Abstract

We present a new empirical Type Ia supernova (SN Ia) model with three chromatic flux variation templates: one phase dependent and two phase independent. No underlying dust extinction model or patterns of intrinsic variability are assumed. Implemented with Stan and trained using spectrally binned Nearby Supernova Factory spectrophotometry, we examine this model's 2D, phase-independent flux variation space using two motivated basis representations. In both, the first phase-independent template captures variation that appears dust-like, while the second captures a combination of effectively intrinsic variability and second-order dust-like effects. We find that ≈13% of the modeled phase-independent flux variance is not dust-like. Previous empirical SN Ia models either assume an effective dust extinction recipe in their architecture, or only allow for a single mode of phase-independent variation. The presented results demonstrate such an approach may be insufficient, because it could “leak” noticeable intrinsic variation into phase-independent templates.

Original content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 licence. Any further distribution of this work must maintain attribution to the author(s) and the title of the work, journal citation and DOI.

1. Introduction

The discovery of dark energy with standardized Type Ia supernovae (SNe Ia) solidified these transient objects' importance to cosmology (A. G. Riess et al. 1998b; S. Perlmutter et al. 1999). SNe Ia exhibit a markedly similar peak B-band brightness dispersion of only ~1 mag, and this dispersion can be reduced further with multifilter photometric time series (or light curves) by exploiting correlations between light-curve duration (also called shape, width, or stretch) and color with B-band maximum brightness (M. M. Phillips 1993; A. G. Riess et al. 1996; S. Perlmutter et al. 1997; R. Tripp 1998). These standardization results reduce the brightness dispersion by an order of magnitude to ≈0.12 mag (D. M. Scolnic et al. 2018). Standardization using spectra can reduce the dispersion even further, to ≈0.08 mag (H. K. Fakhouri et al. 2015; K. Boone et al. 2021a).

There are two errors that limit the capacity of SNe Ia to constrain cosmological parameters: the number of observed SNe Ia (statistical uncertainty), and errors resulting from observation bias, modeling errors, and calibration (systematics). Recent SN Ia cosmology analyses have significantly reduced the statistical uncertainty by utilizing over 103 spectroscopically confirmed SNe Ia (M. Betoule et al. 2014; D. M. Scolnic et al. 2018). LSST, via the Vera Rubin Observatory, will further increase our usable SN Ia sample by at least an order of magnitude over 10 yr after its commissioning (Ž. Ivezić et al 2019). Although internal photometric calibration will remain an important systematic to account for, LSST will alleviate tedious intersurvey photometric calibration systematics performed in many past analyses while still providing impressive statistics. As a result, LSST will increase the relative importance of systematics arising from SN Ia light-curve modeling and standardization for constraining cosmological parameters.

SNe Ia result from the catastrophic disruption of carbon–oxygen white dwarfs (F. Hoyle & W. A. Fowler 1960). Potential progenitor scenarios include accretion from a white dwarf's companion star or merging/collision of white dwarf binary constituents (J. Whelan & I. J. Iben 1973; I. J. Iben & A. V. Tutukov 1984). Unfortunately, accounting for observed SN Ia spectral variation while simultaneously recovering established empirical relations within the context of a detonating (or deflagrating) white dwarf framework remains a daunting and incomplete task. For example, it is suggested that progenitor mass can extend below an otherwise expected white dwarf mass limit, or Chandrasekhar mass, of 1.4 M⊙ (R. A. Scalzo et al. 2014). See N. Soker (2019) for a recent review of and summary of SN Ia theoretical modeling progress and unanswered questions. Usable parametric theoretical SN Ia models remain elusive, leaving us reliant on empirical models trained from SN Ia observations.

1.1. Photometric Variation and Empirical Models

As mentioned, light-curve width correlates with B-band maximum brightness so that longer duration SNe Ia are systematically brighter (M. M. Phillips 1993). We refer to this as the width–luminosity relation (WLR). Similarly, bluer SN Ia light curves are systematically brighter at B-band maximum, which we similarly refer to as the color–luminosity relation (A. G. Riess et al. 1996).

One can interpret SN Ia empirical models as transforming high-dimensional sets of observations to a lower-dimensional set of parametric latent templates that inscribe dominant modes of SN Ia variability. The first generation of models attempted to describe light curves in standard rest-frame filters using templates specific to those filters (A. G. Riess et al. 1996; S. Jha et al. 2007; C. R. Burns et al. 2011), which when applied to measurements made with different rest-frame filters required a K-correction (A. Kim et al. 1996; P. Nugent et al. 2002) to convert the data to the model photometric system. The limitations of models based on broadband templates were quickly recognized: K-corrections carry their own set of uncertainties and biases that are correlated with model parameters (K. S. Mandel et al. 2022). More importantly, by restricting the templates to broad band, these models were insensitive to substantially more complex SN Ia variability revealed through spectroscopy.

SN Ia spectral variability is either intrinsic to SN Ia populations or is extrinsic, instead arising from processes external to the explosion, such as dust extinction or the SN Ia's interaction with its circumstellar environments (P. Nugent et al. 2002; S. Jha et al. 2007). Furthermore, photometric relationships emerge from spectral variation, with the temperature dependence of Fe line blanketing at least partly driving the WLR and explaining its wavelength dependence being such an example (D. Kasen & S. E. Woosley 2007). Variation in progenitor mass also contributes to the WLR, as lower-mass SN Ia progenitors are systematically dimmer and have faster-declining light curves compared to their more massive counterparts (R. A. Scalzo et al. 2014). Certain spectral features directly correlate with photometric SN Ia properties, such as the F(6420 Å)/F(4430 Å) line ratio correlating with maximum B-band brightness (S. Bailey et al. 2009), and the ratio of Si ii 5972 and 6355 Å (or Si ii 5972 and 3858 Å) correlating with light-curve width (P. Nugent et al. 1995).

Many SN Ia subtypes have been categorized by their spectral variation (D. Branch et al. 2009; S. Blondin et al. 2012). Grouping SNe Ia based on Si ii velocity at maximum brightness during a Tripp standardization procedure (R. Tripp 1998) has been shown to reduce SN Ia dispersion poststandardization more than use of only color and stretch alone (X. Wang et al. 2009; R. J. Foley 2013). Furthermore, spectral information can improve the effective total-to-selective extinction RV estimation, with N. Chotard et al. (2011) using spectral features to recover an effective RV value consistent the Milky Way average of RV = 3.1. Given this plethora of spectral variety within SNe Ia, and this variety's potential to further improve standardization, commonly used and recent SN Ia models make heavy use of spectroscopic observations in training.

Most recent SN Ia models reduce the dimensionality of SN Ia observations by constructing combinations of underlying spectral or color variation templates, with one template capturing the average, or fiducial, spectral evolution of SNe Ia. This approach removes any need for K-corrections and related uncertainty propagation (J. Guy et al. 2007; K. S. Mandel et al. 2022). The ubiquitous SALT model family (and its cousin SiFTO) is the canonical example of the spectral template technique (J. Guy et al. 2007; A. Conley et al. 2008; M. Betoule et al. 2014; J. D. R. Pierel et al. 2022). This family of linear SN Ia models captures variation beyond a mean spectral surface with a first-order flux variation template and a phase-independent color template (with per-SN contribution parameters x1 and c, respectively). SALT2's success over prior models saw its widespread adoption and continuous improvement, with the most recent version SALT3 extending its wavelength coverage to the near-infrared (NIR; W. D. Kenworthy et al. 2021). More statistically rigorous linear spectral template models have also been developed, such as BayeSN with its potent hierarchical Bayesian framework (K. S. Mandel et al. 2017, 2022; S. Thorp et al. 2021).

A plethora of sophisticated models have recently been developed using The Nearby Supernova Factory (SNfactory) spectrophotometric time series (G. Aldering et al. 2002). C. Saunders et al. (2018) and their SNEMO model extracts up to 15 linear principal functional components from a set of SN Ia spectral surfaces trained using Gaussian processes to maximally explain SN Ia variation. Alternatively, P. F. Léget et al. (2020) in their SUGAR model treats SN Ia variation as a linear combination of spectral index templates, extending the initial work of N. Chotard et al. (2011) into a fully generative model. SNEMO and SUGAR, along with all the models mentioned so far, utilize linear dimensionality reduction techniques.

K. Boone et al. (2021b) apply the Isomap method with their Twins Embedding model to train a nonlinear parameterization of intrinsic SN Ia variation at maximum brightness, while G. Stein et al. (2022) introduce a nonlinear probabilistic autoencoder that captures intrinsic variation across both wavelength and phase. Both find that a nonlinear approach requires only three intrinsic model components to describe SN Ia spectral variation where more traditional linear principal component analysis model would require seven components or more (C. Saunders et al. 2018). These two models also demonstrate noticeable improvements over SALT2 in standardized SN Ia dispersion from ≈0.12 to ≲0.09 mag. Improvements through nonlinear technique application are not limited to light-curve models: D. Rubin et al. (2015) introduce the hierarchical Bayesian framework UNITY that allows for nonlinear standardization, leading again to improved SN Ia dispersion poststandardization relative to the linear Tripp approach.

1.2. Shortcomings in Phase-independent Modeling

All past models either assume a dust extinction model for explicit phase-independent templates (MCLS2k2, SNooPY, SNEMO, SUGAR, BayeSN, and current nonlinear models) or include a single phase-independent template which does not differentiate between intrinsic and extrinsic variation (the SALT family). Excluding the maximum brightness model Twins Embedding, each of these models characterize phase-independent variability with only a single model component. Physical considerations alone demonstrate this to be an insufficient treatment. As summarized in J. C. Weingartner & B. T. Draine (2001), one would expect at least two extrinsic variation parameters per SN Ia: one gauging dust column density or optical depth (i.e., AV) and the other probing second-order characteristics such as dust grain properties (i.e., RV). Furthermore, it is plausible that empirical SN Ia models could extract intrinsic variation into a phase-independent template set. In this era of precision cosmology, modeling and standardization systematics remain stubborn obstacles to maximizing current and future SN Ia survey utility. Better understanding underlying extracted modes of phase-independent variation could answer outstanding questions about the SN Ia population (i.e., the low SN Ia RV debate or the source of the bias associated with host properties), and improve both SN Ia modeling and standardization.

We present a new SN Ia empirical model to more deeply explore the phase-independent variability of SNe Ia. This model features three chromatic flux variation templates: one phase dependent and two phase independent. These two phase-dependent components provide the flexibility to account for multiparameter dust models while also absorbing an intrinsic time-averaged flux variation beyond that accounted for by the phase-dependent component. All templates are physics agnostic, as no assumptions are made about expected spectral features or dust treatment. This new model is trained on SNfactory's rest-frame spectrophotometric time series.

Our model bears some similarities with BayeSN. Both models are linear models implemented with Stan. How phase-independent variability is accounted for varies in approach, though. BayeSN implements a single-component dust extinction recipe within a hierarchical model framework, from which they recover an effective RV that is largely consistent with the Milky Way average. In contrast, our model has two phase-independent templates, providing it two model degrees of freedom for which no physical assumptions are made. Unlike BayeSN, our model does not model spectral surface residuals.

In Section 2 we introduce the training set and its quality cuts. We describe our model and fitting technique in Section 3, with global model template and refit per-SN parameter results being presented in Section 4. Finally, we provide concluding remarks in Section 5.

2. Data

Between 2004 and 2014 SNfactory observed spectrophotometric time series of nearly 300 SNe Ia (G. Aldering et al. 2002) with the SuperNova Integral Field Spectrograph (SNIFS; B. Lantz et al. 2004). SNIFS is continuously mounted at the University of Hawai'i 2.2 m telescope, using dual-channel, moderate resolution (R ~ 600–1300) spectrographs to simultaneously observe transient events from 3200 to 5200 Å and 5100–10000 Å, respectively. This unique and homogeneous SN Ia data set is calibrated with CALSPEC and Hamuy standard stars (M. Hamuy et al. 1992, 1994; R. C. Bohlin 2014). The photometric calibration method is largely summarized in C. Buton et al. (2013) with R. Pereira et al. (2013) further describing non-photometric-night calibration. Host-galaxy-subtraction methodology is presented in S. Bongard et al. (2011). Each SNe Ia has also been fit using SALT2.4 (M. Betoule et al. 2014).

For our SN Ia training sample we generate synthetic SN-frame photometry using nλ log-distributed top-hat filters from published rest-frame SNfactory spectra (G. Aldering et al. 2020). These spectra were first corrected for Milky Way extinction, then their wavelengths were de-redshifted (from an initial range of approximately 0.01 < z < 0.08), and then they are placed on a relative luminosity scale (i.e., that equivalent to having been observed at z = 0.05). Cosmological time dilation is accounted for during de-redshifting. Observed spectra are in units of 1010 erg s−1 cm−2. This work does not attempt to fit absolute magnitudes or fit for cosmological parameters, so per-SN redshifts are not used. Due to high-flux variance at wavelength boundaries, and because most objects have a higher redshift than z = 0.05, the per-spectra reference frame wavelength range is truncated to between 3350 and 8030 Å.

The spectral resolution of this top-hat filter synthetic photometry is flexible—for this work, we use a modest nλ = 10 filter count. These nλ = 10 bins are spaced at constant spectral resolution R, providing a wavelength bin size of ≈400 Å resolution for bluer bands and ≈500 Å for redder bands. SNfactory data consist of flux densities along a uniform grid of wavelengths. Because of this uniform spacing, we simply sum flux densities along the wavelength range defining our top-hat filters and then multiply said sum by the filter's wavelength range to calculate top-hat synthetic photometry:

Similarly, each corresponding variance spectrum is summed in quadrature to calculate synthetic photometry uncertainties.

For every observation, for the binned synthetic photometry a signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of at least SNR > 5 is required. It is also required that each SN Ia have at least eight separate days of observations. Where a single SN Ia has multiple spectra observed within a few hours, the weighted average of these flux values is used as a single effective observation. This decision was made to avoid introducing two timescales in the sampling of our light curves. Given the difficulty in constraining the date of maximum in SN Ia empirical models, we demand that there exist at least one observation two days before the SALT2 maximum phase. Furthermore, no SNe Ia with an observation gap greater than 4 days within a 4 day range before and after the SALT2 maximum are used. SN Ia light curves do not have significant structure less than 4 days, so gaps of this size or smaller have no discernible impact on our results. For consistency, the chosen maximum gap size of 4 days is the same as our fixed Gaussian process mean predictor (GPMP) length scale hyperparameter later described in Section 3. These cuts leave 80 SNe Ia in the training sample.

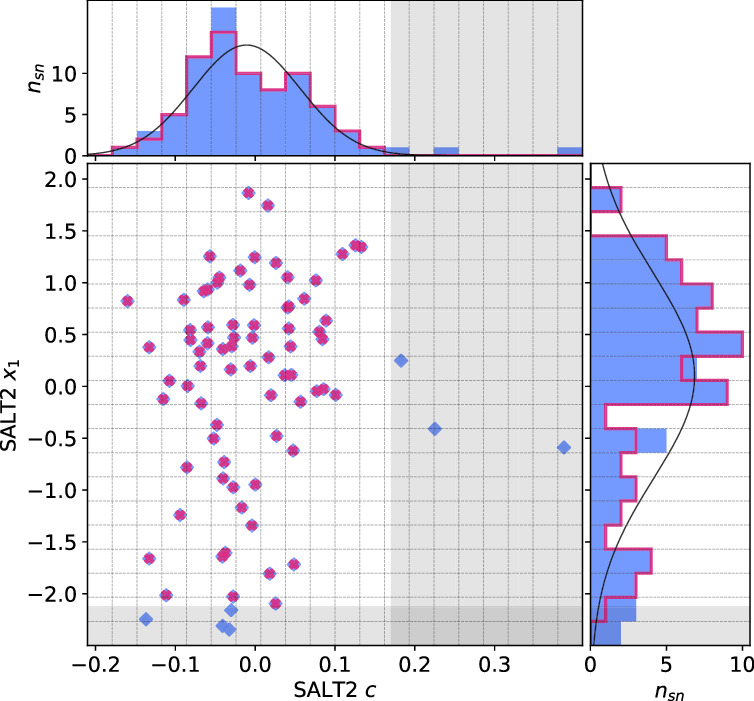

The distribution of SN Ia color parameters for any model is asymmetric due to the positive-definite nature of dust extinction (D. M. Scolnic et al. 2014; K. S. Mandel et al. 2017; D. Brout & D. Scolnic 2021). SN Ia stretch parameters such as SALT2's stretch proxy x1 are also best modeled with asymmetric distributions (D. M. Scolnic et al. 2014). We are interested in the Gaussian core of these distributions and partly “symmetrize” the data set by clipping the extended tails of our SALT2 c and x1 samples. Specifically, a 2σ clipping is done on each SALT2 c and x1 parameter sample in the direction each parameter's longer tail (Figure 1). The c clipping prevents heavily reddened SNe Ia from dominating the recovered dust-like behavior and obscuring the dust properties of the average SN Ia in training set—this c cut removes particularly reddened SNe Ia with peak apparent B − V > 0.18. The clipping is motivated by our interest in the core of the SN distribution that is used for cosmology, but comes at the expense of removing rarer objects that potentially provide more information on modeling SN Ia colors. A total of 73 SNe Ia remain after the SALT2 parameter σ clippings, consisting of 1155 individual spectra.

Figure 1. SALT2 c and x1 cuts to better capture a Gaussian “core” for training. The shaded regions correspond to 2σ clippings along the longer tail of each respective c and x1 distribution; blue points correspond to σ-clipped SNe.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageRelative to G. Aldering et al. (2020), and similar in spirit to K. Boone et al. (2021b), we remove spectra having poor extractions caused by SNR < 3; adjusting this threshold higher up to 10 did not affect our results. This step removes seven spectra, leaving 1148 to train the model.

3. Model

Global template parameters and per-SN parameters are differentiated by upper-case and lower-case characters, respectively. This model discretizes phase and wavelength space, using np = 16 phase nodes ranging from −16 ≤ tp,i ≤ 44 in 4 day intervals; as mentioned in Section 2, nλ = 10 with bins of constant R. Each phase-dependent template is an np × nλ matrix of parameter nodes, while each phase-independent template is a length-nλ vector.

The model prediction of the time-dependent spectral energy distribution evolution of an individual SN Ia is based on a temporal interpolation over a set of wavelength-dependent light curves at fixed phases Fλ,eff that are specific to that SN. The interpolation is controlled by a kernel K, which operates on Fλ,eff as shown in Equation (2). This equation is the same used to predict the mean in a Gaussian process, so we refer to this interpolation scheme as the GPMP:23

These GPMP kernel matrices K specifically are calculated with a stationary p = 2 Matérn covariance function C5/2 to ensure the interpolated curves are twice differentiable:

Fλ,eff is the light curve at wavelength λ on a grid of phase nodes; all nλ = 10 light curves form the flux node matrix Feff. tp,i ∈ tp is a vector indexing the model's np phase nodes and the per-SN parameter t0 aligns said SN Ia's observations with the model's phase grid. Intuitively, the first kernel matrix K in Equation (2) maps each observation to our phase node space after said observation phase ti is translated by t0, while the second accounts for Fλ,eff flux node covariance at grid phases tp,i and tp,j. GPMPs provide a natural framework to translate observed phase ti by the per-SN t0 parameter to the model grid's phase zero-point.

Note that t0 is not the fit date of maximum brightness—instead, t − t0 aligns the observation phase with the model's phase grid tp. As we train the model using rest-frame transformed spectrophotometry, each t0 is fit in its SN Ia's reference z = 0.05 frame. The kernel length scale hyperparameter ρ is fixed to match the phase node interval resolution of 4 days, although the model is insensitive to any reasonable choice in ρ (for example, ρ ≈ 1 week). Furthermore, by fixing ρ = 4, the matrix K is calculated and inverted only once during sampling. The uncertainty hyperparameter σ2 is fixed to unity since it is divided out in Equation (2).

The Feff of each SN is decomposed via element-wise multiplication (also called the Hadamard operation ∘) from a fiducial flux template matrix F0 and a warping matrix Ω:

F0 encodes the training sample's mean flux evolution via a set of fiducial light curves, while Ω encodes deviations from these fiducial light curves for a given SN Ia. Specifically, each column Ωλ of matrix Ω, for a given λ node, is defined as:

Mλ,1 is the λ-node column of the phase-dependent chromatic flux variation template matrix M1. M1 therefore encodes training sample light-curve variation. Lλ,1 and Lλ,2 are the λ-node elements of the two phase-independent chromatic flux variation template vectors L1 and L2, respectively (these appear as scalars in Equation (5) because of their phase independence). Each explicit per-SN parameter is contained within the warping template: the achromatic offset parameter χ0, the phase-dependent chromatic flux variation parameter s1, and the two phase-independent chromatic flux variation parameters c1 and c2. Both differences in intrinsic brightness and peculiar velocity effects are accounted for by the χ0 parameters.

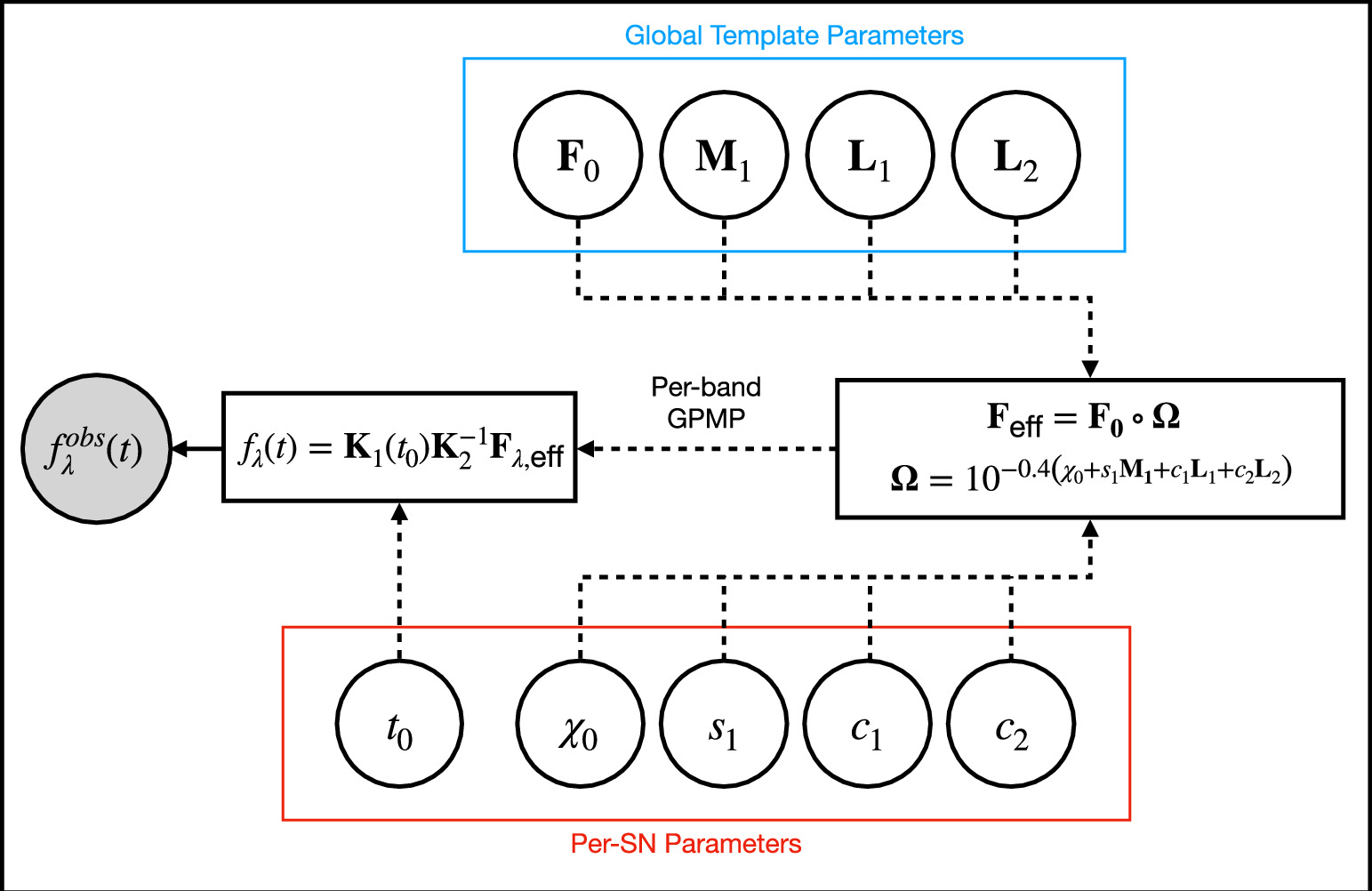

Figure 2 illustrates this model's architecture, specifically displaying the transformed phase-independent template basis  and

and  vectors later discussed in Section 3.3. Figure 3 is a directed acyclic graph of our model. Its conditional probability structure only connects observations to the model flux—deterministic connections (transformations and definitions) are presented with dashed arrows. Global template parameters are located in the top blue box and per-SN parameters in the bottom red box.

vectors later discussed in Section 3.3. Figure 3 is a directed acyclic graph of our model. Its conditional probability structure only connects observations to the model flux—deterministic connections (transformations and definitions) are presented with dashed arrows. Global template parameters are located in the top blue box and per-SN parameters in the bottom red box.

Figure 2. A schematic of our model's flux nodes. Each SN Ia has an effective flux node matrix Feff that is an element-wise product of the sample's fiducial flux template F0 and a warping matrix Ω. This warping matrix includes the phase-dependent chromatic flux variation template M1, two phase-independent chromatic flux variation templates  and

and  (which make up the 2D phase-independent chromatic variation model), and per-SN parameters χ0 (achromatic offset), s1 (phase-dependent chromatic flux variation contribution), and c1 and c2 (phase-independent chromatic flux template contributions). Presented here are the

(which make up the 2D phase-independent chromatic variation model), and per-SN parameters χ0 (achromatic offset), s1 (phase-dependent chromatic flux variation contribution), and c1 and c2 (phase-independent chromatic flux template contributions). Presented here are the  and

and  basis representation of the phase-independent templates (see Section 3.3 for more information). Per-band nodes are presented in this plot having the same figure color.

basis representation of the phase-independent templates (see Section 3.3 for more information). Per-band nodes are presented in this plot having the same figure color.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageFigure 3. A directed acyclic graph representation of our model. Per-SN model parameters are located in the bottom red box; global template parameters are in the top blue box. The dashed arrows are deterministic relations (transformations and definitions). The only explicit conditional probability in the model's architecture relates observations  to modeled flux fλ(t). We use GPMP interpolation per band in mapping effective template nodes Feff nodes to a predicted flux fλ(t).

to modeled flux fλ(t). We use GPMP interpolation per band in mapping effective template nodes Feff nodes to a predicted flux fλ(t).

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution image3.1. Template Constraints and Per-supernova Parameter Models

The third λ band, tp,i = 0 phase node of F0 is fixed to 1—it is referred to here as fixed band 3 and corresponds to the wavelength node at 4084 Å, the top-hat filter band closest to a standard B-band. This constraint prevents any scaling degeneracy between F0 and the model's χ0 parameter while also setting the specific phase node that the t0 parameter aligns observations to. Physical consideration further requires all F0 flux node parameters be bound to greater than or equal 0, so we enforce nonnegative values for all flux values.

All chromatic flux variation templates L1, L2, and M1 have scaling degeneracies with their respective per-SN parameters c1, c2, and s1. For example, the transformations s1 → s1/α and M1 → αM1 leave the model unchanged; identical degeneracies exist for c1–L1 and c2–L2. Each scaling degeneracy is removed by requiring these three templates be normalized. This is a straightforward procedure for L1 and L2, where each is instantiated in Stan as unit vectors, but a more involved process is used to normalize the template matrix M1. We first define a unit vector of length np × nλ that is then transformed into M1 by “chopping” said unit vector into nλ column vectors (each of length np) that form the column space of a now normalized M1.24 No further constraints or bounds are placed on the template parameters.

Zero-mean constraints are placed on the per-SN parameter sets c1, c2, and s1. A reference SN Ia could be selected to serve as the c1, c2, and s1 zero-points, but we opt instead to require these per-SN parameter sets to always have a mean of 0. These constraints are enforced structurally by instantiating these parameter sets as centered vectors (Appendix A).

3.2. Fitting the Model

As described in, e.g., C. Saunders et al. (2018) and D. Rubin et al. (2022), the SNfactory data are extracted from the 15 × 15 spaxels of the SNIFS (G. Aldering et al. 2002; B. Lantz et al. 2004) that are projected as spectra onto 2000 × 4000 CCD detectors. In this extraction process the Poisson noise and the readout noise for each pixel are included with appropriate weights. The host galaxy is subtracted from this data cube using a reference data cube taken more than 1 yr later, as described in S. Bongard et al. (2011). Gray dimming by clouds is corrected as described in R. Pereira et al. (2013). The remaining SN-only light is fit with a point-spread function (PSF) model, as described in C. Buton et al. (2013) and D. Rubin et al. (2022), again propagating the Poisson and detector noise uncertainties. Due to small unmodeled PSF shape variations, there is additional uncertainty, which is empirically determined to be approximately 3% (P. F. Léget et al. 2020). The final calculated uncertainties are dominated either by this PSF shape noise or the Poisson plus detector noise.

Initial trial runs confirmed that the nominal uncertainties were underestimated, not having included galaxy-subtraction errors, and that the overall distribution had broader tails than a normal distribution. We thus added a further uncertainty equal to 2% of each SN Ia's maximum observed flux and treat measurement uncertainties as having a Cauchy distribution, which led to stable convergence of the fit. The credibility of this ansatz was checked though inspection of the pull distribution of photometric residuals around the final best fit. This approach has previously been used to represent model uncertainty in B. M. Rose et al. (2021).

The first source of error preferentially increases the high-flux observational errors, while the second largely affects low-flux observations, particularly those 20 or more days after peak brightness. All added uncertainties are diagonal: no covariance is injected into our data before training.

The nominal SNfactory measurement and uncertainty are used as the Cauchy distribution location and scale. For each flux observation  with its corresponding measurement uncertainty

with its corresponding measurement uncertainty  , our likelihood function takes the form:

, our likelihood function takes the form:

No correlations are added between measurement errors.

The model is implemented and trained using the statistics programming language Stan (B. Carpenter et al. 2017). Built into Stan is a No U-Turns (NUTS) Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (HMC) sampler well suited for sampling our model's high-dimensional posterior. No explicit priors are placed on the templates or per-SN parameter sets, instead leaving them with default implicit flat priors along any aforementioned bounds (Section 3.1).

Stan is informed with initial conditions estimated by first running simpler versions of the model. We do this only to improve sampling efficiency—it is not necessary for our model's convergence. This process is done iteratively, starting with the simplest model that only obtains the t0, F0, and χ0 parameters (a mean light-curve model). The results of this simplest model then become the initial conditions for a more complex model that includes the L1 and c1 parameters. Other components (specifically, L2 and c2, and then M1 and s1) are then added and trained using the prior model iteration's fit as initial conditions until all the described model's components are incorporated. Note that we use SALT2's  as initial conditions for the t0 parameters when training the simplest of these models.

as initial conditions for the t0 parameters when training the simplest of these models.

With Stan's default NUTS we pull 4000 samples for each of 16 types of instantiated samplers: 2000 warm-up followed by 2000 samples iterations per chain. Stan is run on the University of Pittsburgh's Computational Resource Center.25

The convergence metrics “split- ” and “effective sample size” were calculated after postprocessing using techniques provided in A. Vehtari et al. (2021). After training and postprocessing, each SN Ia is refit with the template parameters fixed (F0, M1, L1, and L2) to determine the final values for the per-SN Ia χ0, s1, c1, and c2, permitting a direct comparison of these per-SN parameters against other empirical SN Ia models.

” and “effective sample size” were calculated after postprocessing using techniques provided in A. Vehtari et al. (2021). After training and postprocessing, each SN Ia is refit with the template parameters fixed (F0, M1, L1, and L2) to determine the final values for the per-SN Ia χ0, s1, c1, and c2, permitting a direct comparison of these per-SN parameters against other empirical SN Ia models.

There is no selected standard ΔMB = 0 SN Ia identified in the training sample, leaving a nontrivial linear degeneracy between the achromatic offset parameter χ0 and phase-independent parameters c1 and c2. For physical reasons, c1 and c2 should not correlate with the intrinsic magnitude, which ideally should only be captured by χ0.

Linear transformations from P. F. Léget et al. (2020) are used to remove correlations between both the c1 and χ0 parameters, and the c2 and χ0 parameters, as summarized in Appendix B. Implementing this directly in the Stan model leaves the results unchanged but does reduce the sampling efficiency, so this step is performed after sampling.

3.3. Interpreting the Phase-independent Templates

Each sampler from Stan explores a plane spanned by the template vectors L1 and L2.26

Even after decorrelating χ0 from c1 and c2, the output basis {L1, L2} is not unique, a consequence of this model's physics-agnostic architecture. This is because for any nonsingular linear transformation the output basis vectors (i.e., aL1 + bL2 and cL1 + dL2 for  and ab − cd ≠ 0) necessarily span the aforementioned plane. To quantify this plane's convergence (as opposed to only its basis vectors), for each posterior sample we calculate a bivector

and ab − cd ≠ 0) necessarily span the aforementioned plane. To quantify this plane's convergence (as opposed to only its basis vectors), for each posterior sample we calculate a bivector  that, by definition, spans the plane of interest. Importantly, the bivector representation

that, by definition, spans the plane of interest. Importantly, the bivector representation  is no longer ambiguous.

is no longer ambiguous.

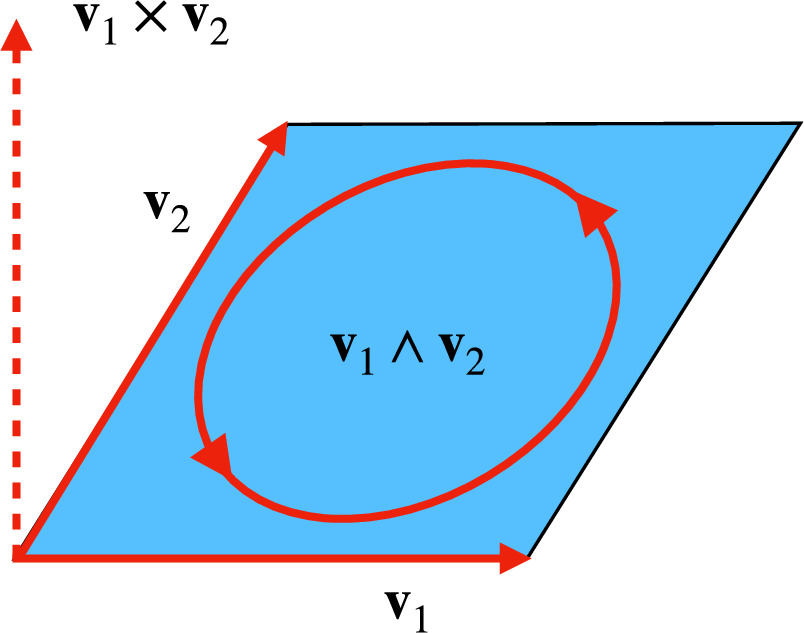

A bivector is a geometric object representing an oriented plane element constructed from the wedge product (see Figure 4 for an illustration). Intuitively, a bivector corresponds to a plane like a vector corresponds to a line, and the wedge product is the dual to a cross product in 3D. Unlike the cross product, the wedge product generalizes to any finite-dimensional vector space greater than 2, meaning bivectors are well-defined in this model's 10D wavelength node space. Now any SN Ia'a phase-independent chromatic flux variation curve c = c1L1 + c2L2 can be interpreted as residing in the plane spanned by  , regardless of the selected L1, L2 basis.

, regardless of the selected L1, L2 basis.

Figure 4. This is an illustration of a bivector (the blue parallelogram) v1 ∧ v2 constructed by the vectors v1 and v2 (the red vectors) in 3D. A 3D space allows for the corresponding cross product to be included for reference (the red dashed vector). Bivectors, like vectors, are oriented objects, with the bivector v1 ∧ v2 having a counterclockwise orientation determined by component vector ordering (here represented with an oriented red loop). Reversing the product order reverses a bivector's “circulation” or orientation: v2 ∧ v1 = −v1 ∧ v2. Note that the cross product does not generalize to all finite-dimensional vector spaces, while the wedge product ∧ does.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageEach component of the bivector  is calculated as follows:

is calculated as follows:

where  is the ith wavelength component of template L1 and

is the ith wavelength component of template L1 and  is the ith wavelength component of template L2. Importantly, this representation is independent of the L1, L2 choice. Note that

is the ith wavelength component of template L2. Importantly, this representation is independent of the L1, L2 choice. Note that  is normalized so as to represent a unit plane element. With these transformed parameters

is normalized so as to represent a unit plane element. With these transformed parameters  , the model can unambiguously be tested for convergence and the best-fit templates be determined.

, the model can unambiguously be tested for convergence and the best-fit templates be determined.

3.4. Bases for the Phase-independent Chromatic Variation Model

We now seek a pair of vectors, L1 and L2, that span  and readily provide insight into the physical origin of the model's 2D phase-independent chromatic flux model. Two such bases are considered.

and readily provide insight into the physical origin of the model's 2D phase-independent chromatic flux model. Two such bases are considered.

3.4.1. Maximum Variance Ratio Basis

The first basis, called the maximum variance ratio (MVR)27 basis, is derived directly from the corresponding c1–c2 distribution.

New and uncorrelated parameter sets  and

and  with their relative variances maximized are found via a linear transformation. The result is a basis for

with their relative variances maximized are found via a linear transformation. The result is a basis for  where

where  accounts for the most chromatic flux diversity by a single template in

accounts for the most chromatic flux diversity by a single template in  , while

, while  captures any remaining variation. This basis amounts to the assumption that two independent physical effects affect chromatic flux variation (e.g., the amount of dust or intrinsic SN Ia diversity) while designating as much of the variance as possible to one source (e.g., dust). This assumption provides some useful insights even if it does not totally satisfy our physical expectations, as it does not consider additional possible effects (e.g., the kind of dust), nor that SNe and their progenitor environments likely correlate with said effects. This basis's solution is found by numeric minimization; it is not orthogonal.

captures any remaining variation. This basis amounts to the assumption that two independent physical effects affect chromatic flux variation (e.g., the amount of dust or intrinsic SN Ia diversity) while designating as much of the variance as possible to one source (e.g., dust). This assumption provides some useful insights even if it does not totally satisfy our physical expectations, as it does not consider additional possible effects (e.g., the kind of dust), nor that SNe and their progenitor environments likely correlate with said effects. This basis's solution is found by numeric minimization; it is not orthogonal.

The MVR basis is determined as follows. A basis centered at the origin can be described by the angle between the unit vectors and their orientation. Starting with an orthogonalized output basis from Stan ![${\boldsymbol{L}}=[{{\boldsymbol{L}}}_{1}^{\,\rm{orth}\,},{{\boldsymbol{L}}}_{2}^{\,\rm{orth}\,}]$](https://content.cld.iop.org/journals/0004-637X/982/2/110/revision1/apjad9f32ieqn28.gif) for

for  and a per-SN coefficient matrix c (here arranged as an nsn × 2 matrix), adding an extra angle θ between the basis is achieved with the transformation:

and a per-SN coefficient matrix c (here arranged as an nsn × 2 matrix), adding an extra angle θ between the basis is achieved with the transformation:

In this  basis, the per-SN coefficients

basis, the per-SN coefficients  have an orientation given by VT from the singular value decomposition (SVD) of

have an orientation given by VT from the singular value decomposition (SVD) of  . Taking VTM and normalizing its rows to be unit vectors gives the properly oriented basis given θ. Note that these primed components here are unrelated to those introduced below.

. Taking VTM and normalizing its rows to be unit vectors gives the properly oriented basis given θ. Note that these primed components here are unrelated to those introduced below.

For this basis, the ellipticity of its corresponding c distribution is again found using SVD, given by  . An optimizer is used to determine the θ that maximizes the ellipticity.

. An optimizer is used to determine the θ that maximizes the ellipticity.

3.4.2. Cardelli–Clayton–Mathis-derived Basis

We also desire a basis that readily separates rapidly changing chromatic flux variation (i.e., that akin to SN absorption/emission features) from continuum-like chromatic flux variation (i.e., dust-like behavior). This continuum-like variation is assumed to be dust-like, given dust extinction's ubiquitous contribution to SN Ia color/chromatic flux variation. The two phase-independent plots found in Figure 2 provide an example of what we want from this basis—specifically, one template being more smooth with respect to wavelength than the other.

For the second basis, the vector  simultaneously resides within the planes spanned by both

simultaneously resides within the planes spanned by both  and the Cardelli–Clayton–Mathis (CCM89) dust model (J. A. Cardelli et al. 1989), defining the first basis component. This intersection ensures it captures smooth, CCM89-like chromatic variability. The other basis vector

and the Cardelli–Clayton–Mathis (CCM89) dust model (J. A. Cardelli et al. 1989), defining the first basis component. This intersection ensures it captures smooth, CCM89-like chromatic variability. The other basis vector  is chosen to be perpendicular to

is chosen to be perpendicular to  , while still residing in the

, while still residing in the  plane; this basis is orthogonal by construction. Note that

plane; this basis is orthogonal by construction. Note that  will not necessarily be perpendicular to the plane spanned by CCM89, but is still guaranteed to provide the least continuum-like variability with respect to (w.r.t.) wavelength (and therefore, the most spectral-feature-like behavior) allowed by

will not necessarily be perpendicular to the plane spanned by CCM89, but is still guaranteed to provide the least continuum-like variability with respect to (w.r.t.) wavelength (and therefore, the most spectral-feature-like behavior) allowed by  . This basis provides a useful representation not because it recovers a mathematically valid dust extinction curve, but instead because it clearly separates rapidly changing chromatic flux variation from SN continuum-like variability. It is important to remember that intrinsic variability could still affect the direction of the first basis vector

. This basis provides a useful representation not because it recovers a mathematically valid dust extinction curve, but instead because it clearly separates rapidly changing chromatic flux variation from SN continuum-like variability. It is important to remember that intrinsic variability could still affect the direction of the first basis vector  , which means this basis does not guarantee a physical decomposition into exclusive dust and intrinsic components. As such, any dust-like properties inferred from L1 in isolation are physically ambiguous.

, which means this basis does not guarantee a physical decomposition into exclusive dust and intrinsic components. As such, any dust-like properties inferred from L1 in isolation are physically ambiguous.

The CCM89-derived basis is calculated as follows. Since CCM89 has two basis curves a(λ) and b(λ) (one for each parameter AV and AV/RV, respectively), one can construct a CCM89 unit bivector  from discretized curves a(λ) → a and b(λ) → b using an appropriately modified version of Equation (7):

from discretized curves a(λ) → a and b(λ) → b using an appropriately modified version of Equation (7):  and

and  . The two planes spanned by

. The two planes spanned by  and

and  then intersect within the nλ-dimensional wavelength vector space along a line. It is the vector which spans this intersecting line that defines the new

then intersect within the nλ-dimensional wavelength vector space along a line. It is the vector which spans this intersecting line that defines the new  template:

template:

We are free to choose a new L2 as long as it resides within the subspace represented by  . To minimize this L2 template's dust-like properties,

. To minimize this L2 template's dust-like properties,  is defined as a θ = π/2 radian rotation of

is defined as a θ = π/2 radian rotation of  within the plane spanned by

within the plane spanned by  via a rotation operator

via a rotation operator  :

:

This rotation maximizes the component of  that is perpendicular to the plane spanned by

that is perpendicular to the plane spanned by  . The new

. The new  also transforms the c1 and c2 parameters sets, here labeled

also transforms the c1 and c2 parameters sets, here labeled  and

and  .

.

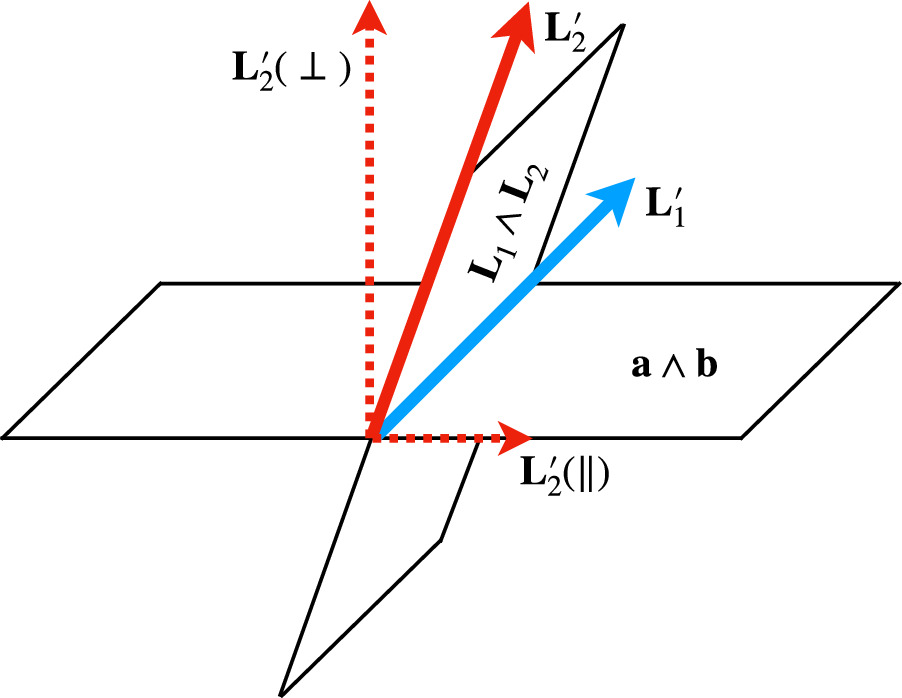

Figure 5 provides a 3D view of the geometric intuition involved in finding the CCM89-derived basis. All calculations discussed here are implemented using geometric algebra, which provides a novel approach to study oriented subspaces. Geometric algebraic implementations for calculating intersections, projections, and rotation operations are summarized in Appendix C. Although we exploit geometric algebra's elegance and interpretability to perform all said operations, each operation could be done using more classical linear algebraic techniques if desired.

Figure 5. A 3D representation the CCM89 basis's geometric intuition. The blue solid vector is the transformed  template spanning the intersection of two planes, one spanned by the model bivector

template spanning the intersection of two planes, one spanned by the model bivector  and the other spanned by the CCM89 bivector

and the other spanned by the CCM89 bivector  . The red solid vector is a π/2 rotation in the plane spanned by

. The red solid vector is a π/2 rotation in the plane spanned by  that defines the transformed

that defines the transformed  template. The decomposition

template. The decomposition  with respect to the CCM89 plane spanned by

with respect to the CCM89 plane spanned by  is given with the red dashed arrows.

is given with the red dashed arrows.

Download figure:

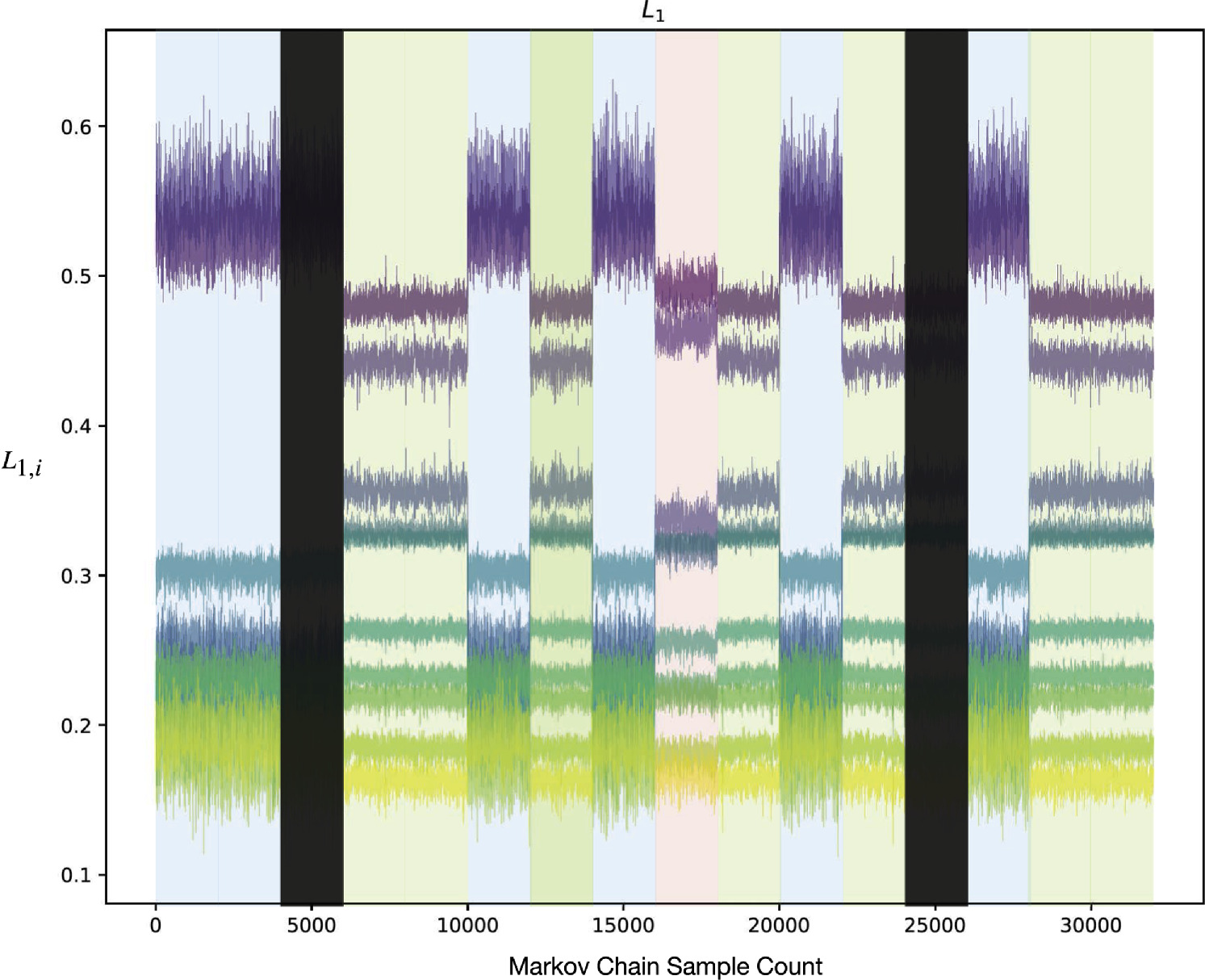

Standard image High-resolution image3.5. Handling Similar Solutions

In training, the samplers converge to one of three sets of very similar solutions, as is apparent in the per-chain values of L1 shown in Figure 17. We find that simultaneously obtaining global template and per-SN parameters leaves the resulting samplers sensitive to the three least representative SNe Ia in the training sample (based on residuals). These groups are associated with slightly different solutions for these three SNe Ia, as seen by eye and quantitatively through their χ0 solutions. Consider the following analogy: consider the inertia tensor of a space station as being the model's global templates and the coordinates of its crew members corresponding to the per-SN parameters. The moment of inertia changes only slightly if crew members move to another location on the station (assuming the space station is much more massive than the crew's total weight). Similarly, it is this “change in position” of per-SN solutions that is causing a very subtle change in template parameters, preventing complete convergence. Obviously this is not a fair comparison, but the resulting effects are very similar, hence this comparison.

The worst performing SN Ia PTF11mkx consistently sees a 1σ difference between χ0 values between different chain groups—considering that this χ0 parameter fit uncertainty is only ≈1%, this tail wagging is very subtle. Indeed, when refitting per-SN parameters with one of the group solutions as a fixed global template (Section 4.4), all chains converge to the same solutions for the three SNe Ia. Similarly, if two different group solutions are separately held constant and refit individually, the two resulting per-SN parameter sets are indistinguishable. Because each group's solutions are consistently very similar, we opt to use the weighted average of all solutions for the best-fit template. This decision to use an average of all groups, as opposed to using a specific solution, has no impact on the remaining analysis.

Note that refitting with a fixed t0 parameter does not prevent this subtle grouping, nor does cutting these three SNe Ia from the training set. If these three aforementioned troublesome SNe Ia are removed, the next few SNe Ia that are the least representative of this newly trimmed sample start “wagging.” This instability may be a feature of our model. In particular, the flat priors we use for the c1 and c2 distributions may bias the results for the least representative SNe Ia of a given training sample. Considering that global template parameters again were effectively unchanged with their removal, we retain those three SNe Ia for the remainder of the analysis.

4. Best-fit Model Results

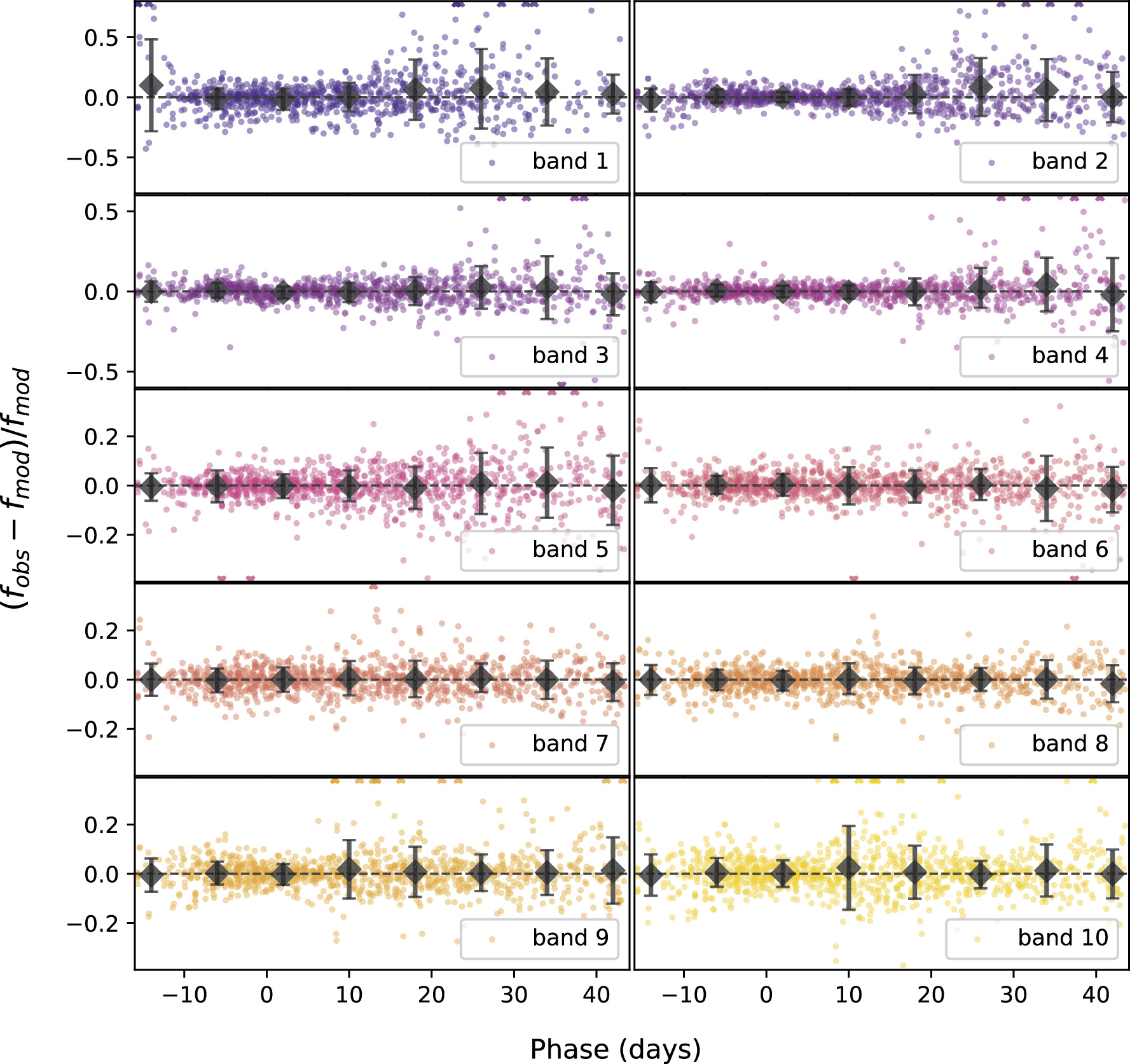

Our model, as implemented with Stan, consists of global template parameters and per-SN parameters. We define the best-fit solution to be the mode of a 365D template parameter space,28 with each per-SN parameter marginalized before estimating from HMC sampling the posterior's maximum. This mode is estimated using a mean shift clustering algorithm implemented in the scikit-learn package using the default flat kernel (F. Pedregosa et al. 2011). To estimate a consistent best-fit solution, bivector components L = L1 ∧ L2 (Equation 7) are used instead of the L1 and L2 components directly. This process is analogous to maximum a posteriori estimation of the HMC-sampled posterior, but allows first for the aforementioned postprocessing. The marginal posterior dispersion for each parameter is presented as 68th percentile error bars. The residuals of the best-fit model, alongside binned averages, are presented in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Best-fit model residuals with respect to observations presented for each of our 10 bands. Eight day binned averages for each band are presented as black diamonds, with error bars being binned standard deviations. The carets at the top and bottom edges represent points that lie outside the range of the plots.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageTwo of the 16 HMC samplers were rejected after fitting because (1) their resulting mean t0 parameter values were systematically inconsistent by 4 to 5 days with SALT2 date of maximum, 2) the corresponding light-curve shapes were nonphysical, and (3) these two samplers have notably inconsistent  values relative to the 14 retained samplers. The 14 remaining samplers converge to three very similar group solutions of which the weighted average is taken; see Section 3.5 for more details.

values relative to the 14 retained samplers. The 14 remaining samplers converge to three very similar group solutions of which the weighted average is taken; see Section 3.5 for more details.

Table 1 provides the median values and 68th percentile upper and lower values for the per-SN light-curve model parameters.

4.1. Phase-independent Chromatic Flux Variation Templates

Ostensibly, if  were to only capture CCM89 dust-like behavior, then the planes spanned by

were to only capture CCM89 dust-like behavior, then the planes spanned by  and

and  would be effectively parallel and any intersection poorly constrained. This turns out to not be the case, with the best-fit solution recovering a planar separation angle of about 80∘.

would be effectively parallel and any intersection poorly constrained. This turns out to not be the case, with the best-fit solution recovering a planar separation angle of about 80∘.

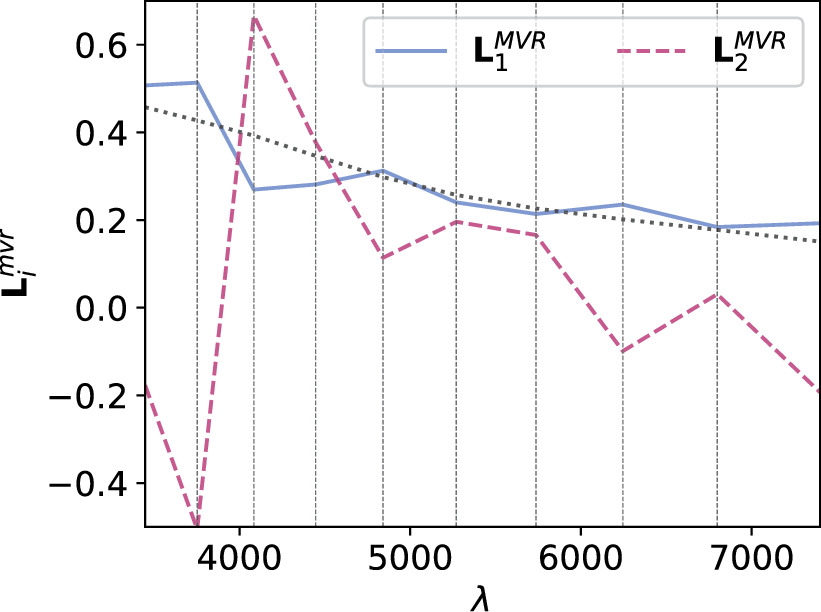

4.1.1. Maximum Variance Ratio Basis

Figure 7 presents the MVR basis as described in Section 3.4. Qualitatively,  appears nominally more dust-like than its counterpart

appears nominally more dust-like than its counterpart  . Figure 7 includes the best-fit CCM89 curve

. Figure 7 includes the best-fit CCM89 curve  for reference, showcasing that its most extreme divergence from CCM89 is blueward of 5000 Å.

for reference, showcasing that its most extreme divergence from CCM89 is blueward of 5000 Å.  , on the other hand, captures variation that is not readily describable as dust-like: normal dust extinction should be absorptive across the optical wavelength range whereas the sign flip in

, on the other hand, captures variation that is not readily describable as dust-like: normal dust extinction should be absorptive across the optical wavelength range whereas the sign flip in  produces simultaneous brightening/dimming on either side of 4000 Å. Although the degree of variation increases as wavelength decreases, there is a distinct flip in behavior around 4000 Å. Such behavior is inconsistent with dust extinction.

produces simultaneous brightening/dimming on either side of 4000 Å. Although the degree of variation increases as wavelength decreases, there is a distinct flip in behavior around 4000 Å. Such behavior is inconsistent with dust extinction.

Figure 7. The blue solid line corresponds to the first MVR component  , which appears nominally more consistent with dust-like variation than its counterpart

, which appears nominally more consistent with dust-like variation than its counterpart  , given as the magenta dashed.

, given as the magenta dashed.  has a best-fit

has a best-fit  given as the gray dotted line, with most of its divergence from a CCM89 curve occurring blueward of 5000 Å.

given as the gray dotted line, with most of its divergence from a CCM89 curve occurring blueward of 5000 Å.  captures variation not readily describable as dust-like.

captures variation not readily describable as dust-like.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageThe conditions for the target parameter set distributions are to assign maximum variance to one component while keeping the second component uncorrelated. These conditions yield a basis consistent with the expectation that dust-like variation is the primary contributor to SN Ia phase-independent chromatic flux variation while intrinsic SN Ia diversity uncorrelated with dust accounts for additional variability.

4.1.2. Cardelli–Clayton–Mathis-derived Basis

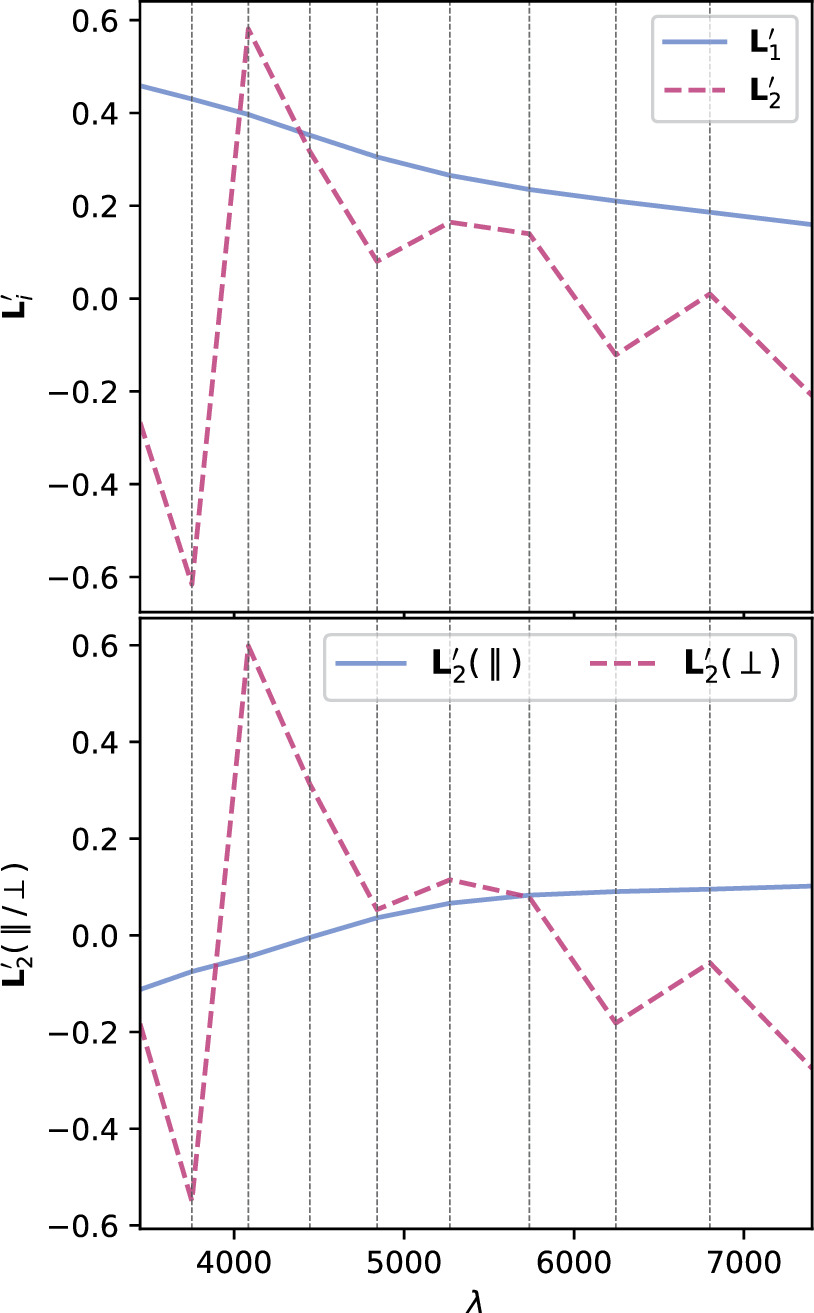

The template  is presented in the top plot of Figure 8. As summarized in Section 3.4, the intersection of the plane spanned by

is presented in the top plot of Figure 8. As summarized in Section 3.4, the intersection of the plane spanned by  with the plane spanned by

with the plane spanned by  defines the first phase-independent chromatic flux template

defines the first phase-independent chromatic flux template  . This

. This  template, as expected, captures continuum-like variation akin to dust extinction.

template, as expected, captures continuum-like variation akin to dust extinction.

Figure 8. The top plot presents phase-independent chromatic flux variation templates  and

and  .

.  has a recovered total-to-selective extinction of

has a recovered total-to-selective extinction of  . The bottom plot presents a decomposition of

. The bottom plot presents a decomposition of  into its parallel and perpendicular components with respect to the CCM89 plane.

into its parallel and perpendicular components with respect to the CCM89 plane.  clearly captures some dust-like variability, despite being dominated by intrinsic modes. Although the low-resolution wavelength binning prevents quantification of spectral features, the most impressive

clearly captures some dust-like variability, despite being dominated by intrinsic modes. Although the low-resolution wavelength binning prevents quantification of spectral features, the most impressive  variability appears in the Ca ii H and K regime.

variability appears in the Ca ii H and K regime.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageFrom  we find an intersection total-to-selective extinction ratio of

we find an intersection total-to-selective extinction ratio of  . As mentioned in 3.4, this RV is not immediately physically interpretable without an AV model.

. As mentioned in 3.4, this RV is not immediately physically interpretable without an AV model.

Also presented in the top plot of Figure 8 is template  . Unlike

. Unlike  ,

,  captures the more rapidly changing flux variability allowable by

captures the more rapidly changing flux variability allowable by  . Specifically, L2 is capturing wavelength variation at scales smaller than that expected by continuum dust variability, at least within the optical regime. Indeed, its features nominally align with spectral features. Also note the similarity between

. Specifically, L2 is capturing wavelength variation at scales smaller than that expected by continuum dust variability, at least within the optical regime. Indeed, its features nominally align with spectral features. Also note the similarity between  and

and  despite their vastly different constructions.

despite their vastly different constructions.

is not perpendicular to the CCM89 plane because the plane spanned by

is not perpendicular to the CCM89 plane because the plane spanned by  is itself not perpendicular. As such,

is itself not perpendicular. As such,  also captures a dust-like component alongside its dominating spectral-like component. The bottom panel presents this template's decomposition into parallel and perpendicular components defined with respect to CCM89's plane for reference.

also captures a dust-like component alongside its dominating spectral-like component. The bottom panel presents this template's decomposition into parallel and perpendicular components defined with respect to CCM89's plane for reference.

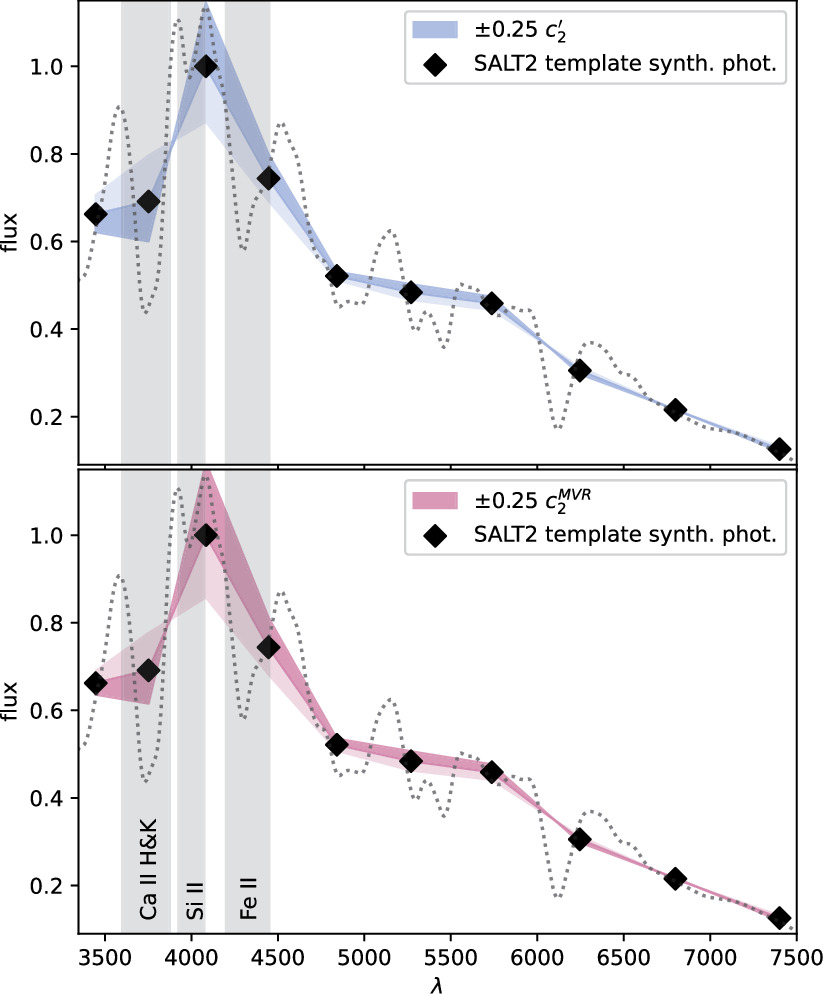

4.1.3. Intrinsic Variation

Both of the best-fit template representations  and

and  capture pronounced phase-independent chromatic flux variation blueward of 4500 Å that is inconsistent with dust (see Figure 9). Indeed, no extrinsic phenomena readily describe this behavior. Variation blueward of 4500 Å includes the prominent Ca ii H and K feature and its Si iii counterpart, Si ii λ4130, C ii λ4267, Fe ii λ4404, and Mg ii λ4481. With our choice of splitting the spectral range into nλ = 10 synthetic filters, the model cannot completely distinguish between said features, although at least one node for both

capture pronounced phase-independent chromatic flux variation blueward of 4500 Å that is inconsistent with dust (see Figure 9). Indeed, no extrinsic phenomena readily describe this behavior. Variation blueward of 4500 Å includes the prominent Ca ii H and K feature and its Si iii counterpart, Si ii λ4130, C ii λ4267, Fe ii λ4404, and Mg ii λ4481. With our choice of splitting the spectral range into nλ = 10 synthetic filters, the model cannot completely distinguish between said features, although at least one node for both  and

and  and their corresponding variation seemingly align with the wavelength bin where Ca ii H and K is the dominant contributor to a strong spectral feature; Si ii and Fe ii features also contribute to this variation. Hints of chromatic flux variability ostensibly aligns with the SNe Ia signature Si ii λ6347 feature and O i λ7774, which are visible in Figure 8, but in practice do not affect any resulting model flux predictions (again, see Figure 9).

and their corresponding variation seemingly align with the wavelength bin where Ca ii H and K is the dominant contributor to a strong spectral feature; Si ii and Fe ii features also contribute to this variation. Hints of chromatic flux variability ostensibly aligns with the SNe Ia signature Si ii λ6347 feature and O i λ7774, which are visible in Figure 8, but in practice do not affect any resulting model flux predictions (again, see Figure 9).

Figure 9. This figure demonstrates a ± 0.2 mag c2 variation (blue for the CCM89 basis  , maroon for

, maroon for  ) of

) of  overlaid on SALT2's mean template t = 0 phase spectrum (dashed black line). The spectrum is binned via synthetic photometry with top-hat filters, presented as black diamonds. Flux units are normalized by synthetic photometry wavelength 4048 Å value to unity and example spectral features blueward of 4500 Å are presented for reference.

overlaid on SALT2's mean template t = 0 phase spectrum (dashed black line). The spectrum is binned via synthetic photometry with top-hat filters, presented as black diamonds. Flux units are normalized by synthetic photometry wavelength 4048 Å value to unity and example spectral features blueward of 4500 Å are presented for reference.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageWe use the same data set used by C. Saunders et al. (2018) for their SNEMO analysis. Comparing both  and

and  to SNEMO2 and SNEMO7 eigenvectors (with two and seven components, respectively) yields indecisive insight, though. Figure 6 from C. Saunders et al. (2018) shows SNEMO eigenvectors describing similar

to SNEMO2 and SNEMO7 eigenvectors (with two and seven components, respectively) yields indecisive insight, though. Figure 6 from C. Saunders et al. (2018) shows SNEMO eigenvectors describing similar  or

or  behavior at maximum, but all of these eigenvectors are clearly phase dependent—no eigenvector's evolution seems approximately phase independent. Figures 9 through 12 from C. Saunders et al. (2018) present some unexplained variation for SNEMO2 blueward of 4500 Å that is nominally phase independent up to 6 days postmaximum; this all but disappears with SNEMO7. That SNEMO2, itself similar to SALT2, sees unexplained phase-independent variability around maximum that aligns with the

behavior at maximum, but all of these eigenvectors are clearly phase dependent—no eigenvector's evolution seems approximately phase independent. Figures 9 through 12 from C. Saunders et al. (2018) present some unexplained variation for SNEMO2 blueward of 4500 Å that is nominally phase independent up to 6 days postmaximum; this all but disappears with SNEMO7. That SNEMO2, itself similar to SALT2, sees unexplained phase-independent variability around maximum that aligns with the  and

and  features seems indicative of our model's performance, but such a claim taken alone is likely an excessive interpretation.

features seems indicative of our model's performance, but such a claim taken alone is likely an excessive interpretation.

SNfactory data are also used by K. Boone et al. (2021b) with their Twins Embedding nonlinear model. More interesting insight is gained in comparing their findings with our template representations  and

and  , since Twins Embedding is currently a phase-independent, maximum-phase model. Blueward of 4500 Å, spectral variation recovered by Twins Embedding loosely aligns with the both

, since Twins Embedding is currently a phase-independent, maximum-phase model. Blueward of 4500 Å, spectral variation recovered by Twins Embedding loosely aligns with the both  and

and  templates (see Figures 4, 6, and 10 from K. Boone et al. 2021a for reference). Recovering this consistent variation in our phase-independent template, albeit at lower wavelength bin resolution, lends credibility that

templates (see Figures 4, 6, and 10 from K. Boone et al. 2021a for reference). Recovering this consistent variation in our phase-independent template, albeit at lower wavelength bin resolution, lends credibility that  as a whole is capturing intrinsic variation.

as a whole is capturing intrinsic variation.

Past analyses by D. Branch et al. (1993) and A. G. Riess et al. (1998b) find Ca ii H and K features are relatively stable in the week before and weeks after peak B-band brightness, with this effective phase independence being sufficiently stable to exploit for the latter's “snapshot” methodology from which they constrain luminosity distances. Both  basis representations do capture intrinsic, phase-independent variation around Ca ii H and K, but this alone is not profound evidence of fundamental Ca ii H and K time independence in the SN Ia population. SN Ia Ca ii H and K features, as with all spectral features, demonstrably evolve with time. In its current form, this model cannot distinguish between phase-averaged spectral variation or truly phase-independent intrinsic variation. Indeed, a goal of this project is to demonstrate that intrinsic chromatic flux variation can “leak” into phase-independent components, something that is occurring in these results.

basis representations do capture intrinsic, phase-independent variation around Ca ii H and K, but this alone is not profound evidence of fundamental Ca ii H and K time independence in the SN Ia population. SN Ia Ca ii H and K features, as with all spectral features, demonstrably evolve with time. In its current form, this model cannot distinguish between phase-averaged spectral variation or truly phase-independent intrinsic variation. Indeed, a goal of this project is to demonstrate that intrinsic chromatic flux variation can “leak” into phase-independent components, something that is occurring in these results.

4.2. Fiducial Template

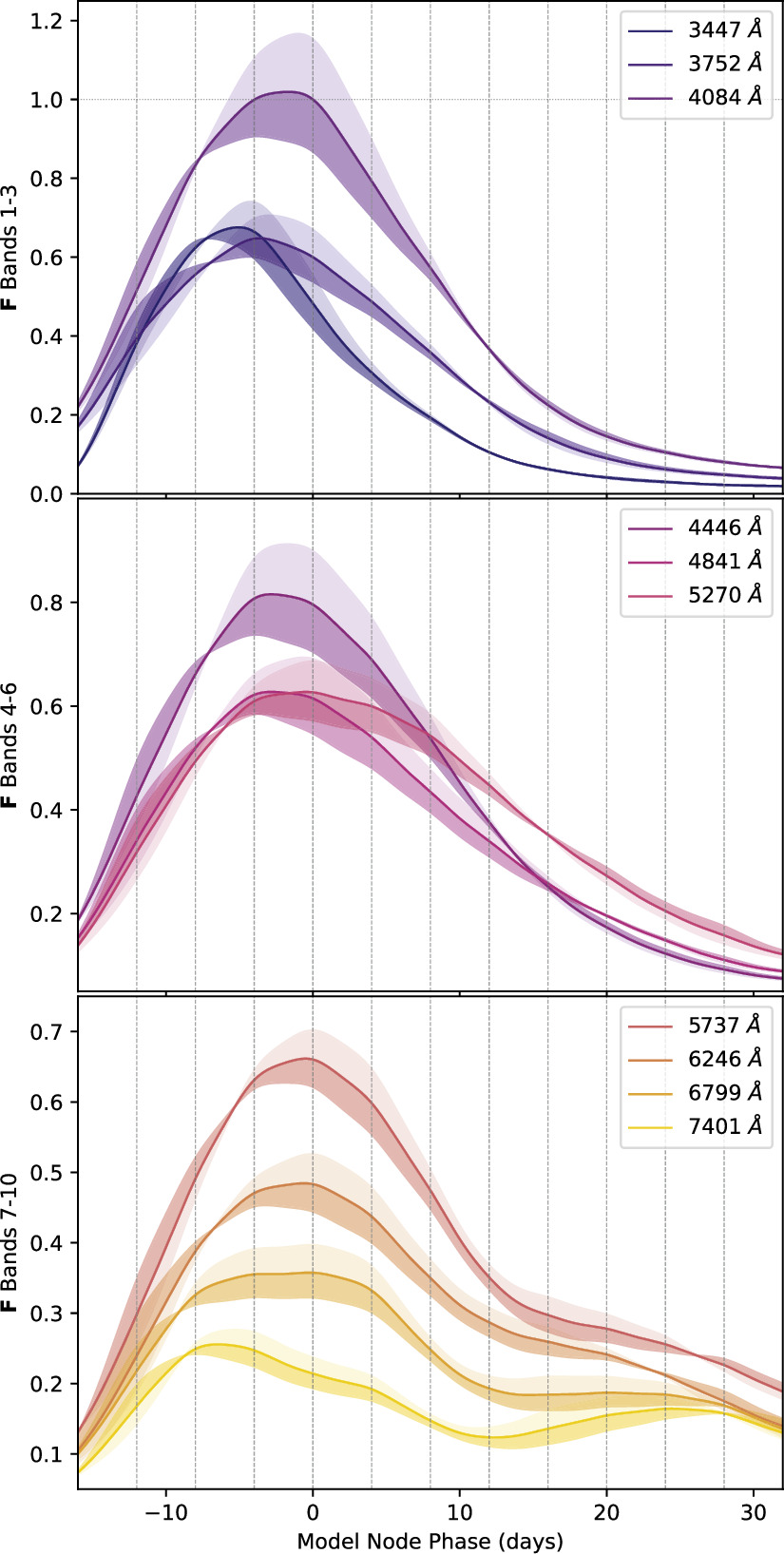

Figure 10 presents GPMP interpolations of each band's best-fit Fλ,0 nodes as solid curves. The fixed band 3 template is the third solid curve presented in the top plot of Figure 10. The ubiquitous NIR bump is recovered for redder bands (bottom plot of Figure 10), with this second maximum occurring ≈25 days after our fixed-band peak brightness as expected (S. W. Jha et al. 2019). Apart from the reddest template curve centered at 7401 Å, the peak brightness phase per band occurs earlier for bluer bands and later for redder bands, again consistent with established trends (S. W. Jha et al. 2019). As would be expected by its I-band overlap, the reddest template curve exhibits somewhat more complex behavior than the other curves, such as the inflection point between its two local maxima (bottom plot, Figure 10).

Figure 10. A visualization of ±0.09 mag variation in s1 on the model's fiducial flux template F0, as warped by the phase-dependent chromatic flux template M1. Positive s1 contribution is given by light shaded regions, while negative s1 contribution is given by the dark shaded regions. Solid lines are the GPMP-interpolated light curve for that band's fiducial template nodes, which is deterministic (not stochastic) in our model. The top two plots illustrate recovered stretch-like behavior by the template M1, with broadening to narrowing of the effective light curve as s1 increases in value. The bottom plot captures stretch-like behavior further convolved with NIR bump variational modes (bump location and size). Note that these figures are not portraying model uncertainty, only model response to s1 parameter variation.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageNote that each fiducial template light curve's peak brightness phase does not align with our tp,i = 0 flux node, meaning t0 should not be interpreted as the fixed band 3's peak brightness phase. This is ultimately inconsequential, requiring only that each light curve's peak brightness phase be calculated deterministically after fitting, and has no effect on this analysis or its conclusions.

4.3. Phase-dependent Chromatic Flux Variation Template

As shown in Figure 10, the best-fit phase-dependent variation template M1 exhibits stretch-like behavior across all bands. The shaded regions in these plots show phase-dependent light-curve variation from −0.09 < s1 < 0.09 mag, which approximately captures the dispersion of the fit s1 parameter set (the set's standard deviation is 0.09 mag). The lighter shaded regions correspond to positive s1 values, while the darker correspond to negative values. As s1 increases (decreases), the Feff node values increases (decreases) with respect to F0's node values, resulting in each GPMP interpolation curve's global maximum decreasing (increasing). This change in Feff node scaling is offset for by a change in χ0, correlating the χ0 and s1 parameter sets (see Section 4.4).

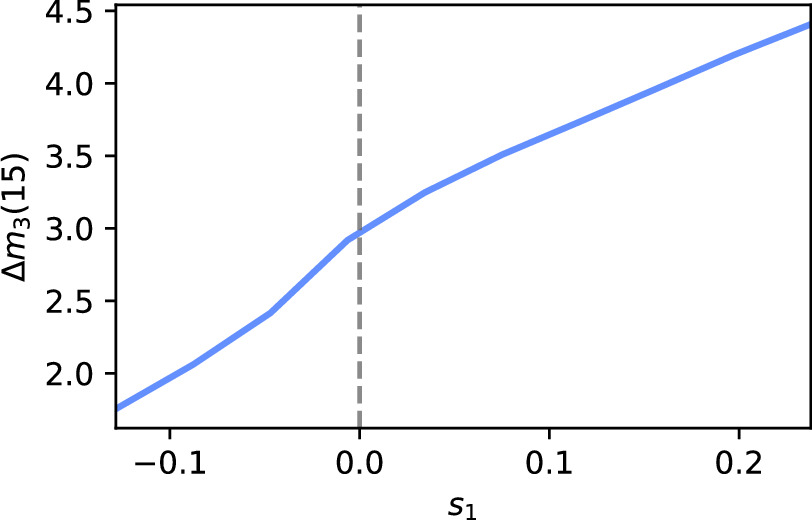

The sign of M1 template's contribution is a function of phase: for each curve there are two phases where the M1 template's contribution reverses in sign. For positive (negative) s1, the result is a narrowing (broadening) of the effective flux curve. The phase and degree of this broadening varies between bands in a manner consistent with D. Kasen & S. E. Woosley (2007), being more extreme for bluer wavelengths. Furthermore, Figure 11 plots our model's Δm3(15) as a function of s1, demonstrating our M1 template indeed recovers stretch-like behavior for this model's B-band analog fixed band 3.

Figure 11. The model's Δm3(15) (the ΔmB(15) analog for the fixed band 3) as a function of s1 calculated for the fixed band 3 along the training sample's obtained s1 value range.

Download figure:

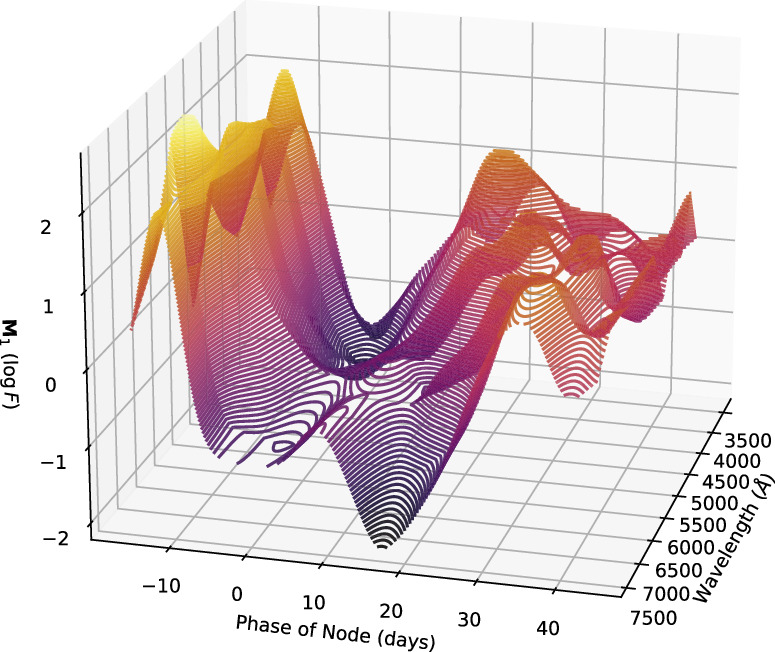

Standard image High-resolution imageFor redder bands, stretch-like behavior is convolved with NIR bump variation (bottom plot of Figure 10). A 3D mesh plot (Figure 12) best illustrates these two modes of NIR variation: bump depth and bump location. As expected, these variation modes also correlate with stretch (C. R. Burns et al. 2011; S. Dhawan et al. 2015), with stretch appearing as the valley-like feature in Figure 12.

Figure 12. A contoured 3D view of our phase-dependent variation template—this is our model's equivalent to SALT2's M1 stretch template. The valley-like structure corresponds to stretch-like behavior extracted by our M1 template.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageFor fixed band 3, the phase of maximum brightness relative to our zero-phase node is a function of s1. This movement in maximum brightness location, made clear in Figure 10, ranges from +1 day for our most negative s1 = −0.15 mag SN Ia to −3 days for our most positive s1 = 0.22 mag. Again, this has no effect on our analysis, requiring only an a posteriori calculation at the phase of maximum brightness if desired.

4.4. Per-supernova Results

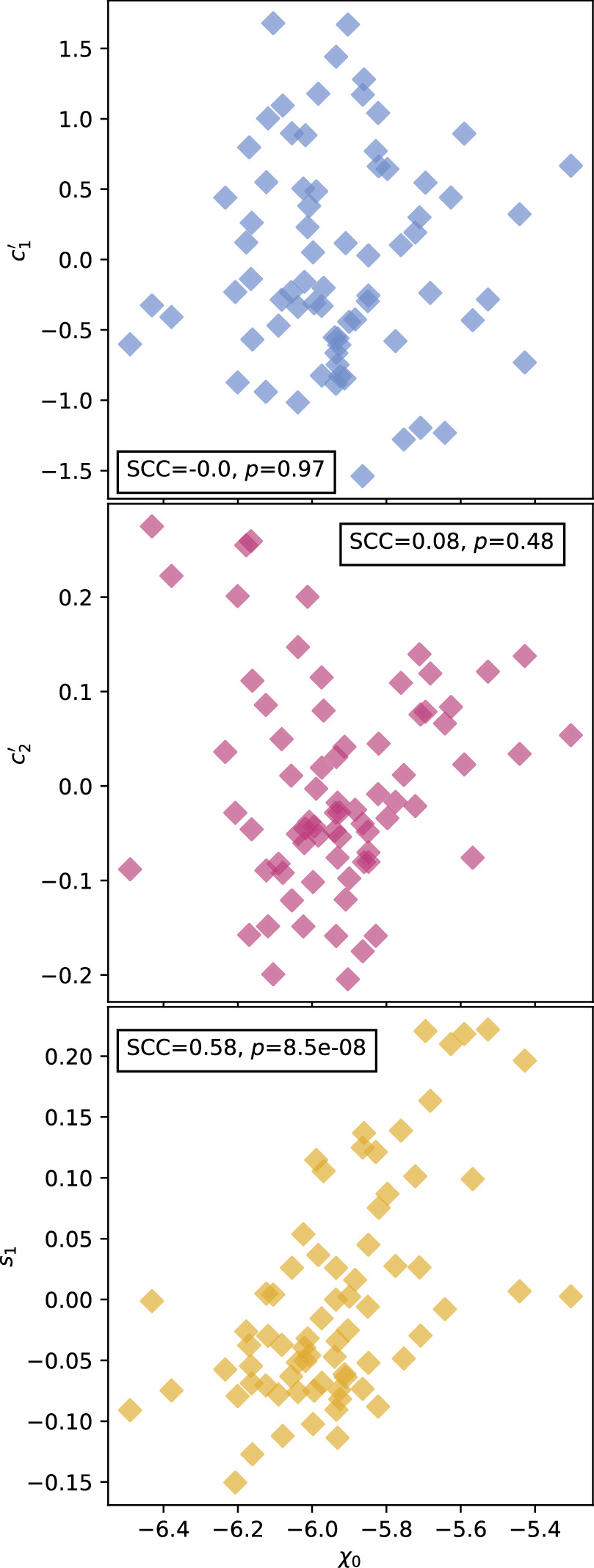

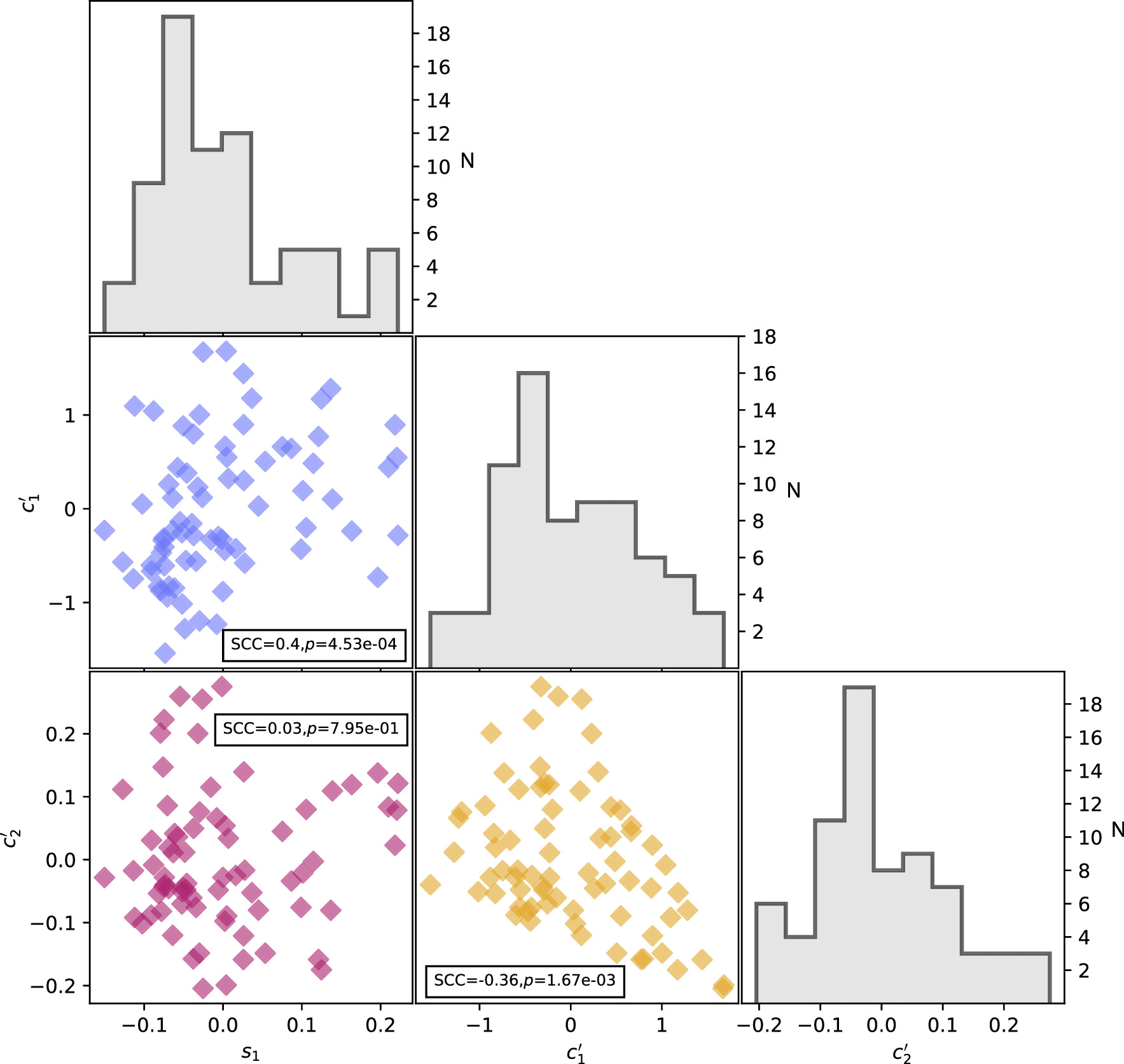

Each SN Ia is refit with template parameters fixed to the previously discussed best-fit solution. Scatterplots comparing parameter sets include Spearman rank correlation coefficient (SCC) calculations alongside corresponding p-values. For color, only the CCM89-derived basis parameter sets  and

and  are presented. As the MVR and CCM89-derived bases yield parallel

are presented. As the MVR and CCM89-derived bases yield parallel  planes, we choose to present results from the latter since the CCM89-derived basis is more readily interpreted—its first component is, by definition, a mathematically valid CCM89 curve. Note that we do not compare per-SN parameter sets from different basis decompositions.

planes, we choose to present results from the latter since the CCM89-derived basis is more readily interpreted—its first component is, by definition, a mathematically valid CCM89 curve. Note that we do not compare per-SN parameter sets from different basis decompositions.

In Figure 13, per-SN parameter sets for  ,

,  , and s1 are compared with their corresponding χ0 values. The measured SCC value of 0.59 between the training sample's s1 and χ0 parameter sets results from a varying s1 changing the resulting Feff scaling, requiring a compensating change in χ0 to offset (see Section 4.3). By construction, the

, and s1 are compared with their corresponding χ0 values. The measured SCC value of 0.59 between the training sample's s1 and χ0 parameter sets results from a varying s1 changing the resulting Feff scaling, requiring a compensating change in χ0 to offset (see Section 4.3). By construction, the  and

and  sets are de-correlated with χ0 (see Section 3.3). Higher rank correlations are recovered for

sets are de-correlated with χ0 (see Section 3.3). Higher rank correlations are recovered for  versus s1 and

versus s1 and  versus

versus  compared to

compared to  versus s1, as seen in the scatterplots of Figure 14.

versus s1, as seen in the scatterplots of Figure 14.

Figure 13. Comparison of fit  (top, blue),

(top, blue),  (middle, magenta), and s1 (bottom, yellow) samples against our χ0 samples. The correlation between χ0 and s1 arises from s1's changing of Feff's scale, which is then compensated for by a change in χ0. There are no correlations between either

(middle, magenta), and s1 (bottom, yellow) samples against our χ0 samples. The correlation between χ0 and s1 arises from s1's changing of Feff's scale, which is then compensated for by a change in χ0. There are no correlations between either  and χ0 or

and χ0 or  and χ0 by construction.

and χ0 by construction.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageFigure 14. Corner plot for the per-SN parameters s1,  , and

, and  . Magenta points compare s1 and

. Magenta points compare s1 and  , yellow points compare

, yellow points compare  and

and  , and blue points compare

, and blue points compare  and

and  parameter sets. We measure only marginal rank correlations between both

parameter sets. We measure only marginal rank correlations between both  vs. s1 and

vs. s1 and  vs.

vs.  . N is the number of SNe Ia.

. N is the number of SNe Ia.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageWe also quantify the fractional variance of the  and

and  bivariate distributions not explained by CCM89-like behavior. Each SN Ia phase-independent chromatic flux variation vector

bivariate distributions not explained by CCM89-like behavior. Each SN Ia phase-independent chromatic flux variation vector  is first normalized. The perpendicular component with respect to the CCM89 plane spanned by

is first normalized. The perpendicular component with respect to the CCM89 plane spanned by  of each normalized c is then calculated via a projection operation (see Appendix C.2). This resulting distribution has a median value of 0.13 with 68th percentiles [0.05, 0.4] and provides a measure of our sample's fractional variance attributable to captured phase-independent chromatic variability which is not dust-like. Unsurprisingly, dust-like variation, which explains the remaining ≈87% variance, dominates the captured phase-independent variability. Even if this dust-like variation was the exclusive result of actual dust extinction (no “leaking” of intrinsic variability into dust-like behavior), the remaining ≈13% variance, which instead arises from intrinsic variability in the sample, is not negligible.

of each normalized c is then calculated via a projection operation (see Appendix C.2). This resulting distribution has a median value of 0.13 with 68th percentiles [0.05, 0.4] and provides a measure of our sample's fractional variance attributable to captured phase-independent chromatic variability which is not dust-like. Unsurprisingly, dust-like variation, which explains the remaining ≈87% variance, dominates the captured phase-independent variability. Even if this dust-like variation was the exclusive result of actual dust extinction (no “leaking” of intrinsic variability into dust-like behavior), the remaining ≈13% variance, which instead arises from intrinsic variability in the sample, is not negligible.  , with

, with  in particular, is capturing a discernible addition of SN Ia variation over past two-component models (i.e., SALT2).

in particular, is capturing a discernible addition of SN Ia variation over past two-component models (i.e., SALT2).

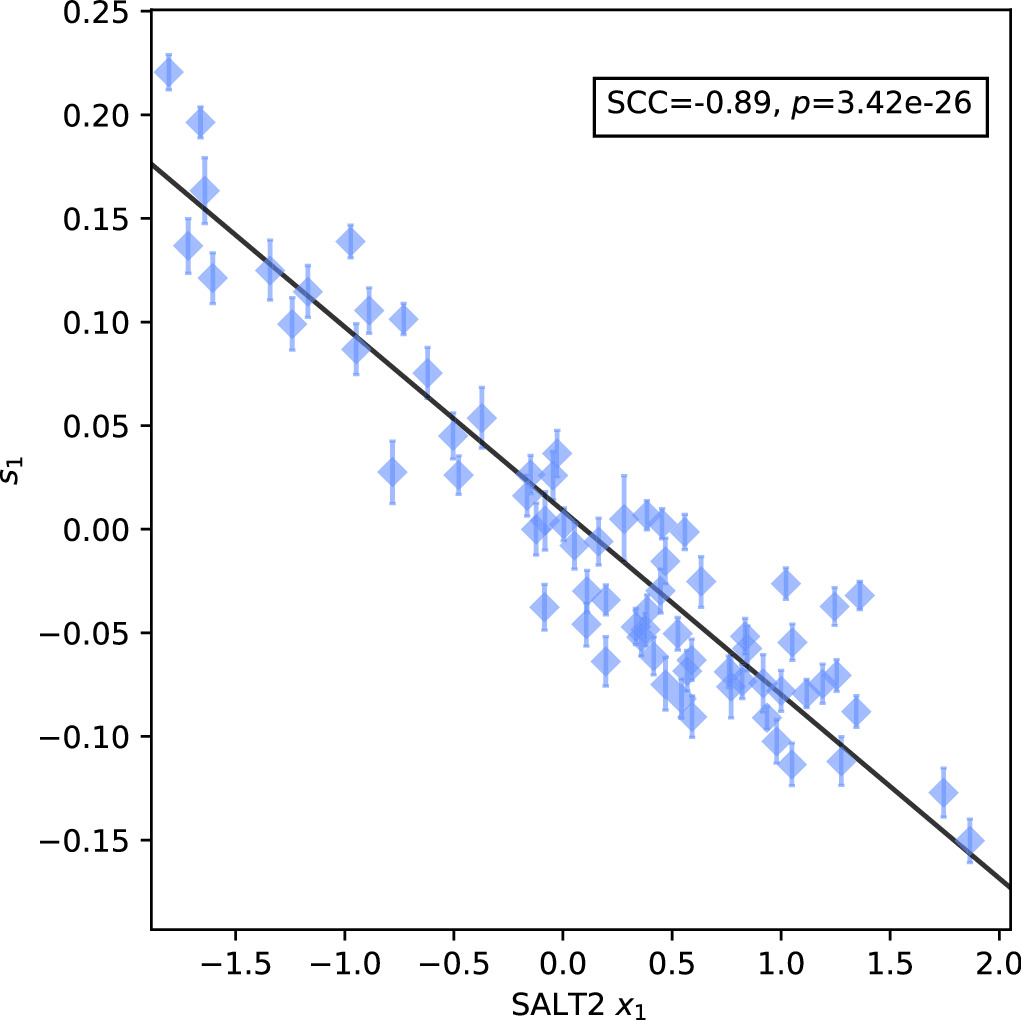

4.4.1. Comparison to SALT2

This new SN Ia model and SALT2 are trained using optical wavelength observations, with neither making assumptions about dust extinction, making SALT2 an obvious comparator. One technical difference is our model's accounting for phase-dependent variability with a multiplicative variation template as opposed to SALT2's flux variation linear component, which is obviously additive in flux space. Nonetheless, s1 and x1 should correlate. This is the case as seen in Figure 15, with a rank correlation of −0.89 between x1 and s1. As presented in Section 4.3, this model's M1 templates obtains stretch-like behavior, just as SALT2's first-order variation template M1(t, λ) does.

Figure 15. Per-SN comparison of our stretch parameter s1 vs. SALT2's stretch proxy x1. An ordinary least squares linear best fit is provided with a solid black line. Error bars correspond to 68th percentiles.

Download figure:

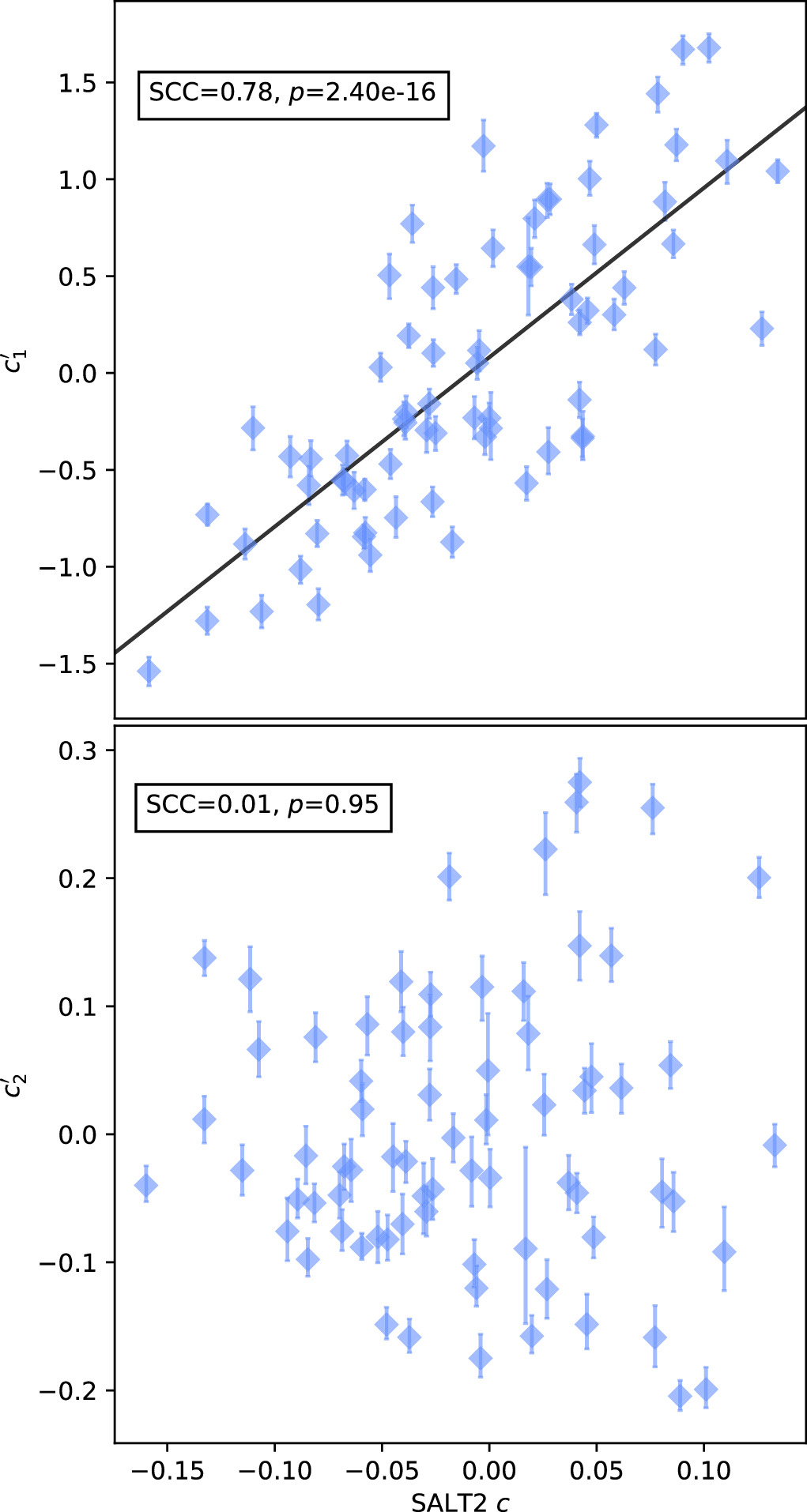

Standard image High-resolution imageThe phase-independent chromatic flux variation template basis  is selected without consideration of SALT2's CL(λ) phase-independent chromatic variation model. As such, any correlations between

is selected without consideration of SALT2's CL(λ) phase-independent chromatic variation model. As such, any correlations between  or

or  and SALT2 c are nontrivial—as seen in the top plot of Figure 16, only SALT2 c and

and SALT2 c are nontrivial—as seen in the top plot of Figure 16, only SALT2 c and  are correlated with a rank correlation of 0.78. Considering

are correlated with a rank correlation of 0.78. Considering  is the maximal CCM89 dust-like vector allowed, that SALT2 c and

is the maximal CCM89 dust-like vector allowed, that SALT2 c and  are strongly correlated is because SALT2's CL(λ) template predominately captures dust-like variation. Indeed, the latest SALT3 recovers a CL(λ) curve that is consistent with SALT2 and similarly aligns with CCM89 between 4000 and 7000 Å (W. D. Kenworthy et al. 2021). As seen in Figure 13 of W. D. Kenworthy et al. (2021), both of the SALT2 and SALT3 CL(λ) templates begin to diverge from CCM89 near where

are strongly correlated is because SALT2's CL(λ) template predominately captures dust-like variation. Indeed, the latest SALT3 recovers a CL(λ) curve that is consistent with SALT2 and similarly aligns with CCM89 between 4000 and 7000 Å (W. D. Kenworthy et al. 2021). As seen in Figure 13 of W. D. Kenworthy et al. (2021), both of the SALT2 and SALT3 CL(λ) templates begin to diverge from CCM89 near where  starts to exhibit most of its variability.

starts to exhibit most of its variability.

Figure 16. A per-SN comparison of our per-SN chromatic flux variation parameters  (top) and

(top) and  (bottom) against SALT2's c parameter. We measure a clear rank anticorrelation between

(bottom) against SALT2's c parameter. We measure a clear rank anticorrelation between  and SALT2 c, but measure no correlation between

and SALT2 c, but measure no correlation between  and SALT2 c. We interpret this as template

and SALT2 c. We interpret this as template  capturing chromatic flux variation not modeled by SALT2. An ordinary least squares linear best fit between

capturing chromatic flux variation not modeled by SALT2. An ordinary least squares linear best fit between  and SALT2 c is provided by a solid black line. Error bars correspond to 68th percentiles.

and SALT2 c is provided by a solid black line. Error bars correspond to 68th percentiles.

Download figure: