can convert into electromagnetic waves in the presence of a magnetic field via the Gertsenshtein–Zeldovich effect. The characteristics of the magnetic field substantially affect this conversion probability. This paper confirms that strong magnetic fields in neutron stars significantly enhance the conversion probability, facilitating detectable radio signatures of very high-frequency (VHF,  ) GWs. We theoretically identify two distinct signatures using single-dish telescopes (FAST, TMRT, QTT, GBT) and interferometers (SKA1/2-MID): transient signals from burst-like GW sources and persistent signals from cosmological background GW sources. These signatures are mapped to graviton spectral lines derived from quantum field theory by incorporating spin-2 and mass constraints, resulting in smooth, featureless profiles that are critical for distinguishing GW signals from astrophysical foregrounds. FAST attains a characteristic strain bound of hc < 10−23, approaching 10−24 in the frequency range of 1–3 GHz with a 6 hr observation period. This performance exceeds the 5σ detection thresholds for GWs originating from primordial black holes and nears the limits set by Big Bang nucleosynthesis. Additionally, projections for SKA2-MID indicate even greater sensitivity. Detecting such GWs would improve our comprehension of cosmological models, refine the parameter spaces for primordial black holes, and function as a test for quantum field theory. This approach addresses significant deficiencies in VHF GW research, improving detection sensitivity and facilitating the advancement of next-generation radio telescopes such as FASTA and Square Kilometre Array, which feature larger fields of view and enhanced gain.

) GWs. We theoretically identify two distinct signatures using single-dish telescopes (FAST, TMRT, QTT, GBT) and interferometers (SKA1/2-MID): transient signals from burst-like GW sources and persistent signals from cosmological background GW sources. These signatures are mapped to graviton spectral lines derived from quantum field theory by incorporating spin-2 and mass constraints, resulting in smooth, featureless profiles that are critical for distinguishing GW signals from astrophysical foregrounds. FAST attains a characteristic strain bound of hc < 10−23, approaching 10−24 in the frequency range of 1–3 GHz with a 6 hr observation period. This performance exceeds the 5σ detection thresholds for GWs originating from primordial black holes and nears the limits set by Big Bang nucleosynthesis. Additionally, projections for SKA2-MID indicate even greater sensitivity. Detecting such GWs would improve our comprehension of cosmological models, refine the parameter spaces for primordial black holes, and function as a test for quantum field theory. This approach addresses significant deficiencies in VHF GW research, improving detection sensitivity and facilitating the advancement of next-generation radio telescopes such as FASTA and Square Kilometre Array, which feature larger fields of view and enhanced gain.

Original content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 licence. Any further distribution of this work must maintain attribution to the author(s) and the title of the work, journal citation and DOI.

1. Introduction

LIGO has observed the first binary black hole gravitational-wave (GW) event (B. P. Abbott et al. 2016a, 2019a; R. Abbott et al. 2021a), heralding the beginning of GW astronomy and opening up new opportunities for cosmic exploration. GWs are expected to be detectable across the entire frequency spectrum, revealing a wide range of discoveries and exhibiting unique physical processes similar to electromagnetic waves (N. Aggarwal et al. 2021). One of the detections of extremely low-frequency GWs is planned through B-mode polarization of the cosmic microwave background (CMB) by the Ali project (H. Li et al. 2019). The very low-frequency GWs have been detected via pulsar timing arrays (R. S. Foster & D. C. Backer 1990; R. N. Manchester 2008; F. Jenet et al. 2009; M. Kramer & D. J. Champion 2013; R. N. Manchester & IPTA 2013; K. J. Lee 2016; Z. Arzoumanian et al. 2020, 2023; A. Chalumeau et al. 2022; B. Goncharov et al. 2022; K. Nobleson et al. 2022; R. Spiewak et al. 2022; G. Agazie et al. 2023; J. Antoniadis et al. 2023; R. A. Main et al. 2023; D. J. Reardon et al. 2023; A. Srivastava et al. 2023; H. Xu et al. 2023). Detections at low frequency are going to employ space-based GW interferometers (P. Amaro-Seoane et al. 2012; J. Luo et al. 2016; W.-R. Hu & Y.-L. Wu 2017; Z. Luo et al. 2020), while deci-hertz interferometer detectors are going to be utilized to detect the intermediate-frequency GWs (J. Crowder & N. J. Cornish 2005; S. Kawamura et al. 2006, 2011, 2019). And ground-based laser interferometers have been served for high-frequency detection and won the Nobel Prize (B. C. Barish & R. Weiss 1999; B. P. Abbott et al. 2009, 2018; T. Accadia et al. 2012; Y. Aso et al. 2013; J. Aasi et al. 2015; F. Acernese et al. 2015; T. Akutsu et al. 2019).

However, plans for exploration at very high frequencies (106–1012 Hz) and ultrahigh frequencies (over 1012 Hz) are presently deficient. The weakness of GW signals in these frequencies, coupled with exceedingly low photon conversion probabilities, renders detection challenging. Nonetheless, recent studies suggest potential advancements. From an observational perspective, radio telescopes (V. Domcke & C. Garcia-Cely 2021; V. Domcke 2023; N. Herman et al. 2023; V. Dandoy et al. 2024; A. Ito et al. 2024), laboratory microwave cavities (A. M. Cruise 2000; P. Bernard et al. 2001; R. Ballantini et al. 2003; F.-Y. Li et al. 2003, 2000, 2013; F.-Y. Li & N. Yang 2004; F. Li et al. 2008, 2009; M.-l. Tong et al. 2008; G. V. Stephenson 2009; J. Li et al. 2011, 2016; A. Berlin et al. 2022), X/γ-ray satellites (S. Ramazanov et al. 2023; V. Dandoy et al. 2024; T. Liu et al. 2024), and other detection methods (S. Antusch et al. 2024; L. A. Panasenko & A. O. Chetverikov 2024; W. Ratzinger et al. 2024; S. Shen et al. 2024; J. R. Valero et al. 2024; A. Barrau et al. 2025; R. Schnabel & M. Korobko 2025) are being explored as potential very high-frequency (VHF) GW detectors for the future detection. Concurrently, the theoretical origins of VHF GWs are notably abundant: the high-frequency band of the primordial GWs (M. Giovannini 1999, 2009, 2014; M. Gasperini & G. Veneziano 2003; L. P. Grishchuk 2005; M.-L. Tong & Y. Zhang 2009; A. Ito & J. Soda 2016; S. Vagnozzi & A. Loeb 2022), inflation annihilation into gravitons (J. E. Kim et al. 2005; K. N. Ananda et al. 2007; D. Baumann et al. 2007; N. Barnaby & M. Peloso 2011; L. Sorbo 2011; D. Cannone et al. 2015; M. Peloso & C. Unal 2015; N. Bartolo et al. 2016; A. Ricciardone & G. Tasinato 2017; R.-g. Cai et al. 2019), (p)reheating after inflation (S. Y. Khlebnikov & I. I. Tkachev 1997; L. Kofman et al. 1997, 1994; J. Garcia-Bellido 1998; R. Easther & E. A. Lim 2006; J. F. Dufaux et al. 2007; J. Garcia-Bellido & D. G. Figueroa 2007; J. Garcia-Bellido et al. 2008; J.-F. Dufaux et al. 2009; C. Caprini & D. G. Figueroa 2018; Y. Ema et al. 2020; B. Barman et al. 2023), Kaluza-Klein-gravitons from the braneworld scenarios (M. Servin & G. Brodin 2003; C. Clarkson & S. S. Seahra 2007; A. Nishizawa & K. Hayama 2013; D. Andriot & G. Lucena Gómez 2017), and so on. Therefore, the identification of VHF GWs holds the potential to provide us profound novel insights into the Universe, particularly the very early Universe, as GWs decouple essentially immediately after being generated (R. Roshan & G. White 2025).

In this paper, our focus is on detecting VHF GWs within the radio band 106–1011 Hz, by utilizing the inverse Gertsenshtein–Zeldovich (GZ) effect. This effect delineates the conversion of GWs into electromagnetic waves in the presence of a magnetic field (M. E. Gertsenshtein 1962; D. Boccaletti et al. 1970; W. K. De Logi & A. R. Mickelson 1977; P. G. Macedo & A. H. Nelson 1983; G. Raffelt & L. Stodolsky 1988; D. Fargion 1995; A. M. Cruise 2012; A. D. Dolgov & D. Ejlli 2012; A. Ejlli et al. 2019; D. Ejlli 2020). Strong magnetic fields convert VHF GWs into photons more significantly. Furthermore, the GZ effect is also widely applied in the research of axion–photon conversion and is used for detecting axions (A. Hook et al. 2018; U. Bhura et al. 2024; L. Walters et al. 2024). They traverse interstellar magnetic fields to our solar system, eventually reaching the radio telescope receiver. Along this trajectory, VHF GWs and their conversed photons pervade the Universe, thereby improving the quality of our observations through enhanced time-series data and heightened resolution. Our detection outcomes will provide ground-based laboratories with accessible VHF GW sources, thereby constituting collaborative observations. And, we utilize neutron stars with magnetic fields to calculate the entire conversion process and estimate the sensitivity of detecting GWs. In this work, we adopt a simplified theoretical model that assumes alignment between the neutron star’s rotational and magnetic axes, thereby neglecting the inclination angle inferred from observational measurements. This approximation is made for the purpose of an initial investigation. However, certain physical phenomena can influence the conversion probability, such as the diffraction of GWs by the neutron star. We use toy modeling in this paper to provide a brief discussion of the diffraction of GWs by the neutron star. In addition, we will examine the mechanisms that affect the conversion probability in additional articles. These mechanisms include diffraction and refraction of electromagnetic waves in the plasma surrounding the neutron star, as well as possible interference caused by speed differences between GWs and electromagnetic waves in the magnetic field.

Employing pulsars or magnetars to detect GWs of different frequencies seems to improve the observation efficiency of pulsars or magnetars. Nanohertz GWs have been found in pulsar “Fold-mode” data, and VHF GWs can be identified in baseband data due to our reliance on comprehensive electromagnetic observations around neutron stars. The observations of nanohertz and VHF GWs can be made at the same time, and the observations are not affected. In this paper, we investigate the potential of combining strong magnetic fields of celestial bodies with radio telescopes to observe VHF GWs, especially from mergers of primordial black holes (PBHs), where detection sensitivity has been significantly improved.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: In Section 2, we analyze the conversion of radio signals from GWs in the strong magnetic fields of a single neutron star and investigate the diffraction of GWs by the neutron star on the photon-specific intensity. In Section 3, we calculated the spectral line broadening of the graviton and the frequency-dependent variation of the conversed electromagnetic waves. In Section 4, we calculated the equivalent system flow and the signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) of the utilized telescope. In Section 5, we present the calculated expected GW radio signals and the detection sensitivities of six different telescopes, including the anticipated radio signals on two timescales derived from our calculations. In Section 6, we present a summary and discussion of this paper. Finally, Appendices A, B, C, and D contain essential computational procedures, unit conversions, telescope parameters, and derived results. This paper employs the natural unit system where c = ℏ = 0 = μ0 = 1.

2. Gravitational-wave Conversion Probability

In magnetic fields, GWs are converted to electromagnetic waves by the GZ effect. In this section, we will demonstrate in turn the magnitude of this conversion probability in the magnetic field of an isolated neutron star and the periodic modulation of the GW intensity caused by the GW diffraction of this neutron star, which ultimately results in the same level of periodic modulation of the electromagnetic wave conversed by the GZ effect.

2.1. Gravitational-electromagnetic Wave Mixing and Photon-specific Intensity

Now, we show the probability of converting GWs into electromagnetic waves in a typical neutron star magnetic field. In this paper, we only consider the simpler, rapidly rotating magnetic field structures. In our subsequent paper, we will simulate the entire neutron star’s magnetic field using the particle-in-cell method and refine the simulated field with current observational data (W. Hong et al. 2025). In the context of rapidly rotating magnetic fields, pulsars and magnetars can often be approximated as rotating magnetic dipoles, with the magnetic dipole axis aligned to the rotation axis, represented as  , where r0 = 10 km is the radius of neutron stars, and the magnetic dipole axis is aligned with the rotation axis

, where r0 = 10 km is the radius of neutron stars, and the magnetic dipole axis is aligned with the rotation axis  where θ represents the polar angle from the rotation and magnetic axis, and B0 is the surface magnetic field at the poles. While the Goldreich–Julian model (GJ model) was first suggested for aligned neutron stars with θm = 0, it works just as well for oblique neutron stars (P. Goldreich & W. H. Julian 1969). It gives a charge density of

where θ represents the polar angle from the rotation and magnetic axis, and B0 is the surface magnetic field at the poles. While the Goldreich–Julian model (GJ model) was first suggested for aligned neutron stars with θm = 0, it works just as well for oblique neutron stars (P. Goldreich & W. H. Julian 1969). It gives a charge density of  , where Ω is the neutron star’s spin period, and θ is its polar angle with respect to the axis of rotation. We shall use the charge density as an approximate measure of the electron number density:

, where Ω is the neutron star’s spin period, and θ is its polar angle with respect to the axis of rotation. We shall use the charge density as an approximate measure of the electron number density:  . Therefore, the plasma frequency is denoted as

. Therefore, the plasma frequency is denoted as  where

where ![${B}_{\perp }{x}_{s}=\left({B}_{0}/2\right){\left({r}_{0}/r\right)}^{3}\left[3\cos \theta {\boldsymbol{m}}\cdot {\boldsymbol{r}}-\cos {\theta }_{m}\right]$](https://content.cld.iop.org/journals/0004-637X/990/2/156/revision1/apjadf19aieqn7.gif) is the component of the magnetic field along the perpendicular direction of the traveling direction +xs of GWs, and

is the component of the magnetic field along the perpendicular direction of the traveling direction +xs of GWs, and  depends on time due to the rotation of the neutron stars. As we only consider the cold plasma scenario in order to simplify the model, relativistic effects on the plasma frequency correction are not relevant. Electromagnetic wave propagation in plasma is based on the premise that the frequency of the electromagnetic wave is higher than that of the plasma. This allows us to calculate the minimum spatial scale of the inverse GZ effect occurring radially using the formula

depends on time due to the rotation of the neutron stars. As we only consider the cold plasma scenario in order to simplify the model, relativistic effects on the plasma frequency correction are not relevant. Electromagnetic wave propagation in plasma is based on the premise that the frequency of the electromagnetic wave is higher than that of the plasma. This allows us to calculate the minimum spatial scale of the inverse GZ effect occurring radially using the formula

It is important to note that, when the GW frequency is higher, the calculated result of roccur will be less than the radius of the neutron star r0, which is not physical. Therefore, when the calculated result of roccur is less than the neutron star radius r0, we fix roccur to r0 = 10 km. Obviously, when the radius is greater than roccurs, the GZ effect still exists, but the conversion probability decreases as the neutron star’s magnetic field strength decreases.

GWs are converted into photons in neutron stars’ magnetic fields. However, some neutron stars’ magnetic fields are stronger than the critical magnetic field  (D. Lai & E. E. Salpeter 1995; D. Lai 2001), which will lead to some additional physical processes, where ∣qf∣ denotes the elementary charge. In the presence of an external field, the interaction of observables must be analyzed due to the resummation of higher-order diagrams, leading to nonlinear dependencies known as “nonlinear QED.” Within the frequency range of 106–1011 Hz, the photon’s wavelength is λγ ≈ 3 × 10−4–300 m, which is much larger than the electron’s Compton wavelength:

(D. Lai & E. E. Salpeter 1995; D. Lai 2001), which will lead to some additional physical processes, where ∣qf∣ denotes the elementary charge. In the presence of an external field, the interaction of observables must be analyzed due to the resummation of higher-order diagrams, leading to nonlinear dependencies known as “nonlinear QED.” Within the frequency range of 106–1011 Hz, the photon’s wavelength is λγ ≈ 3 × 10−4–300 m, which is much larger than the electron’s Compton wavelength:  . Additionally, their energy Eγ ≈ 10−10–10−5 eV, significantly smaller than the electron’s mass me = 0.511 MeV, thereby validating the Heisenberg–Euler effective Lagrangian (W. Heisenberg & H. Euler 1936; J. S. Schwinger 1951). Consequently, the action of GW–photon conversion within the proper time integral is (S. L. Adler 1971; W.-y. Tsai 1974; W.-y. Tsai & T. Erber 1974, 1975; D. B. Melrose & R. J. Stoneham 1976; L. F. Urrutia 1978; W. Dittrich & M. Reuter 1985; W. Dittrich & H. Gies 2000)

. Additionally, their energy Eγ ≈ 10−10–10−5 eV, significantly smaller than the electron’s mass me = 0.511 MeV, thereby validating the Heisenberg–Euler effective Lagrangian (W. Heisenberg & H. Euler 1936; J. S. Schwinger 1951). Consequently, the action of GW–photon conversion within the proper time integral is (S. L. Adler 1971; W.-y. Tsai 1974; W.-y. Tsai & T. Erber 1974, 1975; D. B. Melrose & R. J. Stoneham 1976; L. F. Urrutia 1978; W. Dittrich & M. Reuter 1985; W. Dittrich & H. Gies 2000)

where R represents the Ricci scalar, and g denotes the determinant of the metric gμν. The effective Lagrangian is given by Leff = L(0) + L(1), where  is the original Maxwell Lagrangian, and L(1) is equal to

is the original Maxwell Lagrangian, and L(1) is equal to ![$\frac{i{m}_{e}^{4}}{2{\hslash }^{3}}{\int }_{0}^{\infty }\frac{d\tau }{\tau }{{\rm{e}}}^{-\epsilon \tau }{{\rm{e}}}^{-i\tau {m}_{e}^{2}}{\rm{tr}}\left[\left\langle x\left|{{\rm{e}}}^{-i\hat{H}\tau }\right|x\right\rangle -\left\langle x\left|{{\rm{e}}}^{-i{\hat{H}}_{0}\tau }\right|x\right\rangle \right]$](https://content.cld.iop.org/journals/0004-637X/990/2/156/revision1/apjadf19aieqn12.gif) , and represents the effective action for the gauge field Aμ. In

, and represents the effective action for the gauge field Aμ. In  , τ represents the proper time,

, τ represents the proper time, > 0 is an infinitesimal parameter used for the resum of the effective action, tr signifies the remaining trace over the Dirac spinor space, and

denotes the Hamiltonian. Dμ =∂μ + iqf Aμ(x),

denotes the Hamiltonian. Dμ =∂μ + iqf Aμ(x), ![${\sigma }_{\mu \nu }=i/2\left[{\gamma }_{\mu },{\gamma }_{\nu }\right]$](https://content.cld.iop.org/journals/0004-637X/990/2/156/revision1/apjadf19aieqn15.gif) , and

, and  indicates the free Hamiltonian (W.-y. Tsai & T. Erber 1974, 1975; K. Hattori & K. Itakura 2013a, 2013b). Under the one-loop effective action assumption and the Bianchi identity with the relation

indicates the free Hamiltonian (W.-y. Tsai & T. Erber 1974, 1975; K. Hattori & K. Itakura 2013a, 2013b). Under the one-loop effective action assumption and the Bianchi identity with the relation  , we can expand the Lagrangian L(1) to the first order in the form with the heat-kernel method

, we can expand the Lagrangian L(1) to the first order in the form with the heat-kernel method  , where the

, where the  ’s denote local functions of the field strength tensor Fμν, and the background gauge is assumed (V. P. Gusynin & I. A. Shovkovy1996, 1999; D. V. Vassilevich 2003). Moreover, the two Lorentz invariants of a mass-dimension of four are

’s denote local functions of the field strength tensor Fμν, and the background gauge is assumed (V. P. Gusynin & I. A. Shovkovy1996, 1999; D. V. Vassilevich 2003). Moreover, the two Lorentz invariants of a mass-dimension of four are  and

and  . Then, the remaining trace term in L(1) can be obtained as

. Then, the remaining trace term in L(1) can be obtained as ![$\frac{{ \mathcal G }}{4{\pi }^{2}}\cot \left(\tau {f}_{1}\right)\cot \left(\tau {f}_{2}\right)\left[1+{{ \mathcal H }}^{\mu \nu }+\cdots \,\right]$](https://content.cld.iop.org/journals/0004-637X/990/2/156/revision1/apjadf19aieqn22.gif) , where

, where  is

is ![${F}^{i}{F}_{\mu }{F}^{j}{F}_{\nu }{F}^{k}{Y}_{1}^{ijk}+{F}^{i}{F}_{\nu }{F}^{j}{F}_{\mu }{Y}_{2}^{ijk}+{F}^{i}{\rm{tr}}\left[{F}_{\mu }^{* }{F}_{v}{F}^{j}\right]{Y}_{3}^{ij}$](https://content.cld.iop.org/journals/0004-637X/990/2/156/revision1/apjadf19aieqn24.gif) . In the term

. In the term  , Fλ denotes the matrix form of the tensor ∇λFμν,

, Fλ denotes the matrix form of the tensor ∇λFμν,  and

and  are functions of

are functions of  ,

,  , and τ, and a summation over i, j, and k is assumed. Finally, we can express the gauge potential in terms of the electromagnetic fields from the field strength tensor as

, and τ, and a summation over i, j, and k is assumed. Finally, we can express the gauge potential in terms of the electromagnetic fields from the field strength tensor as

. Combining with the electrodynamics equations in curved spacetime, we can calculate the linearized equations of motion for GWs and photons (D. Boccaletti et al. 1970). At the same time, some enlightening calculations of the GZ effect can also be referred to in these papers that discuss the conversion of axions into photons (A. Hook et al. 2018; U. Bhura et al. 2024; L. Walters et al. 2024).

. Combining with the electrodynamics equations in curved spacetime, we can calculate the linearized equations of motion for GWs and photons (D. Boccaletti et al. 1970). At the same time, some enlightening calculations of the GZ effect can also be referred to in these papers that discuss the conversion of axions into photons (A. Hook et al. 2018; U. Bhura et al. 2024; L. Walters et al. 2024).

Given that the inverse GZ effect is most pronounced when the direction of the magnetic field is perpendicular to the direction of the GW propagation, as is well known, GWs can be expressed with the traceless transverse gauge, which means h0i = 0, ∂jhij = 0, and  . The Euler–Lagrange equations of motion from the Heisenberg–Euler effective Lagrangian (2) for the propagating photon and graviton fields components, Aμ and hij propagating in the external magnetic field, are generally read as ∇2A0 = 0,

. The Euler–Lagrange equations of motion from the Heisenberg–Euler effective Lagrangian (2) for the propagating photon and graviton fields components, Aμ and hij propagating in the external magnetic field, are generally read as ∇2A0 = 0, ![${{\boldsymbol{A}}}^{i}-{L}^{(1)}+{\partial }^{i}{\partial }_{\mu }{A}^{\mu }=\sqrt{16\pi G}{\partial }_{\mu }\left[{h}^{\mu \beta }{F}_{\beta }^{i}-{h}^{i\beta }{F}_{\beta }^{\mu }\right]$](https://content.cld.iop.org/journals/0004-637X/990/2/156/revision1/apjadf19aieqn34.gif) , and

, and  . When we consider the case where GWs pass through the rotational axis, the above equation can be further simplified. The linearized equations of motion for GWs and photons propagating along the direction xs, perpendicular to the background magnetic field, are derived as follows as the Coulomb gauge condition makes ∂iAi = 0, and we can also choose A0 = 0 (G. Raffelt & L. Stodolsky 1988; M. Maggiore 2000; A. D. Dolgov & D. Ejlli 2012),

. When we consider the case where GWs pass through the rotational axis, the above equation can be further simplified. The linearized equations of motion for GWs and photons propagating along the direction xs, perpendicular to the background magnetic field, are derived as follows as the Coulomb gauge condition makes ∂iAi = 0, and we can also choose A0 = 0 (G. Raffelt & L. Stodolsky 1988; M. Maggiore 2000; A. D. Dolgov & D. Ejlli 2012),

where TT means transverse and traceless, so  and

and  , similar to the vector potential Ai. The total frequency term

, similar to the vector potential Ai. The total frequency term  involves the plasma and QED effect frequencies (W. Heisenberg & H. Euler 1936; L. D. Landau & E. M. Lifshitz 1960; S. L. Adler 1971; C. Itzykson & J. B. Zuber 1980). Moreover, we also consider the cyclotron frequency ωcyc within magnetar. In this paper, we consider cold plasma, and its frequency is

involves the plasma and QED effect frequencies (W. Heisenberg & H. Euler 1936; L. D. Landau & E. M. Lifshitz 1960; S. L. Adler 1971; C. Itzykson & J. B. Zuber 1980). Moreover, we also consider the cyclotron frequency ωcyc within magnetar. In this paper, we consider cold plasma, and its frequency is  where

where  is the fine structure constant, and ne is the electron number density. It is worth noting that the frequency of photons ωγ needs to be greater than the plasma frequency ωplasma to propagate in the plasma, indicating a minimum detectable frequency ωGW > ωplasma. The QED effect frequency is derived from the vacuum polarization tensor and corresponds to the refractive indices. For an ordinary magnetic field, the QED effect frequencies are

is the fine structure constant, and ne is the electron number density. It is worth noting that the frequency of photons ωγ needs to be greater than the plasma frequency ωplasma to propagate in the plasma, indicating a minimum detectable frequency ωGW > ωplasma. The QED effect frequency is derived from the vacuum polarization tensor and corresponds to the refractive indices. For an ordinary magnetic field, the QED effect frequencies are  , and

, and  . For a strong magnetic field whose B > Bcritical, the Coulomb force on electrons is a small perturbation compared to the magnetic force (D. Lai 2001). Therefore, we calculate the QED effect frequency under a wrenchless field state with a pure magnetic field (J. S. Heyl & L. Hernquist 1997a, 1997b; G. V. Dunne 2004; J. O. Andersen et al. 2016). These frequencies are denoted as

. For a strong magnetic field whose B > Bcritical, the Coulomb force on electrons is a small perturbation compared to the magnetic force (D. Lai 2001). Therefore, we calculate the QED effect frequency under a wrenchless field state with a pure magnetic field (J. S. Heyl & L. Hernquist 1997a, 1997b; G. V. Dunne 2004; J. O. Andersen et al. 2016). These frequencies are denoted as  and

and  , where

, where

,

,  , ρ = Bcritical/∣B∣, and ζ(z, a) =

, ρ = Bcritical/∣B∣, and ζ(z, a) =  is the Hurwitz zeta function (E. Elizalde 1986; see also a brief description in Appendix A). It is worth noting that, for weaker magnetic fields and lower detection frequencies, it is calculated that the QED effect can be ignored. But with an increase of magnetic field intensity and detection frequency, the QED effect gradually becomes significant. In the analysis of the inhomogeneous wave equation system (Equation (3)), one can typically determine the eigenmodes of the associated homogeneous problem by employing the method of separation of variables in conjunction with Duhamel’s principle. Accordingly, we first assume that the photon propagates a short distance s along the +xs direction, which is perpendicular to the background magnetic field. Under this assumption, the magnetic field within this region can be regarded as slowly varying and nearly uniform. That is, the temporal variation of the neutron star’s magnetic field at this short distance is much slower than the characteristic frequency of the photon. The solution of Equation (3) with a single frequency mode ω can be expressed as

is the Hurwitz zeta function (E. Elizalde 1986; see also a brief description in Appendix A). It is worth noting that, for weaker magnetic fields and lower detection frequencies, it is calculated that the QED effect can be ignored. But with an increase of magnetic field intensity and detection frequency, the QED effect gradually becomes significant. In the analysis of the inhomogeneous wave equation system (Equation (3)), one can typically determine the eigenmodes of the associated homogeneous problem by employing the method of separation of variables in conjunction with Duhamel’s principle. Accordingly, we first assume that the photon propagates a short distance s along the +xs direction, which is perpendicular to the background magnetic field. Under this assumption, the magnetic field within this region can be regarded as slowly varying and nearly uniform. That is, the temporal variation of the neutron star’s magnetic field at this short distance is much slower than the characteristic frequency of the photon. The solution of Equation (3) with a single frequency mode ω can be expressed as  where λ = × and +. Hence, Equation (3) is restated as

where λ = × and +. Hence, Equation (3) is restated as

where  is the mixing mass matrix (G. Raffelt & L. Stodolsky 1988; D. Ejlli 2020; V. Domcke & C. Garcia-Cely 2021; T. Liu et al. 2024)

is the mixing mass matrix (G. Raffelt & L. Stodolsky 1988; D. Ejlli 2020; V. Domcke & C. Garcia-Cely 2021; T. Liu et al. 2024)

where Beff represents the effective magnetic field strength related to the magnetic field distribution at the local level. Similar to the WKB limit (G. Wentzel 1926; C. Eckart 1948), Equation (4) is reduced to a linearized system  with

with ![$\left[\omega -i{\partial }_{s}+{m}_{j}\right]{\psi }_{j}=0$](https://content.cld.iop.org/journals/0004-637X/990/2/156/revision1/apjadf19aieqn52.gif) for j = 1, 2. This system yields an exact solution

for j = 1, 2. This system yields an exact solution  , where mj represents the eigenvalue of

, where mj represents the eigenvalue of  , and U denotes the eigenvector matrix that is associated with the scattering cross section from the particle collider. Then, the GW–photon conversion process is obtained by solving

, and U denotes the eigenvector matrix that is associated with the scattering cross section from the particle collider. Then, the GW–photon conversion process is obtained by solving  with the condition

with the condition  , so

, so

where ![$\hat{\theta }(s)=\arctan \left[\tan \left(\frac{{m}_{1}+{m}_{2}}{2}s\right)+\pi \right]$](https://content.cld.iop.org/journals/0004-637X/990/2/156/revision1/apjadf19aieqn57.gif) .

.

Furthermore, the distance over which GWs propagate through the magnetosphere of a neutron star is evidently much larger than the infinitesimal displacement s, rendering the approximation of a homogeneous magnetic field invalid. The spatial inhomogeneities in both the magnetic field and the electron density lead to position-dependent coefficients in the wave equation, necessitating a perturbative treatment of Equation (3). This can be achieved by transforming to the interaction picture via  , allowing the full solution to be systematically constructed through iterative expansion from an usual iteration. In practice, a first-order approximation using the distorted wave function approach proves sufficient, wherein conversion probabilities between regions of locally homogeneous magnetic field and electron density are incorporated. Finally, the probability that a GW with the frequency ω traveling a distance L at the polar angle θ of a neutron star is converted into photons is

, allowing the full solution to be systematically constructed through iterative expansion from an usual iteration. In practice, a first-order approximation using the distorted wave function approach proves sufficient, wherein conversion probabilities between regions of locally homogeneous magnetic field and electron density are incorporated. Finally, the probability that a GW with the frequency ω traveling a distance L at the polar angle θ of a neutron star is converted into photons is

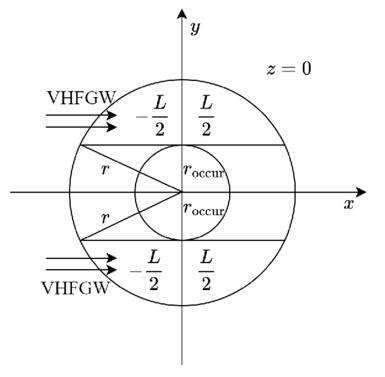

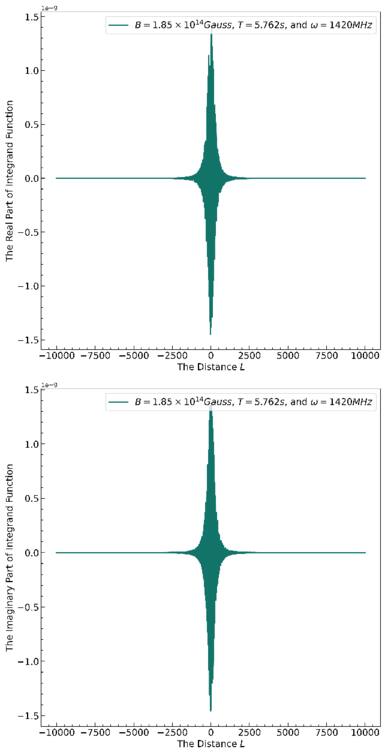

For readability, please refer to Appendix C for the detailed calculation of Equation (7); Figure 16 shows the variation of the real and imaginary parts of this integral with the traversal distance L. In theory, the typical distance L should be influenced by the absorption and scattering of matter in the magnetic field. However, given that the interaction cross section of gravitons is  with the four-dimensional Planck length lp (S. Boughn & T. Rothman 2006; A. Palessandro & M. S. Sloth 2020), and this value is generally unaffected by the internal structure of gravitons (R. F. Sawyer 2020), coupled with the absence of extreme gravitational objects like black holes in our observation path, we infer that the absorption and scattering coefficients of gravitons are minimal and can be disregarded. Therefore, the distance L is solely determined by the graviton’s energy and the intensity, orientation, and magnitude of the magnetic field. Moreover, due to the absorption and scattering effects of the medium on photons, the conversion probability from a single GW to a photon is not equivalent to the conversion probability from a single photon to a GW. So we need to calculate the length of this typical distance L. In Figure 1, we show the minimum radius roccur at which GWs cross the magnetar equator and radio-observable converted photons. Starting with the simplest, we can now determine the conversion probability of neutron stars for a particular path at the location of roccur at their equators θ = 0.

with the four-dimensional Planck length lp (S. Boughn & T. Rothman 2006; A. Palessandro & M. S. Sloth 2020), and this value is generally unaffected by the internal structure of gravitons (R. F. Sawyer 2020), coupled with the absence of extreme gravitational objects like black holes in our observation path, we infer that the absorption and scattering coefficients of gravitons are minimal and can be disregarded. Therefore, the distance L is solely determined by the graviton’s energy and the intensity, orientation, and magnitude of the magnetic field. Moreover, due to the absorption and scattering effects of the medium on photons, the conversion probability from a single GW to a photon is not equivalent to the conversion probability from a single photon to a GW. So we need to calculate the length of this typical distance L. In Figure 1, we show the minimum radius roccur at which GWs cross the magnetar equator and radio-observable converted photons. Starting with the simplest, we can now determine the conversion probability of neutron stars for a particular path at the location of roccur at their equators θ = 0.

Figure 1. The top view illustrates the movement of GWs across a magnetar or pulsar equator in three-dimensional coordinates.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageFor electromagnetic waves traveling through plasma, the propagation speed of the wave energy is described as the group velocity  . Obviously, in the neutron star magnetosphere, the speed of the GW and the generated electromagnetic wave are not consistent, so the electromagnetic wave generated by the GZ effect will cause interference in the path of the GW. Instead of calculating complex interference phenomena, we can turn to calculating the coherence lengths Lcoherence of electromagnetic waves in different regions of the neutron star’s magnetic field (D. Fargion 1995)

. Obviously, in the neutron star magnetosphere, the speed of the GW and the generated electromagnetic wave are not consistent, so the electromagnetic wave generated by the GZ effect will cause interference in the path of the GW. Instead of calculating complex interference phenomena, we can turn to calculating the coherence lengths Lcoherence of electromagnetic waves in different regions of the neutron star’s magnetic field (D. Fargion 1995)

In the magnetosphere and the surrounding magnetic field of a neutron star, the coherence length Lcoherence is always significantly smaller than the travel distance L of the GW. Therefore, in the travel distance of GWs with the length L, the conversion probability  considering the electromagnetic wave interference phenomenon can be approximated by the total number of coherent domains ηcoherence = L/Lcoherence and the conversion probability Pg→γ(L, ω, θ) without considering interference conditions

considering the electromagnetic wave interference phenomenon can be approximated by the total number of coherent domains ηcoherence = L/Lcoherence and the conversion probability Pg→γ(L, ω, θ) without considering interference conditions

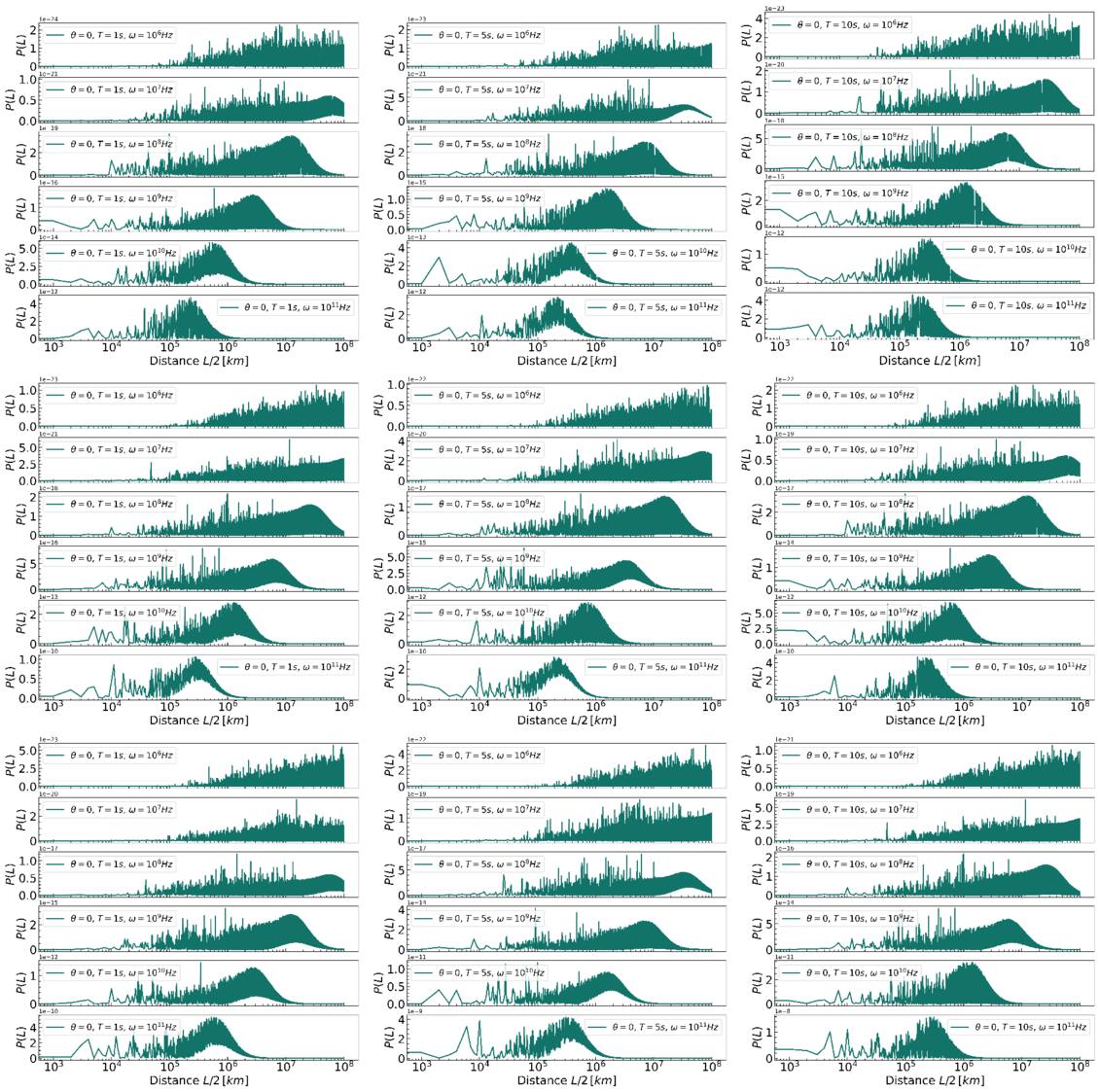

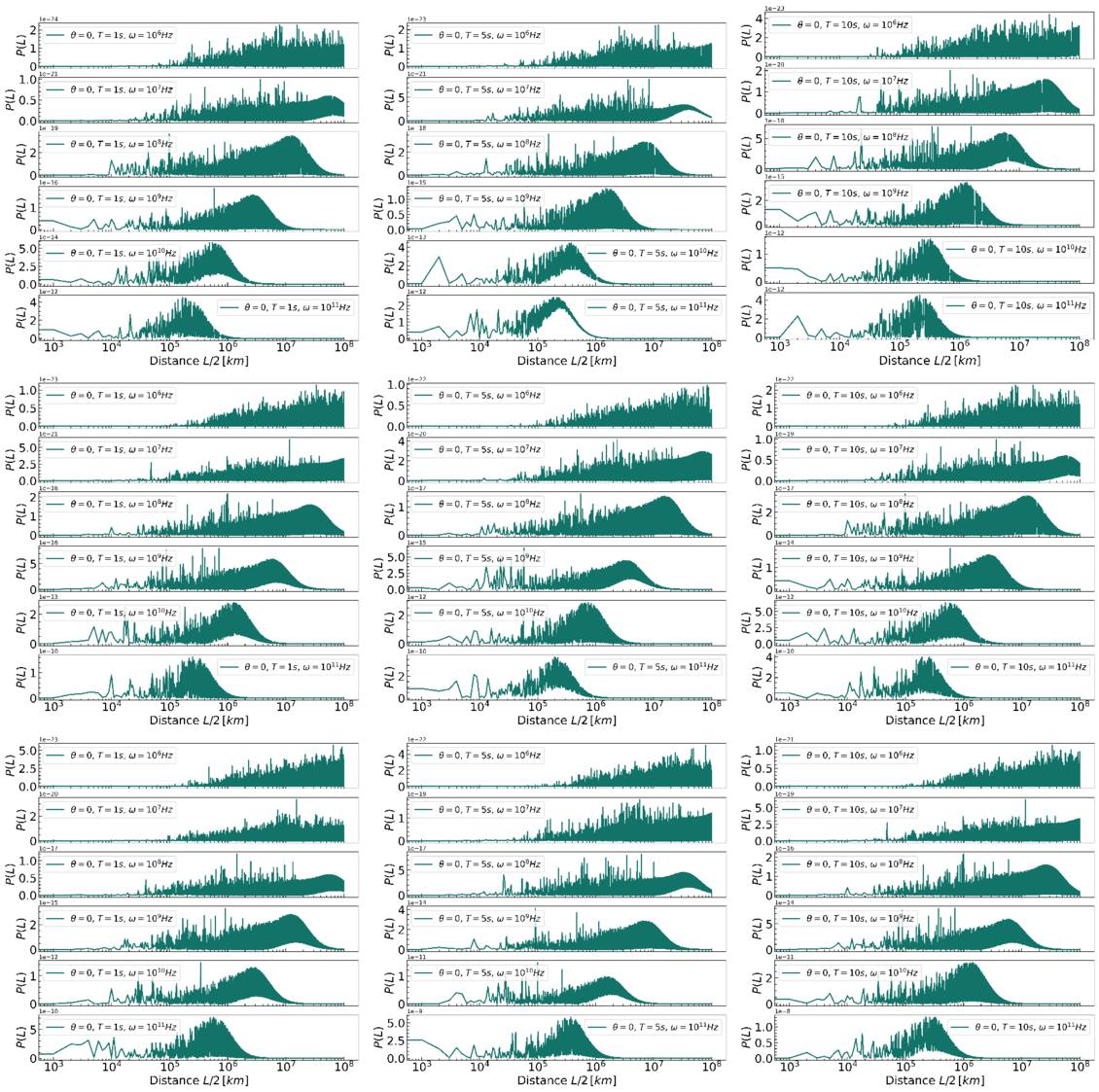

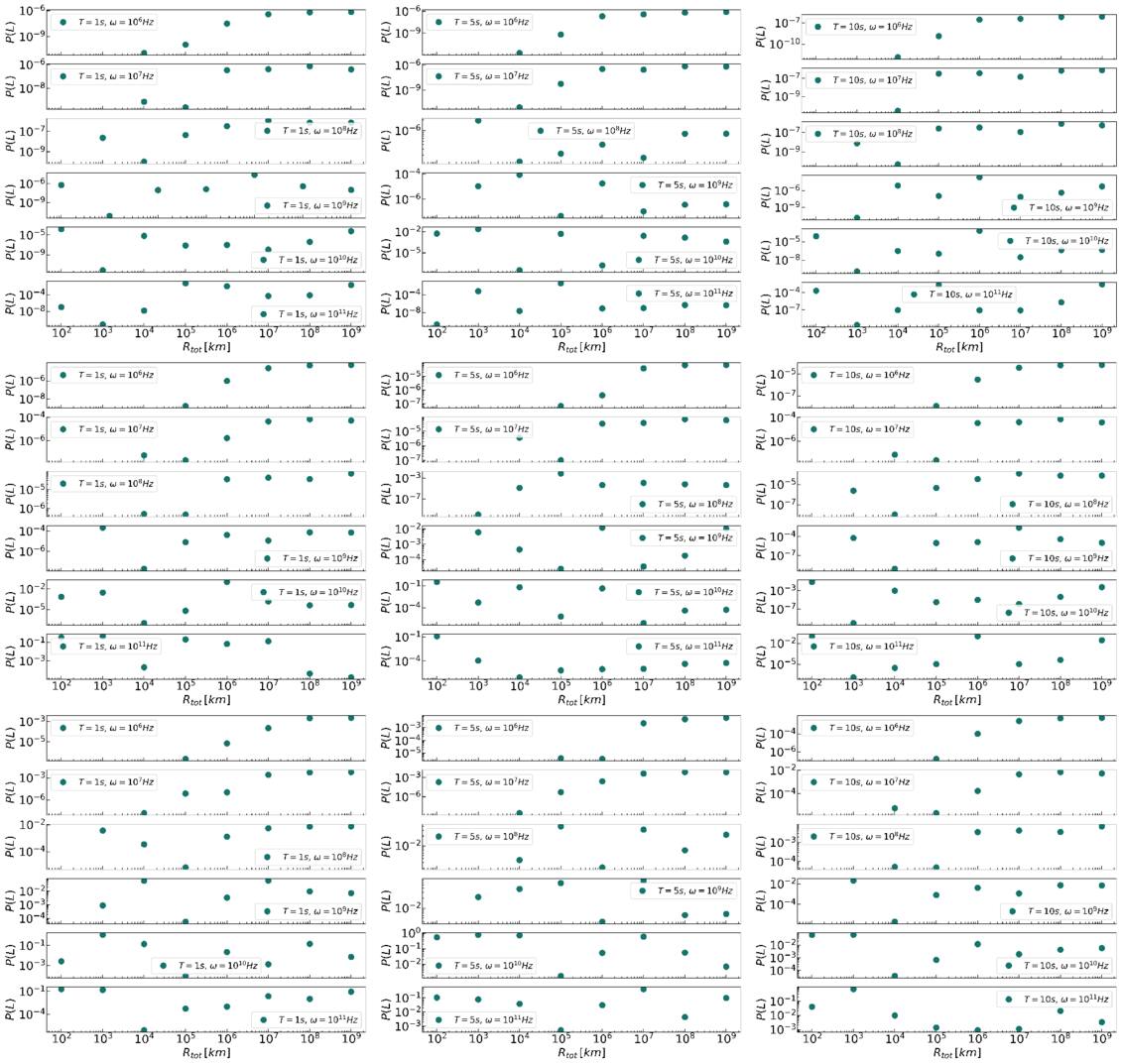

To estimate the order of magnitude of the conversion probability  for a single GW traveling along the equator, we preselected neutron star data from the ATNF Pulsar Catalog (R. N. Manchester et al. 2005; A. Staff 2005) and the McGill Online Magnetar Catalog (S. A. Olausen & V. M. Kaspi 2014; M. Staff 2014). They are listed in Table 1. Our selection of these pulsars or magnetars is based on the distance of the neutron stars and the strength of the magnetic field. Estimating the order of magnitude of the conversion probability can be divided into two steps. First, we use this table to select neutron stars with magnetic fields Beff of 1015 Gauss, 1014 Gauss, 1013 Gauss, spin periods P of 10, 5, and 1 s, and distances of 2, 1, and 0.5 kpc. We then use the information to calculate the radio signal conversed by GWs in the neutron star’s magnetic field along this path and the simple radiation mechanism. We have categorized the results of our calculations into a cross polarization and plus-polarization of conversion probability, as fully shown in Figures 17 and 18, respectively, in Appendix D for readability, and only shown in one diagram for comparison in Figure 2. Meanwhile, under identical parameter settings, we computed the conversion probabilities of GWs at various deflection angles at the radius r = roccur of the neutron star. The calculation results for various frequencies are presented in Figure 3. Figure 3 illustrates that the conversion probability exhibits periodic variation in relation to the magnetic field distribution of neutron stars.

for a single GW traveling along the equator, we preselected neutron star data from the ATNF Pulsar Catalog (R. N. Manchester et al. 2005; A. Staff 2005) and the McGill Online Magnetar Catalog (S. A. Olausen & V. M. Kaspi 2014; M. Staff 2014). They are listed in Table 1. Our selection of these pulsars or magnetars is based on the distance of the neutron stars and the strength of the magnetic field. Estimating the order of magnitude of the conversion probability can be divided into two steps. First, we use this table to select neutron stars with magnetic fields Beff of 1015 Gauss, 1014 Gauss, 1013 Gauss, spin periods P of 10, 5, and 1 s, and distances of 2, 1, and 0.5 kpc. We then use the information to calculate the radio signal conversed by GWs in the neutron star’s magnetic field along this path and the simple radiation mechanism. We have categorized the results of our calculations into a cross polarization and plus-polarization of conversion probability, as fully shown in Figures 17 and 18, respectively, in Appendix D for readability, and only shown in one diagram for comparison in Figure 2. Meanwhile, under identical parameter settings, we computed the conversion probabilities of GWs at various deflection angles at the radius r = roccur of the neutron star. The calculation results for various frequencies are presented in Figure 3. Figure 3 illustrates that the conversion probability exhibits periodic variation in relation to the magnetic field distribution of neutron stars.

Table 1. The List of Typical Neutron Stars for Estimation of the Order of Magnitude of the Conversion Probability in This Paper

| Pulsar Name | R.A. | Decl. | Barycentric | Pulsar | Surface Magnetic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J2000 | J2000 | J2000 | Period | Distance | Flux Density |

| (hh:mm:ss.s) | (+dd:mm:ss) | (s) | (kpc) | (Gauss) | |

| PSR J1808-2024 | 18:08:39.337 | −20:24:39.85 | 7.55592 | 13.000 | 2.06e+15 |

| PSR J0501+4516 | 05:01:06.76 | +45:16:33.92 | 5.76209653 | 2.000 | 1.85e+14 |

| PSR J1809-1943 | 18:09:51.08696 | −19:43:51.9315 | 5.540742829 | 3.600 | 1.27e+14 |

| PSR J1550-5418 | 15:50:54.12386 | −54:18:24.1141 | 2.06983302 | 4.000 | 2.22e+14 |

| PSR J0736-6304 | 07:36:20.01 | −63:04:16 | 4.8628739612 | 0.104 | 2.75e+13 |

| PSR J1856-3754 | 18:56:35.41 | −37:54:35.8 | 7.05520287 | 0.160 | 1.47e+13 |

| PSR J0720-3125 | 07:20:24.9620 | −31:25:50.083 | 8.391115532 | 0.400 | 2.45e+13 |

| PSR J1740-3015 | 17:40:33.82 | −30:15:43.5 | 0.60688662425 | 0.400 | 1.7e+13 |

| PSR J1731-4744 | 17:31:42.160 | −47:44:36.26 | 0.82982878524 | 0.700 | 1.18e+13 |

| PSR J1848-1952 | 18:48:18.03 | −19:52:31 | 4.30818959857 | 0.751 | 1.01e+13 |

| SGR J0501+4516 | 05:01:06.76 | +45:16:33.92 | 5.7620695 | 2 | 1.9e+14 |

| SGR J0418+5729 | 04:18:33.867 | +57:32:22.91 | 9.07838822 | 2 | 6.1e+12 |

| SGR J1935+2154 | 19:34:55.598 | +21:53:47.79 | 3.2450650 | ⋯ | 2.2e+14 |

References (C. Kouveliotou et al. 1998) (E. Gogus et al. 2008) (A. I. Ibrahim et al. 2004) (F. Camilo et al. 2007) (S. Burke-Spolaor & M. Bailes 2010) (A. Tiengo & S. Mereghetti 2007) (F. Haberl et al. 1997) (T. R. Clifton & A. G. Lyne 1986) (M. I. Large et al. 1968) (R. N. Manchester et al. 1978) (A. Camero et al. 2014) (N. Rea et al. 2013) (G. L. Israel et al. 2016).

Download table as: ASCIITypeset image

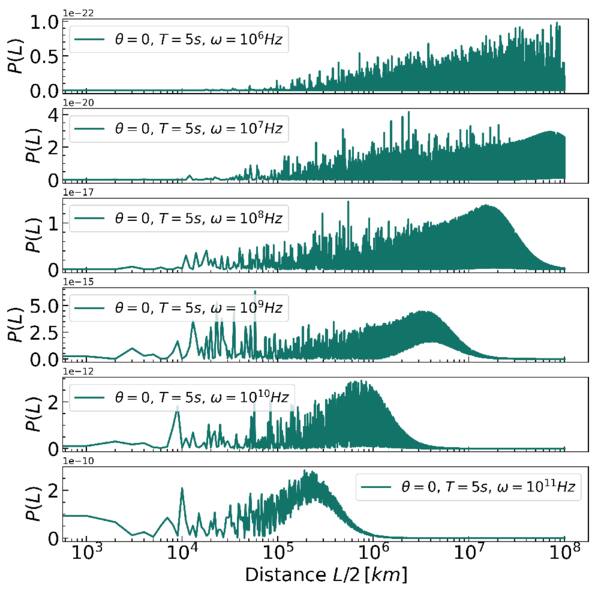

Figure 2. The conversion probability  pertains to the cross polarization (“×”-polarization) of gravitational waves as they traverse varying distances within a neutron star’s magnetic field. The assumed parameters of the magnetic field are B = 1014 Gauss and

pertains to the cross polarization (“×”-polarization) of gravitational waves as they traverse varying distances within a neutron star’s magnetic field. The assumed parameters of the magnetic field are B = 1014 Gauss and  . The panel illustrates, from top to bottom, the outcome of a tenfold increase in the frequency of the radio telescope over time, alongside a gradual increase in the overall conversion probability. Simultaneously, it is evident that, as frequency increases, the location of the maximum conversion probability shifts closer to the neutron star radius.

. The panel illustrates, from top to bottom, the outcome of a tenfold increase in the frequency of the radio telescope over time, alongside a gradual increase in the overall conversion probability. Simultaneously, it is evident that, as frequency increases, the location of the maximum conversion probability shifts closer to the neutron star radius.

Download figure:

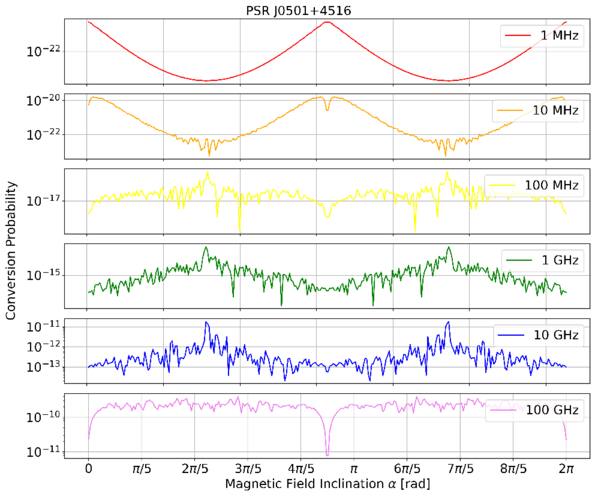

Standard image High-resolution imageFigure 3. The conversion probability  pertains to the cross polarization (“×”-polarization) of gravitational waves as they traverse varying inclinations within a neutron star’s magnetic field. The assumed parameters of the magnetic field are B = 1014 Gauss and

pertains to the cross polarization (“×”-polarization) of gravitational waves as they traverse varying inclinations within a neutron star’s magnetic field. The assumed parameters of the magnetic field are B = 1014 Gauss and  . The panel illustrates, from top to bottom, the outcome of a tenfold increase in the frequency of the radio telescope over a specific period, revealing a clear periodic variation in the conversion probability.

. The panel illustrates, from top to bottom, the outcome of a tenfold increase in the frequency of the radio telescope over a specific period, revealing a clear periodic variation in the conversion probability.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageBecause of the space-accumulation effect of the GZ effect and the change in the magnetar’s magnetic field’s direction, we can see from the two figures that the conversion probability first rises and then falls as the GW passes through the magnetar for a specific distance (F.-Y. Li et al. 2020). These two figures also show that the distance with the highest probability of GW–photon conversion is between ∼106 and ∼108 km when the frequency of the GW is between 106 and 1011 Hz. This distance exceeds the radius of a neutron star’s light cylinder, which is RLC = cP/2π ≃ 5 × 109 cmP0 (Y.-P. Yang et al. 2020). Additionally, as the magnetar’s spin period and GW frequency increase, this distance gets smaller. It is important to note that some of the finer magnetic field structures in the neutron star magnetosphere cannot be reflected in the simple estimate because we consider the aligned GJ model in this paper. This is the main estimate we will do in the next paper and is highly worthy of further investigation.

As aforementioned, the determination of the specific intensity of the converted photon Iγ,ω at the frequency ω relies on the total conversion rate  (G. Raffelt & L. Stodolsky 1988), denoting the integrated conversion probability per unit of time and solid angle, alongside the VHF GW’s differential energy fraction ΩGW(ω). Considering the radio telescope’s frequency binning

(G. Raffelt & L. Stodolsky 1988), denoting the integrated conversion probability per unit of time and solid angle, alongside the VHF GW’s differential energy fraction ΩGW(ω). Considering the radio telescope’s frequency binning  , the final specific intensity generated in the magnetic field can be expressed as

, the final specific intensity generated in the magnetic field can be expressed as

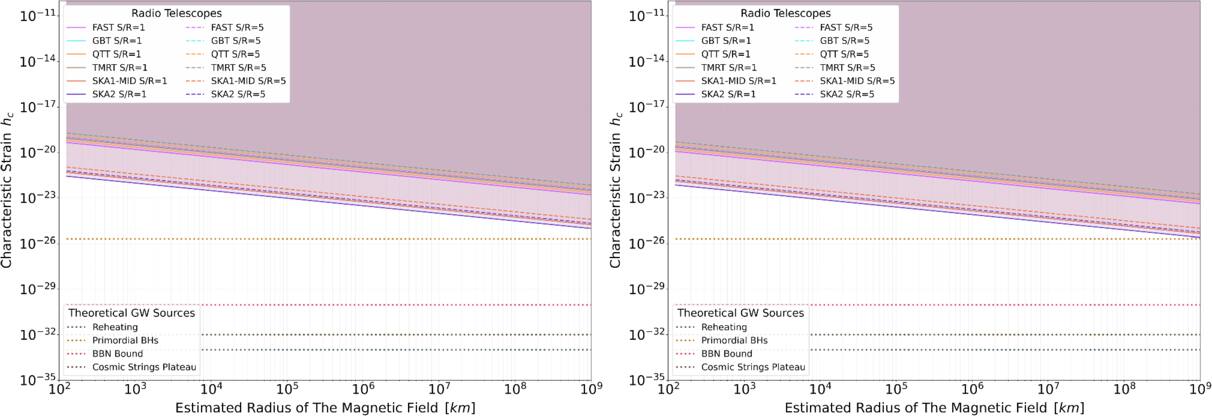

where H0 is the Hubble constant (Planck Collaboration et al. 2020a), and  represents the reduced Planck mass. Now, let us determine the magnitude of this solid angle Δθ. Considering a neutron star with a distance d from us, the region where the VHF GWs are converted into photons is spherical and has a radius of Rtot. This radius Rtot can be a local point of the neutron star’s magnetic field, a region, or the entire magnetic field. The size and choice of this radius will greatly affect the size of the final conversion probability. To determine the size of a Rtot, it is most convenient and optimistic to analyze an integral region of infinite size. This allows for the calculation of the maximum conversion probability and the optimal utilization of the telescope’s field of view. However, this is actually not a rational assumption. When the region is of considerable size, the magnetic field of the neutron star will weaken significantly, eventually being superseded by other magnetic fields in astrophysics. Consequently, we can no longer solely attribute the observational effect we are currently investigating to the neutron star. Hence, two factors influence the magnitude of a signal’s field of view: First, the strength of the magnetic field must be higher than the average magnetic field of the Universe B0 ≲ 47 pGauss, which allows the magnetic field region to extend to a radius of up to 109 km (A. Neronov & I. Vovk 2010; F. Tavecchio et al. 2010; R. Durrer & A. Neronov 2013; K. Takahashi et al. 2013; P. A. R. Ade et al. 2016; M. S. Pshirkov et al. 2016; K. Jedamzik & A. Saveliev 2019; V. Domcke & C. Garcia-Cely 2021). Second, it is evident that the signal’s effective field of vision cannot surpass the telescope’s field of view (see our discussion of this in Appendix B). Therefore, we can consider the following simple model: The telescope is centered on a neutron star, and the data at the back end of the observation are actually the integrated total voltage of all radio signals across the telescope’s field of view (A. R. Thompson et al. 2017). It is clear that Rtot is greater than roccur for actual observation. Therefore, we can determine the total energy flux reaching Earth

represents the reduced Planck mass. Now, let us determine the magnitude of this solid angle Δθ. Considering a neutron star with a distance d from us, the region where the VHF GWs are converted into photons is spherical and has a radius of Rtot. This radius Rtot can be a local point of the neutron star’s magnetic field, a region, or the entire magnetic field. The size and choice of this radius will greatly affect the size of the final conversion probability. To determine the size of a Rtot, it is most convenient and optimistic to analyze an integral region of infinite size. This allows for the calculation of the maximum conversion probability and the optimal utilization of the telescope’s field of view. However, this is actually not a rational assumption. When the region is of considerable size, the magnetic field of the neutron star will weaken significantly, eventually being superseded by other magnetic fields in astrophysics. Consequently, we can no longer solely attribute the observational effect we are currently investigating to the neutron star. Hence, two factors influence the magnitude of a signal’s field of view: First, the strength of the magnetic field must be higher than the average magnetic field of the Universe B0 ≲ 47 pGauss, which allows the magnetic field region to extend to a radius of up to 109 km (A. Neronov & I. Vovk 2010; F. Tavecchio et al. 2010; R. Durrer & A. Neronov 2013; K. Takahashi et al. 2013; P. A. R. Ade et al. 2016; M. S. Pshirkov et al. 2016; K. Jedamzik & A. Saveliev 2019; V. Domcke & C. Garcia-Cely 2021). Second, it is evident that the signal’s effective field of vision cannot surpass the telescope’s field of view (see our discussion of this in Appendix B). Therefore, we can consider the following simple model: The telescope is centered on a neutron star, and the data at the back end of the observation are actually the integrated total voltage of all radio signals across the telescope’s field of view (A. R. Thompson et al. 2017). It is clear that Rtot is greater than roccur for actual observation. Therefore, we can determine the total energy flux reaching Earth

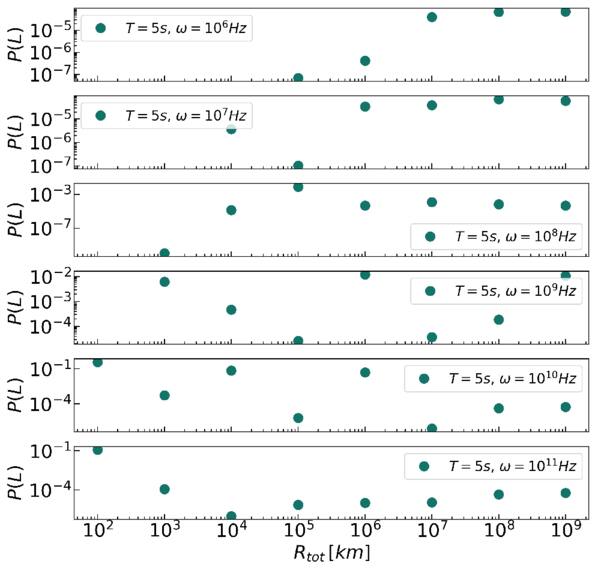

Combining these points, we calculated the integral conversion probability  with the change of size of the conversion region Rtot. The results are presented in Figure 4, utilizing the same parameters as in Figure 2. The complete results are available in Figure 19 in Appendix D. The absence of data points in the figure at lower frequencies is attributed to the radius at which conversion occurs, roccur, being greater than the radius of the conversion region, Rtot, assumed in our calculation. The figure demonstrates that the decrease in the total conversion probability near the neutron star’s light cylinder, RCL ≃ 2.5 × 105 km, is due to changes in the topological configuration of the magnetic field in that region. Simultaneously, it is observed that, when the radius of this region exceeds 1 × 108 km, the total conversion probability curve approaches a flat trend. This phenomenon occurs because the magnetic field of the neutron star decays with the third power of the radius, leading to the superposition of the conversion probability from the larger region being considered a higher-order term. Finally, we selected the radius of the conversion region as Rtot = 109 km. The radius is less than the field-of-view radius of the telescope, and the magnetic field strength exceeds 47 pGauss. The selected conversion region represents an optimistic estimate, and actual observations are likely to differ significantly: (a) Due to the magnetic field crossing of the surrounding objects, the magnetic field of the neutron star does not have such a clear dividing line. (b) We assumed that the physical process of converting VHF GWs into electromagnetic waves occurs uniformly throughout the conversion region. However, VHF GWs may be localized to a limited area within this conversion region, necessitating observations to accurately identify the emission region of electromagnetic waves.

with the change of size of the conversion region Rtot. The results are presented in Figure 4, utilizing the same parameters as in Figure 2. The complete results are available in Figure 19 in Appendix D. The absence of data points in the figure at lower frequencies is attributed to the radius at which conversion occurs, roccur, being greater than the radius of the conversion region, Rtot, assumed in our calculation. The figure demonstrates that the decrease in the total conversion probability near the neutron star’s light cylinder, RCL ≃ 2.5 × 105 km, is due to changes in the topological configuration of the magnetic field in that region. Simultaneously, it is observed that, when the radius of this region exceeds 1 × 108 km, the total conversion probability curve approaches a flat trend. This phenomenon occurs because the magnetic field of the neutron star decays with the third power of the radius, leading to the superposition of the conversion probability from the larger region being considered a higher-order term. Finally, we selected the radius of the conversion region as Rtot = 109 km. The radius is less than the field-of-view radius of the telescope, and the magnetic field strength exceeds 47 pGauss. The selected conversion region represents an optimistic estimate, and actual observations are likely to differ significantly: (a) Due to the magnetic field crossing of the surrounding objects, the magnetic field of the neutron star does not have such a clear dividing line. (b) We assumed that the physical process of converting VHF GWs into electromagnetic waves occurs uniformly throughout the conversion region. However, VHF GWs may be localized to a limited area within this conversion region, necessitating observations to accurately identify the emission region of electromagnetic waves.

Figure 4. The total conversion probability  of the GWs traveling at different Rtot in neutron star magnetic field. The parameters of the magnetic field assumed are B = 1014 Gauss, and

of the GWs traveling at different Rtot in neutron star magnetic field. The parameters of the magnetic field assumed are B = 1014 Gauss, and  . The figure shows from top to bottom the result of a tenfold increase in the frequency of the radio telescope at one time, and the conversion probability as a whole gradually increases.

. The figure shows from top to bottom the result of a tenfold increase in the frequency of the radio telescope at one time, and the conversion probability as a whole gradually increases.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution image2.2. Diffraction of Gravitational Waves by Single Neutron Star

Recent studies have revealed that, when nanohertz GWs pass through the Universe, they will produce weak interference modulation due to the diffraction effect of a large number of galactic disks, and the strain amplitude will change about  (D. L. Jow & U.-L. Pen 2025). Similarly, when a VHF GW passes through a neutron star’s magnetic field, the GW is also diffracted by the neutron star, which we discuss in this subsection and give the amount of change in the modulated strain amplitude.

(D. L. Jow & U.-L. Pen 2025). Similarly, when a VHF GW passes through a neutron star’s magnetic field, the GW is also diffracted by the neutron star, which we discuss in this subsection and give the amount of change in the modulated strain amplitude.

A solar mass neutron star with a radius of 10 km has a Schwarzschild radius  of about 3 km < r0, and the Fresnel length can be calculated to determine whether GWs will be diffracted as they pass by the neutron star. The Fresnel length, which relates to the GW frequency and the distance between the neutron star and radio telescope, can be described as (R. Takahashi & T. Nakamura 2003; J.-P. Macquart 2004; K. S. Thorne & R. D. Blandford 2017; H. G. Choi et al. 2021)

of about 3 km < r0, and the Fresnel length can be calculated to determine whether GWs will be diffracted as they pass by the neutron star. The Fresnel length, which relates to the GW frequency and the distance between the neutron star and radio telescope, can be described as (R. Takahashi & T. Nakamura 2003; J.-P. Macquart 2004; K. S. Thorne & R. D. Blandford 2017; H. G. Choi et al. 2021)

Here, deff = dLdLS/dS ≈ dL denotes the effective angular diameter distance to the lens, where dL is the distance from the neutron star to the Earth. This approximation holds under the assumption that the incident GWs can be treated as plane waves, implying that their sources either lie beyond the Milky Way or originate from the very early Universe. Then, the condition for diffraction is  (R. Takahashi 2006; M. Oguri & R. Takahashi 2020; H. G. Choi et al. 2021). It is clear that GWs in the radio band 106–1010 Hz combined with distant neutron stars satisfy the diffraction condition. The frequency dependence in the diffraction regime is measured by the shear γ(x) from the complex amplification factor with Kirchhoff–Fresnel integral Famp(ω) =

(R. Takahashi 2006; M. Oguri & R. Takahashi 2020; H. G. Choi et al. 2021). It is clear that GWs in the radio band 106–1010 Hz combined with distant neutron stars satisfy the diffraction condition. The frequency dependence in the diffraction regime is measured by the shear γ(x) from the complex amplification factor with Kirchhoff–Fresnel integral Famp(ω) = ![$\frac{\omega }{i{d}_{{\rm{eff}}}}\int {d}^{2}{\boldsymbol{r}}\exp \left[i2\pi \omega {T}_{d}\left({\boldsymbol{r}},{{\boldsymbol{r}}}_{s}\right)\right]$](https://content.cld.iop.org/journals/0004-637X/990/2/156/revision1/apjadf19aieqn76.gif) (T. T. Nakamura & S. Deguchi 1999). Here, r denotes the physical displacement vector on the lens plane, measured from the center of the lens, and rs represents the projected position of the source onto the same plane. The quantity Td is the arrival-time difference between the deflected trajectory passing through r under the influence of the lens and the unperturbed, straight-line path that would occur in the absence of the lens. In an analogy with the energy density spectrum of GWs, reformulating the Kirchhoff–Fresnel integral in terms of a logarithmic frequency interval proves advantageous for the analysis that follows (H. G. Choi et al. 2021)

(T. T. Nakamura & S. Deguchi 1999). Here, r denotes the physical displacement vector on the lens plane, measured from the center of the lens, and rs represents the projected position of the source onto the same plane. The quantity Td is the arrival-time difference between the deflected trajectory passing through r under the influence of the lens and the unperturbed, straight-line path that would occur in the absence of the lens. In an analogy with the energy density spectrum of GWs, reformulating the Kirchhoff–Fresnel integral in terms of a logarithmic frequency interval proves advantageous for the analysis that follows (H. G. Choi et al. 2021)

To obtain a fast estimate of the cumulative diffraction amplification factor, we consider only the single diffraction flux formed by the contribution of the isolated neutron star. The diffraction amplification factor, which is the energy amplification by the GW due to the diffraction of the neutron star, is the bridge between before and after GWs are diffracted

where hdiff(ω) denotes the lensed waveform, while h(ω) represents the unlensed waveform. And both are expressed in the frequency domain with respect to the frequency ω. Therefore, the GW sensitivity we observe needs to be divided by the diffraction amplification factor Famp(ω) (D. L. Jow & U.-L. Pen 2025). Given that the spatial scale of the neutron star magnetosphere under consideration greatly exceeds the Fresnel scale, the characteristic transverse size of the lensing structure is much larger than the Fresnel radius. Under such conditions, the lens can be effectively treated as one-dimensional, and the resulting diffracted flux is well approximated by the diffraction pattern of a one-dimensional Gaussian lens

For example, if the distance parameter dL = 2 kpc of PSR J0501+4516 is selected and the frequency ω is 106 Hz, Famp is equal to 0.176. It should be noted that GWs in the radio band are still tensor waves, and the diffraction formula we use is a reasonable approximation (S. R. Dolan 2017; S. Hou et al. 2019; J.-h. He 2020; D. L. Jow et al. 2020; Z. Li et al. 2022). In principle, a more precise tensor diffraction formula is needed to describe the properties of tensor waves, which we will discuss in a subsequent paper.

3. Signal Spectral Line Characteristics and Frequency Characteristics

VHF GWs are transformed into electromagnetic waves through the GZ effect in the magnetic fields of neutron stars. The signal spectral lines and frequency characteristics of these waves are the keys to detection and physical analysis. This section systematically expounds the spectral line characteristics of graviton–photon conversion and the frequency dependence of signal propagation.

3.1. The Graviton Spectral Line Broadening

In this subsection, we will discuss the line-broadening mechanism of gravitons. The order of discussion is collision broadening, the Zeeman effect in a magnetic field, and natural broadening.

The Lorentz transformation allows us to represent the GW amplitudes h+ and h× under the GW’s transverse and traceless gauge

If we assume rotations around the axis, the combinations h× ± ih+ undergo a transformation

Another characteristic of GWs is that they adhere to the massless Klein–Gordon field equation

Therefore, we can examine the massless, one-dimensional representation of the Poincaré group, which is defined by the condition of four-momentum PμPμ = 0 and is characterized by a specific value of the helicity h. The helicity h is defined as the projection of total angular momentum onto the direction of motion, expressed as  , where

, where  represents the propagation direction of the GW, and J = L + S denotes the total angular momentum, which is the sum of the orbital angular momentum L and spin angular momentum S. Upon rotating the direction of motion by an angle ψ, the helicity eigenstate ∣h〉 is transformed as follows:

represents the propagation direction of the GW, and J = L + S denotes the total angular momentum, which is the sum of the orbital angular momentum L and spin angular momentum S. Upon rotating the direction of motion by an angle ψ, the helicity eigenstate ∣h〉 is transformed as follows:

By combining Equations (17) and (19), the helicity of GWs, as well as that of massless gravitons, can be determined to be h = ±2. In conclusion, gravitons, massless particles with a helicity ±2 that propagate along null geodesics, are compatible with the linearization of general relativity and contemporary quantum field theory. This indicates that their theoretical speed ought to equal the speed of light, denoted as c. Observations have verified this, indicating that the speed of gravitational waves is nearly equivalent to the speed of light (A. E. Romano & M. Sakellariadou 2025).

Because the massless gravitons propagate along null geodesics, there is no change in their velocity, and therefore no Maxwell velocity distribution law for them. Hence, the frequency distribution fd(ω) at the temperature T broadened by the collision of spectral lines is invalid

where  , where ω0 represents the fundamental frequency, and the most probable speed is given by

, where ω0 represents the fundamental frequency, and the most probable speed is given by  . Simultaneously, we observe that several studies suggest that gravitons can have mass (D. M. Eardley et al. 1973; B. P. Abbott et al. 2016b, 2017a, 2017b, 2019b; M. Isi et al. 2019; E. Payne et al. 2023; T. Flöss et al. 2024; Y. Hatta 2024). The distribution of collisional broadening can be derived in the presence of mass using Equation (20). Then, the full width at half-maximum (FWHM) points of massive gravitons can be determined.

. Simultaneously, we observe that several studies suggest that gravitons can have mass (D. M. Eardley et al. 1973; B. P. Abbott et al. 2016b, 2017a, 2017b, 2019b; M. Isi et al. 2019; E. Payne et al. 2023; T. Flöss et al. 2024; Y. Hatta 2024). The distribution of collisional broadening can be derived in the presence of mass using Equation (20). Then, the full width at half-maximum (FWHM) points of massive gravitons can be determined.

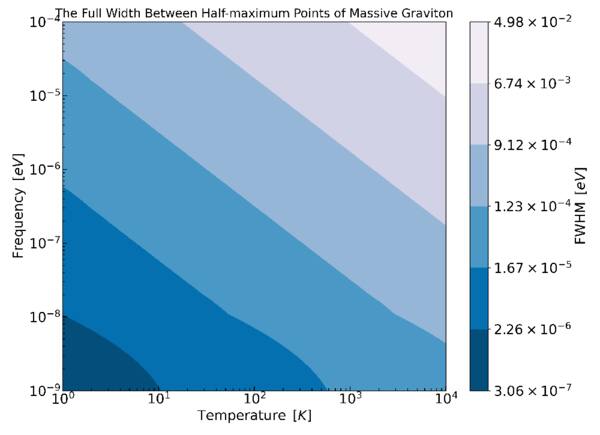

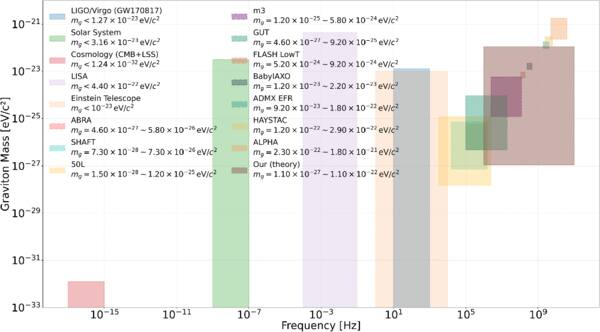

where kB signifies the Boltzmann constant, and Te indicates the temperature of the neutron star magnetosphere. Figure 5 presents the FWHM for massive gravitons. The mass of gravitons is determined to be mg = 10−9–10−4 eV, corresponding to frequencies of ω ≈ 106–1011 Hz. Furthermore, in Figure 6, we present the constraints imposed by current graviton observations and experiments on its mass range. The quality range limit of the method discussed in this paper is denoted by a brown slash. The quality limit range of our method is somewhat narrower than that of other experiments, featuring a marginally higher upper limit. The final observational results reveal distinct characteristics that enable the determination of various graviton masses and the analysis of gravitational theories.

Figure 5. The FWHM of massive gravitons at different observational frequencies and temperatures is derived from collisions of spectral lines fd(ω). In the panel, the FWHM is represented by different colored filled contours. Moreover, fd(ω) satisfies the normalization condition ∫fd(ω)dω = 1.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageFigure 6. Current and prospective experimental constraints on graviton mass. The various colored regions in the panel indicate the frequency ranges identified by different experiments in relation to graviton constraints. Various experiments indicate the mass of the graviton, as reported in studies (C. Cutler et al. 2003; K. G. Arun & C. M. Will 2009; D. Bessada & O. D. Miranda 2009; M. Punturo et al. 2010; M. Goryachev & M. E. Tobar 2014; B. M. Brubaker 2017; N. Du et al. 2018; M. Lawson et al. 2019; L. Bernus et al. 2020; T. Braine et al. 2020; M. Maggiore et al. 2020; M. Salatino et al. 2020; R. Abbott et al. 2021b; A. Abeln et al. 2021; C. Bartram et al. 2021; A. V. Gramolin et al. 2021; C. P. Salemi et al. 2021; V. Domcke et al. 2022; S. Ahyoune et al. 2023; D. Alesini et al. 2023; A. J. Millar et al. 2023; C. Gatti et al. 2024). Brown diagonal lines occupy the region indicative of our potentially observable mass range.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageFurthermore, the helicity of massless gravitons causes the Zeeman effect to inhibit the spectral lines from splitting into multiple transitions among their magnetic sublevels, as transitions with Δm = 0 and Δm = ±1 are permitted according to selection rules. The shifted transitional frequency ΔωZ between magnetic sublevels equals zero

where J1 represents the angular momentum of the upper state, and J2 denotes the angular momentum of the lower state. m1 and m2 represent the magnetic quantum numbers. Besides, μB denotes the Bohr magneton; ℏ represents the reduced Planck’s constant; g1 and g2 signify the g-factors of the two states; and B indicates the magnetic field. Next, we can calculate the natural line width using the uncertainty principle

where ΔE is represented as hΔωnat, while Δt relates to the spontaneous emission rate of gravitons as per Bohr’s correspondence principle. Given the current lack of knowledge regarding the internal structure of gravitons, and considering that gravitons exhibit a helicity of ±2, it can be inferred that Δt approaches infinity. Consequently, the natural frequency, Δωnat, tends toward zero, rendering the natural broadening negligible.

In conclusion, we believe that, in traditional general relativity, the broadening of massive gravitons is negligible, and massless gravitons exhibit no spectral line broadening. Consequently, the spectral line broadening of the photon signal transformed by the inverse GZ effect is minimal and can be effectively considered negligible. We can differentiate the radio signal from other typical astrophysical processes once we ascertain its shape and specific spectral line attributes. In the subsequent subsection, we will examine the frequency-dependent characteristics of this signal.

3.2. Signal Frequency Characteristics

In contrast to gravitons, which exhibit minimal interaction with matter due to their exceedingly small cross section, photons traversing the Universe undergo scattering by matter or celestial entities, including electrons and protons. Therefore, it is essential to consider the energy depletion of photons in radio observations. To maintain generality, we concentrate exclusively on the scattering of photons converted by GWs through electrons during their propagation, as the energy variation of an electromagnetic wave is directly associated with its trajectory. In a medium of small optical thickness, the probability of photon scattering through the medium is given by  . According to the law of large numbers, when a photon traverses the same medium M times (M → ∞), the total number of scattering events is Mτes. Consequently, the number of scattering events occurring through the medium only once is

. According to the law of large numbers, when a photon traverses the same medium M times (M → ∞), the total number of scattering events is Mτes. Consequently, the number of scattering events occurring through the medium only once is  . In an optically thick medium, the number of times photons are scattered, denoted as N, can be calculated using random walk theory as

. In an optically thick medium, the number of times photons are scattered, denoted as N, can be calculated using random walk theory as  , where τes = neσTR. Moreover, ne represents the electron density. The Thomson scattering cross section is given by

, where τes = neσTR. Moreover, ne represents the electron density. The Thomson scattering cross section is given by  , where

, where  is the classical electron radius, and R signifies the medium scale. Consequently, for a medium with any optical thickness, the typical scattering number can be represented as

is the classical electron radius, and R signifies the medium scale. Consequently, for a medium with any optical thickness, the typical scattering number can be represented as  . The Compton y-parameter serves as a metric for assessing the significance of scattering. The total energy change is determined by multiplying the average energy change per scattering event by the total number of scatterings.

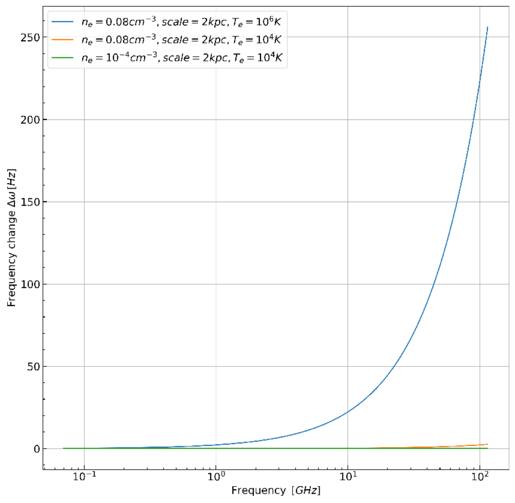

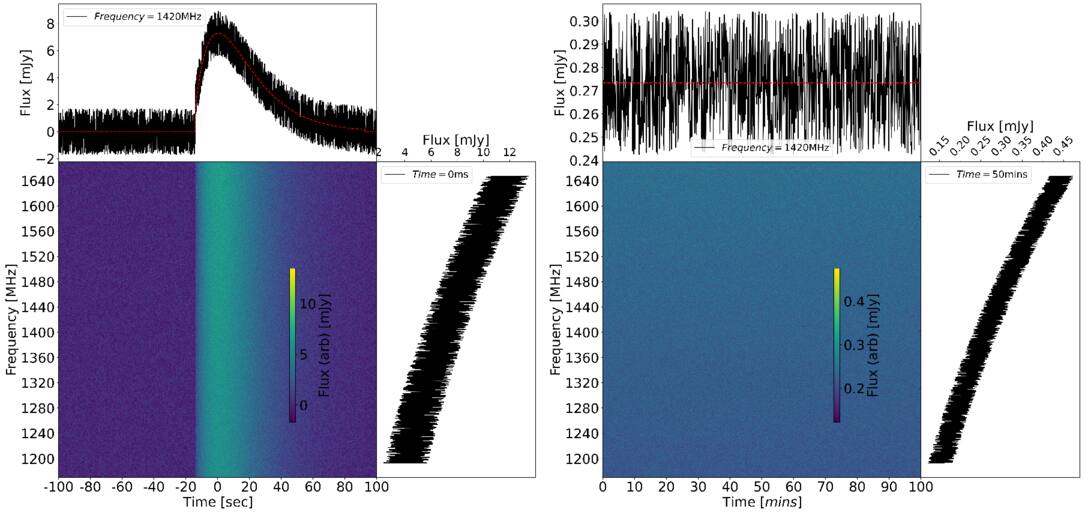

. The Compton y-parameter serves as a metric for assessing the significance of scattering. The total energy change is determined by multiplying the average energy change per scattering event by the total number of scatterings. ![${y}_{\mathrm{com},\mathrm{eff}}=N\left[{\left(\tfrac{4{k}_{{\rm{B}}}{T}_{e}}{{m}_{e}{c}^{2}}\right)}^{2}+\tfrac{4{k}_{{\rm{B}}}{T}_{e}}{{m}_{e}{c}^{2}}-\tfrac{\hslash \omega }{{m}_{e}{c}^{2}}\right]$](https://content.cld.iop.org/journals/0004-637X/990/2/156/revision1/apjadf19aieqn87.gif) . Subsequent articles will analyze the interstellar scintillation of a pulsar to develop a more accurate model of energy loss in signal propagation. We choose representative electron densities ne = 0.08 cm−3 and ne = 10−4 cm−3 with electron temperatures for a diffuse ionized component of Te = 104 K and Te = 106 K. These data are utilized to plot Figure 7, illustrating the total frequency variation of converted photons from the magnetar to the telescope as a result of Compton scattering. This suggests that targeting neutron stars with elevated electron temperatures and densities along the path to Earth can enhance the distinguishability of the GW signal.

. Subsequent articles will analyze the interstellar scintillation of a pulsar to develop a more accurate model of energy loss in signal propagation. We choose representative electron densities ne = 0.08 cm−3 and ne = 10−4 cm−3 with electron temperatures for a diffuse ionized component of Te = 104 K and Te = 106 K. These data are utilized to plot Figure 7, illustrating the total frequency variation of converted photons from the magnetar to the telescope as a result of Compton scattering. This suggests that targeting neutron stars with elevated electron temperatures and densities along the path to Earth can enhance the distinguishability of the GW signal.

Figure 7. Compton scattering of electrons results in a change in the frequency of photons. The blue line represents an electron number density of ne = 0.08 cm−3, a medium scale of R = 2 kpc, and an electron temperature of Te = 106 K. The yellow line represents an electron number density of ne = 0.08 cm−3, a medium scale of R = 2 kpc, and an electron temperature of Te = 104 K. The green line represents an electron number density of ne = 10−4 cm−3, medium scale R = 2 kpc, electron temperature Te = 104 K.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageRadio data processing typically entails the extraction of signals from radio observation data and the differentiation of various target sources through the utilization of polarization information from radiation sources. Four Stokes parameters can characterize the polarization features of a quasi-monochromatic electromagnetic wave

where  and

and  , assuming the scalar potentials are set to zero. The parameter I denotes total intensity, while Q and U represent linear polarization and its position angle, respectively. The symbol V signifies circular polarization. Utilizing the four Stokes parameters, the observed polarization angle is defined as

, assuming the scalar potentials are set to zero. The parameter I denotes total intensity, while Q and U represent linear polarization and its position angle, respectively. The symbol V signifies circular polarization. Utilizing the four Stokes parameters, the observed polarization angle is defined as  , the linear polarization is given by

, the linear polarization is given by  , the circular polarization is expressed as

, the circular polarization is expressed as  , and the overall degree of polarization is represented by

, and the overall degree of polarization is represented by  . Additionally, a four-vector can be defined using the Stokes parameters, which can be transformed by the generalized Faraday rotation tensor ραβ (D. B. Melrose & R. C. McPhedran 1991; V. N. Sazonov 1969), incorporating Faraday rotation and conversion coefficients and the absorption tensor ηαβ in relation to the absorption coefficients of Stokes parameters (D. B. Melrose & R. C. McPhedran 1991; V. N. Sazonov 1969). This results in the general radiation transfer equation

. Additionally, a four-vector can be defined using the Stokes parameters, which can be transformed by the generalized Faraday rotation tensor ραβ (D. B. Melrose & R. C. McPhedran 1991; V. N. Sazonov 1969), incorporating Faraday rotation and conversion coefficients and the absorption tensor ηαβ in relation to the absorption coefficients of Stokes parameters (D. B. Melrose & R. C. McPhedran 1991; V. N. Sazonov 1969). This results in the general radiation transfer equation

where  represent the vector of four Stokes parameters. The indices i = j = 1, 2, 3, 4 correspond to the components labeled as I, Q, U, V, while

represent the vector of four Stokes parameters. The indices i = j = 1, 2, 3, 4 correspond to the components labeled as I, Q, U, V, while i denotes the coefficients of spontaneous emission.

However, the polarization angle Φ is subject to the influence of Faraday rotation, which is characterized by the rotation measure (RM). Faraday rotation is an optical effect where the polarization plane undergoes a linear rotation with the square of the wavelength  , expressed as

, expressed as  . The RM is directly linked to the magnetic field aligned with the line of sight (LOS), considering the free electron density integrated along the path from the source to the observer. There are several methods for measuring the Faraday rotation, or RM of polarized astrophysical signals, such as RM synthesis, wavelet analysis, compressive sampling, and QU-fitting (X. H. Sun et al. 2015). In this paper, we employ RM synthesis along with Faraday synthesis. RM synthesis (B. J. Burn 1966; M. A. Brentjens & A. G. de Bruyn 2005) is a robust technique for quantifying Faraday rotation, akin to a Fourier transformation

. The RM is directly linked to the magnetic field aligned with the line of sight (LOS), considering the free electron density integrated along the path from the source to the observer. There are several methods for measuring the Faraday rotation, or RM of polarized astrophysical signals, such as RM synthesis, wavelet analysis, compressive sampling, and QU-fitting (X. H. Sun et al. 2015). In this paper, we employ RM synthesis along with Faraday synthesis. RM synthesis (B. J. Burn 1966; M. A. Brentjens & A. G. de Bruyn 2005) is a robust technique for quantifying Faraday rotation, akin to a Fourier transformation

where ϕ represents the Faraday depth; an extension of RM is used when the polarized signal is subject to varying degrees of Faraday rotation. Repeating this process for various ϕ values produces a Faraday dispersion function that shows the polarized intensity at different test levels. When RM synthesis is applied to emission spread over a large area of space, it often results in a complicated Faraday dispersion function with significant polarized emission at various Faraday depths (C. S. Anderson et al. 2016; J. M. Dickey et al. 2019). At times, the polarization effect from the detected source varies over time, requiring the use of the polarization position angle to analyze the results. The polarization position angle differs from the observed polarization angle Φ since it describes the orientation of the polarized signal before being affected by Faraday rotation. We can use the observed RM as a multiplicative phase factor to counteract the rotation of the spectrum and eliminate the impact of Faraday rotation

where [Q + iU]obs is the observed spectrum, and [Q + iU]source is the intrinsic polarization vector at the source, while RM and Φ0 are fitted parameters. Φ0 is the polarization position angle at a reference wavelength  . In the case of calibrated polarized observations, Φ0 is often referenced at infinite frequency where Faraday rotation is zero. In principle, any time dependence of Φ0 can be determined by fitting the polarized signal through the burst duration. This time-resolved analysis is hard to do in practice because of S/N limitations. It is also not good for an automated pipeline that needs reliable ways to describe the polarized signal. An alternative method for characterizing time dependence in Φ0 is to apply the observed polarization angle