Abstract

The source of the Galactic lithium (Li) has long been a puzzle. With the discovery of Li in novae, extensive research has been conducted. However, there still exists a significant disparity between the observed abundance of Li in novae and the existing theoretical predictions. Using the Modules for Experiments in Stellar Astrophysics, we simulate the evolution of novae with element diffusion and appropriately increase the amount of 3He in the mixtures. Element diffusion enhances the transport efficiency between the nuclear reaction zone and the convective region on the surface of the white dwarf (WD) during nova eruptions, which results in more 7Be being transmitted to the WD surface and ultimately ejected. Compared to the previous predictions, the abundance of 7Be in novae simulated in our model significantly increases. The result is able to explain almost all observed novae. Using the method of population synthesis, we calculate Li yield in the Galaxy. We find that the Galactic occurrence rate of novae is about 130 yr−1, and about 110 M⊙ Li produced by nova eruption is ejected into the interstellar medium (ISM). About 73% of Li in the Galactic ISM originates from novae and approximately 15%–20% of the entire Galaxy. This means that novae are the important source of Li in the Galaxy.

Original content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 licence. Any further distribution of this work must maintain attribution to the author(s) and the title of the work, journal citation and DOI.

1. Introduction

Lithium (Li) is an extremely fragile element that is destroyed in the hydrogen (H) capture reaction at temperatures as low as 2 × 106 K. Its dominant isotope, 7Li, is the decay product of 7Be with a half-life of 53.3 days. In the process of H burning, 7Be rapidly decays to 7Li through electron capture (pp II) after being formed via the proton–proton (pp) chain. 7Li itself is also destroyed through proton capture, resulting in very little Li surviving in the H burning process. This makes it almost impossible to accurately calculate the abundance of Li in most stars during their formation. The production of primordial 7Li is a sensitive function of the baryon-to-photon ratio and can be estimated within the framework of standard primordial nucleosynthesis as long as the baryon density is obtained from the initial deuterium abundance or fluctuations of the cosmic microwave background (Spergel et al. 2003; Bennett et al. 2013; Planck Collaboration et al. 2020). The expected primordial value is A(Li) ≈ 2.72 dex (Życzkowski et al. 1998; Coc et al. 2014), which is 3–4 times higher than the measured values in halo dwarf stars (Spite & Spite 1982; Planck Collaboration et al. 2020). This difference is often referred to as the cosmological Li problem (Fields et al. 2014).

Since the measured Li abundance in meteorites that preserves the protosolar in the interstellar medium (ISM) is A(Li) ≈ 3.3 dex (Asplund et al. 2009; Lodders et al. 2009), there is need for a galactic source to explain the increase from the initial value of 2.72 dex. This identification of the source is commonly known as the Galactic Li problem. The ISM is the material that fills the space between the stars within a galaxy. It consists primarily of gas (atomic, molecular, and ionized) and dust. Planetary nebulae, supernova explosions, and novae explosions all inject a large amount of chemical elements into the ISM. The ISM is crucial for the formation and evolution of stars, and it plays a key role in the chemical enrichment and energy balance of galaxies (Draine 2011). Various nucleosynthesis processes and sources have been proposed so far. One confirmed source of Li is spallation and fusion processes of galactic cosmic rays in the ISM. The integrated spallation process is estimated to contribute about 10% ∼ 20% to the measured 7Li in the entire Galactic lifetime (Prantzos et al. 1993; Romano et al. 2001; Prantzos 2012). Other proposed sources include spallation processes in the flares of low-mass active stars, red giants (RGs), asymptotic giant branch (AGB) stars, and neutrino-induced nucleosynthesis during a type II supernova (Starrfield et al. 1978; Spite & Spite 1982; Smith & Lambert 1989, 1990; Hernanz et al. 1996; Romano et al. 1999; Travaglio et al. 2001; Alibés et al. 2002; Prantzos 2012; Banerjee et al. 2016; Pignatari et al. 2016; Tajitsu et al. 2016; Rukeya et al. 2017). Although Li abundance is indeed enhanced in some studies, their contribution to the entire Galaxy is too small. Therefore, other sources are still needed for the Galaxy to reach its current value. Subsequently, Romano et al. (2001) and Prantzos et al. (2017) found that low-mass giants are the best candidates for reproducing the late rise of the Li metallicity plateau. However, high A(Li) cannot be sustained for a long period due to convective activity in these stars, and the low percentage of Li-rich giants also indicates this (Casey et al. 2016; Yan et al. 2018; Gao et al. 2022). Therefore, their contribution to the enrichment of Li in the Galactic ISM remains quite uncertain.

For many years, classical novae have been proposed as feasible sites for Li production (Arnould & Norgaard 1975; Starrfield et al. 1978). The novae eruption is the result of unstable hydrogen-burning on the CO or ONeMg white dwarf (WD) surfaces, which accrete hydrogen-rich material from their main-sequence (MS) or RG phase companions in low-mass, close binary systems (Starrfield et al. 2009, 2016; Jose 2016; Rukeya et al. 2017). When the companion star fills its Roche Lobe, the hydrogen-rich material flows through the inner Lagrange point to the WD and accretes onto its surface. This material accumulates and is compressed until thermonuclear runaway (TNR) is triggered, resulting in mass ejection that ultimately pollutes the interstellar environment. Both theoretical and observational evidence confirm that novae contribute many nucleosynthetic isotopes to the Galactic ISM (José & Hernanz 1998; Starrfield et al. 1998), for example, the elements 7Li and 7Be.

7Be is generated through the 3He(α, γ)7Be reaction at a temperature of 150 million K (Hernanz et al. 1996). To avoid destruction, 7Be needs to be transported to cooler regions quickly through convection, as described in the Cameron–Fowler (CF) mechanism (Cameron & Fowler 1971). When these cooler regions are subsequently ejected, the absorption lines of 7Be during nova outbursts can be observed (José & Hernanz 1998), eventually decaying into 7Li. This view was later confirmed by observations by Izzo et al. (2015) who detected a potentially detectable 7Li i λ6708 absorption line in the spectrum of the Nova Centauri 2013 (V1369 Cen), providing observational evidence for the presence of Li in nova explosions that had been predicted since the mid-1970s but only recently discovered. Subsequently, the observation studies continuously detected the progenitor nucleus 7Be or 7Li in the prominent postoutburst spectra of classical novae (Tajitsu et al. 2015, 2016; Molaro et al. 2016, 2020, 2022, 2023; Izzo et al. 2018; Selvelli et al. 2018).

For a long time, people have continuously used theoretical models to calculate the accurate Li yield from nova explosions. Hernanz et al. (1996) and José & Hernanz (1998) calculated the theoretical values for different WD masses and mixing ratios of ejected material in their nova models. Then Rukeya et al. (2017) expanded on the nova grid model and computed more detailed mass and Li yields of the ejecta. They concluded that the Li produced in novae accounts for 10% of the total Galactic ISM (∼ 150 M⊙) production. However, Starrfield et al. (2024) predicted that the abundance of Li ejected from CO novae explosions is A(Li) ≈ 6, but most observed novae showed A(Li) > 7 (i.e., A(Li) = Log(N(7Li)/N(H)+12)). The actual abundance of ejected Li is 1 order of magnitude higher than the theoretical predictions (Izzo et al. 2015, 2018; Molaro et al. 2016, 2022; Arai et al. 2021).

This suggests that traditional nova models may have deficiencies in their physical mechanisms, and the Galactic Li problem unresolved. Subsequently, researchers have attempted different calculation methods by adjusting the mass distribution of binary systems, eruption time intervals, criteria for eruptive episodes, metallicity, and accretion material mixing ratios to compute Li yields under different scenarios (José & Hernanz 1998; Starrfield et al. 2009, 2020; Cescutti & Molaro 2019; José et al. 2020). Kemp et al. (2022b) demonstrated that by using the yield values given in Molaro et al. (2023) novae can definitely be the main factories of Li in the Galaxy, while by using the theoretical values they could not. Therefore, finding a reasonable nova model and Li production mechanism that aligns with the observations and theoretical values is of great significance in addressing the Galactic Li problem and even the cosmological Li problem. It is well known that the chemical composition of the ejecta in nova explosions depends on the surface chemical element composition of the WDs at the moment of the eruption. Several factors can influence the chemical composition of the WD’s surface, such as metallicity, accretion efficiency, and element diffusion (Kippenhahn et al. 1980; Dupuis et al. 1992; Zhu et al. 2021). The effects of nuclear reaction rate, accretion efficiency, and metallicity on the surface material of WDs have been explored by Starrfield et al. (2016, 2020) and Kemp et al. (2022a, 2022b). However, element diffusion has been rarely considered. Element diffusion is a dynamic process that alters the distribution of chemical elements within a star. It primarily results from the combined effects of pressure, temperature, and material concentration. Kovetz & Prialnik (1985) investigated effective diffusion between the accreted layer and the inner regions for accreting WD, and they found that diffusion can lead to enrichment of carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen (CNO) and other metals in the ejected envelope. However, CNO enhancements are possible in CO novae only in the absence of the He buffer (Iben et al. 1991). The presence of a helium layer would prevent the diffusion of CNO and metals (such as 3He), although the average abundance of helium is almost the same as that of solar (Gehrz et al. 1998; Yaron et al. 2005). Therefore, the 3He inside the WD cannot be effectively brought to the envelope where TNR occurs by element diffusion, and there are other sources of 3He in the envelope (Iben et al. 1991). In our model, 3He comes from the accreted material from the donor star but not the from the interior of the WD. The role of element diffusion in our model is that 7Be produced by 3He(α, γ)7Be among TNR can be taken more efficiently to then WD surface and then can be ejected more easily. Therefore, a large amount of 7Be can be detected in the ejecta of the nova, ultimately decaying into 7Li.

In this paper, we assume the novae as main sources of Li. In particular, Section 2 describes the details of the nova model. Section 3 presents the 7Li yields predicted by our models and the comparative analysis of the observation and theoretical results. The summary is given in Section 4.

2. Models

Our nova model has been using version 12778 of the Modules for Experiments in Stellar Astrophysics (MESA) stellar evolution code, which constructs CO and ONeMg nova models based on its WD and nova modules (Paxton et al. 2011, 2013, 2015, 2018, 2019). The advantage of MESA is its ability to calculate nova outbursts by dividing the outer shell mass of WD into approximately 1000 or more cells, resulting in smaller errors. At each cell, temperature, density, and isotopic composition are calculated. In MESA, when the luminosity of a star (L) exceeds the super-Eddington luminosity (LEdd), it will trigger mass loss. The mass loss rate is

where  and LEdd = (4π

GcM)/κ.

M and R are the mass and radius, respectively, while κ is the Rosseland mean opacity at the WD's surface. The scaling factor is taken as ηEdd = 1 (Denissenkov et al. 2013). The cells will be ejected when L > LEdd. In this paper, it is set that the nova ejection begins when the total WD luminosity (L) is greater than 104 times the solar luminosity (L⊙) and ends when less than 103

L⊙. Therefore, the MESA code can be used to simulate multicycle nova and construct a large-scale nova model grid from the accretion phase to expansion, explosion, and ejection phases (Paxton et al. 2011, 2013, 2015).

and LEdd = (4π

GcM)/κ.

M and R are the mass and radius, respectively, while κ is the Rosseland mean opacity at the WD's surface. The scaling factor is taken as ηEdd = 1 (Denissenkov et al. 2013). The cells will be ejected when L > LEdd. In this paper, it is set that the nova ejection begins when the total WD luminosity (L) is greater than 104 times the solar luminosity (L⊙) and ends when less than 103

L⊙. Therefore, the MESA code can be used to simulate multicycle nova and construct a large-scale nova model grid from the accretion phase to expansion, explosion, and ejection phases (Paxton et al. 2011, 2013, 2015).

For CO WD models, the nuclear network selects pp_and_cno_extras_net, while the ONeMg WD models uses h_burn_net. These nuclear networks include the CNO burning cycle and the proton–proton reaction chains (pp chain), the latter of which include 3He(α, γ)7Be, 7Be(e−, ν)7Li, 8B(γ, p)7Be, 7Li(p, α)4He, and 8B(e+, ν)8Be*(2α), which are sufficient nuclear synthesis to treat 7Be and 7Li nucleosynthesis (Starrfield et al. 1978). It is worth noting that the degree of mixing also affects the mass and isotopic abundance of the ejected material (Hernanz et al. 1996). José & Hernanz (1998), Denissenkov et al. (2014), and Rukeya et al. (2017) have used the NOVA and MESA codes to calculate the nova eruption model, assuming that the degree of mixing could be 25%–50%. That is, 25% of WD material and 75% of solar material or 50% of WD material and 50% of solar material (Lodders et al. 2009). We adopted the latter, which is more widely used. However, 7Be simulated by the previous models did not explain the observed values. Subsequent studies suggested that there is a corresponding relationship between 7Be and 3He (Boffin et al. 1993; Hernanz et al. 1996; Molaro et al. 2020; Denissenkov et al. 2021).

The importance of 3He for novae was first studied by Schatzman (1951) in the context of a theory of novae powered by thermonuclear detonations. The initial 3He abundance for the accreted matter could potentially come from the donor star (Shara 1980; Townsley & Bildsten 2004). As the donor star is ascending the RG branch, the convection dredges up 3He-enriched material to the surface, which is later expelled into the ISM by wind or is accreted by WDs in nova systems (Shen & Bildsten 2009; Denissenkov et al. 2021). Dantona & Mazzitelli (1982) and Iben & Tutukov (1984) found that the mass fraction of accreted X0(3He) can reach values as high as 4 × 10−3 during the evolution of systems with low-mass donors. Furthermore, some observational studies have shown the existence of relatively high levels of 3He/H in certain planetary nebulae (Rood et al. 1992; Balser & Bania 2018). If 3He abundance of the donor’s envelope is much higher than that in the Sun, this would almost align the model predictions of 7Be production with observations (Molaro et al. 2020). However, observations of the ISM indicate that the abundance of 3He in the Galaxy cannot be too high (Dearborn et al. 1996; Romano & Matteucci 2003). Denissenkov et al. (2021) demonstrated that an excess of 3He in accreted material would actually reduce the production of 7Be. Their work showed that when X0(3He) exceeds 3 × 104, it could lead to the early onset of the TNR, result in a reduction in peak temperature and accreted mass, and thereby suppress the production of 7Be. While this level of 3He-induced 7Be abundance increase would be slightly elevated, most of it would still be consumed at high temperatures and not transported to the WD surface to generate sufficient 7Li, thus not closing the gap with observations. Therefore, an effective transport mechanism is required to safely transport 7Be to the WD surface and allow it to survive. Element diffusion provides an effective pathway for this.

Elemental diffusion in the stellar interior is mainly driven by a combination of pressure gradients (or gravity), temperature gradients, compositional gradients, and radiation pressures. By solving the Burgers equation (Burgers 1969), Thoul et al. (1994) proposed a general method of arranging the entire system of equations into a single-matrix equation, so that the relative concentrations of various species have no approximate values and the number of elements considered is not limited. Therefore, this method is applicable to various astrophysical problems. In MESA, the method of Thoul et al. (1994) is used to calculate the diffusion of chemical elements within stars (Paxton et al. 2015, 2018). This diffusion effect can bring internal elements to the surface. We speculate that when WD accretes enough hydrogen-rich material from the companion star to reach the critical point, TNR occurs. The thermal instability caused by TNR leads to the appearance of a convective zone, which extends from approximately the middle of the combustion shell to the surrounding noncombustion helium layer (Cameron & Fowler 1971). The convective zone can bring 7Be from the stellar interior to the surface, which is the CF mechanism. Element diffusion improves the mixing efficiency of the entire convection zone, bringing more 7Be to the surface. When a nova explosion occurs, a large amount of 7Be on the surface is ejected and decays into 7Li in the ISM through a short half-life. This work utilizes MESA to construct a large-scale nova grid by setting different basic parameters and calculates the 7Li production of the nova.

MESA is a 1D code that only simulates spherically symmetric nova outbursts. However, based on the images of NOVA V5668 SAG combining the optical and radio observations from the Hubble Space Telescope and the Very Large Array telescope, Mukai & Sokoloski (2019) suggested that the geometry distribution of nova ejecta is not spherical symmetry but is the shape of an equatorial torus. It indicates that ejecta from novae have a very complicated structure. It is unclear which physical process lead to such an unsymmetric structure. Up until now, there have been few instances of 2D or 3D simulations depicting nova outbursts. Therefore, it should be noted that the MESA nova model also has its limitations.

3. Result

According to Yaron et al. (2005), the WD mass (MWD), accretion rate ( ), WD core temperature (Tc), and composition of the accreted material constitute the four basic input parameters that determine the nova eruption (Jose 2016; Starrfield et al. 2016). Yaron et al. (2005) constrained the parameters of the nova eruption and set a 3D restricted space for the nova eruption conditions. Our model set the Tc at 3 × 107 K and selected the CO WD model mass at 0.5 M⊙, 0.6 M⊙, 0.7 M⊙, 0.8 M⊙, 0.9 M⊙, 1.0 M⊙, 1.1 M⊙, and 1.2 M⊙ and the ONeMg WD model mass at 1.0 M⊙, 1.1 M⊙, 1.2 M⊙, and 1.3 M⊙ with accretion rates(

), WD core temperature (Tc), and composition of the accreted material constitute the four basic input parameters that determine the nova eruption (Jose 2016; Starrfield et al. 2016). Yaron et al. (2005) constrained the parameters of the nova eruption and set a 3D restricted space for the nova eruption conditions. Our model set the Tc at 3 × 107 K and selected the CO WD model mass at 0.5 M⊙, 0.6 M⊙, 0.7 M⊙, 0.8 M⊙, 0.9 M⊙, 1.0 M⊙, 1.1 M⊙, and 1.2 M⊙ and the ONeMg WD model mass at 1.0 M⊙, 1.1 M⊙, 1.2 M⊙, and 1.3 M⊙ with accretion rates( ) of 1 × 10−11

M⊙ yr−1, 1 × 10−10

M⊙ yr−1, 1 × 10−9

M⊙ yr−1, 1 × 10−8

M⊙ yr−1, and 1 × 10−7

M⊙ yr−1. In addition to the above four parameters, it is expected that material transferred from the companion (solar-like) will mix with the outer layers of the WD. This model adopts the widely accepted composition of 50% WD material and 50% solar material. Solar component data are taken from Lodders et al. (2009). Molaro et al. (2020) argued that the variety of high 7Be/H abundances in nova could be originated in a higher than solar content of 3He in the donor star. Observations show relatively high levels of 3He/H in some planetary nebulae, but observations of ISM indicate that the abundance of 3He in the Galaxy cannot be too high (Rood et al. 1992; Dearborn et al. 1996; Romano & Matteucci 2003; Balser & Bania 2018). According to the X0(3He) range of 2.96 × 10−5 ∼2.96 × 10−3 used by Denissenkov et al. (2021), we set X0(3He) to be 4 × 104.

) of 1 × 10−11

M⊙ yr−1, 1 × 10−10

M⊙ yr−1, 1 × 10−9

M⊙ yr−1, 1 × 10−8

M⊙ yr−1, and 1 × 10−7

M⊙ yr−1. In addition to the above four parameters, it is expected that material transferred from the companion (solar-like) will mix with the outer layers of the WD. This model adopts the widely accepted composition of 50% WD material and 50% solar material. Solar component data are taken from Lodders et al. (2009). Molaro et al. (2020) argued that the variety of high 7Be/H abundances in nova could be originated in a higher than solar content of 3He in the donor star. Observations show relatively high levels of 3He/H in some planetary nebulae, but observations of ISM indicate that the abundance of 3He in the Galaxy cannot be too high (Rood et al. 1992; Dearborn et al. 1996; Romano & Matteucci 2003; Balser & Bania 2018). According to the X0(3He) range of 2.96 × 10−5 ∼2.96 × 10−3 used by Denissenkov et al. (2021), we set X0(3He) to be 4 × 104.

3.1. Novae Models as Stellar Sources of Li

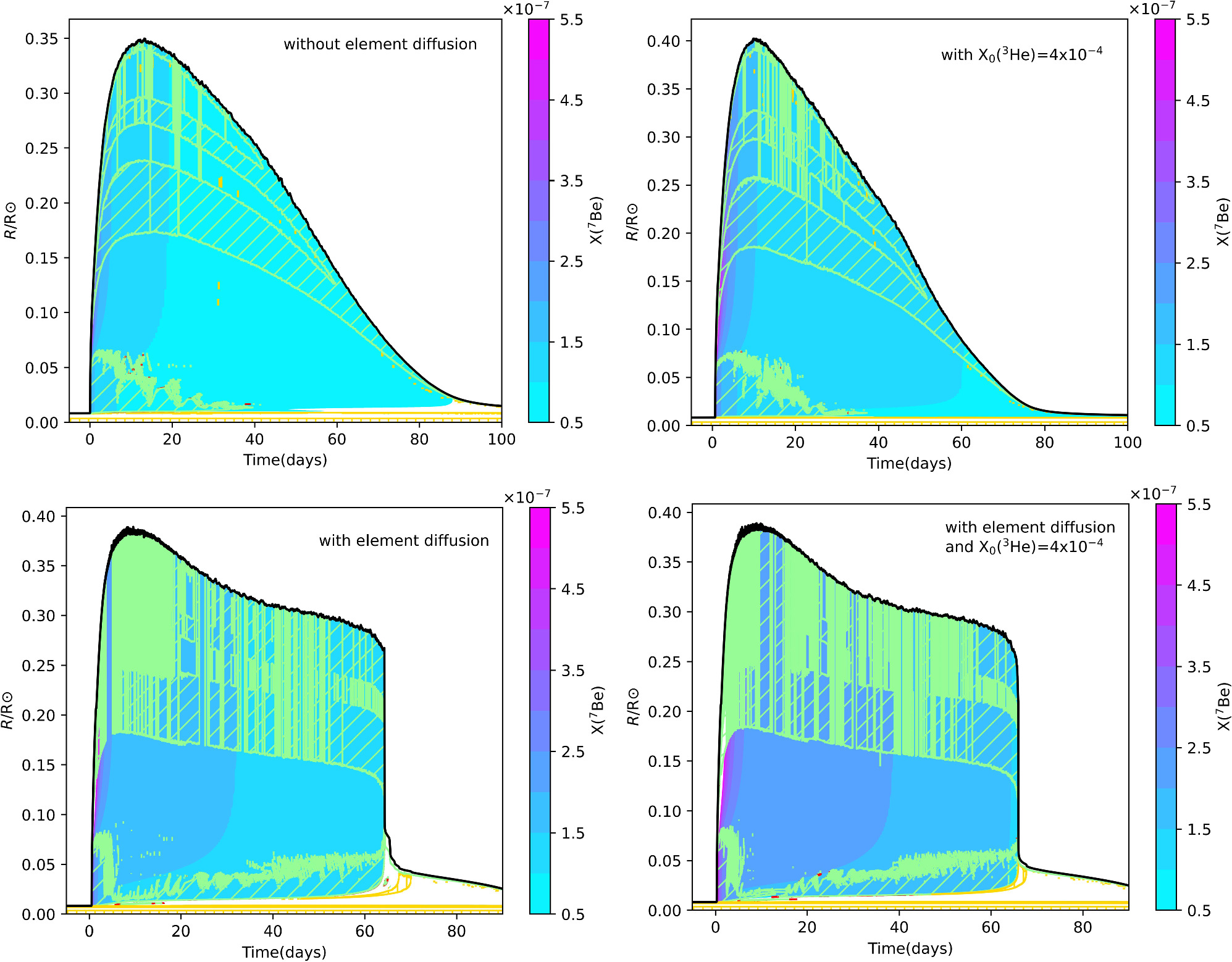

It is well known that during the occurrence of TNR, there are intense nuclear reactions, primarily dominated by hydrogen burning due to the WD accreting hydrogen-rich material from the companion. During hydrogen burning, a large amount of 7Be is produced through 3He(α, γ)7Be, with some being convectively transported to the WD's surface, while the rest is depleted at high temperatures. In our models with element diffusion, the transport efficiency within the WD is enhanced. Figure 1 shows the evolution of elements during the nova explosion. The two left panels clearly display the effect of element diffusion. There are some blank discontinuous areas on the surface convection zone (green shadow) of the model without element diffusion, indicating weak or even no mixing activity in these areas, as shown in the upper-left panel. In Figure 1, the mixing area within the convection zone of the WD model with element diffusion becomes more continuous and dense, and the mixing activity becomes stronger, as shown in the lower-left panel. In the nova model with element diffusion, a large amount of 7Be generated by nuclear reactions is effectively transported by this strong mixing effect to the low-temperature region of the surface, thereby avoiding depletion at high temperatures. On the contrary, the model without element diffusion cannot send out more 7Be, which is consumed by high temperature.

Figure 1. Nova explosion process with MWD = 1M⊙ and  = 1 × 10−10

M⊙ yr−1. Profiles of 7Be during the nova explosion show in panels. The y-axis represents the boundary radius of the WD during the explosion, and the x-axis represents the lifetime of the nova explosion. The green shadow shows the convective zone of different models.

= 1 × 10−10

M⊙ yr−1. Profiles of 7Be during the nova explosion show in panels. The y-axis represents the boundary radius of the WD during the explosion, and the x-axis represents the lifetime of the nova explosion. The green shadow shows the convective zone of different models.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageMeanwhile, the improvement of 3He can generate more 7Be to contribute to the transport to the surface as shown by the top-right panel in Figure 1. The 3He increase greatly enhances the yield of 7Be in the envelope, which is shown by pink color area. However, the increase of 3He causes the convective region to move inward, resulting in the failure to bring 7Be to a sufficiently low-temperature surface. This result is consistent with Denissenkov et al. (2021), who stated that excessively high 3He actually reduces the 7Be of the nova ejection. However, combining the element diffusion and the increase of 3He, the large amount of 7Be produced via enhancing 3He can be efficiently transferred to the WD surface, which is clearly shown by the lower-right panel.

We find that the abundance of 7Be in the model combining the element diffusion and the increase of 3He can be increased by about 4–10 times. It means that the 7Be abundance calculated in this work is consistent with the observational values (Izzo et al. 2015; Tajitsu et al. 2015; Molaro et al. 2020, 2023).

In order to compare our results with the observations, we selected 13 published observational samples of CO and ONeMg novae with relatively accurate measurements of parameters such as mass and Be abundance (9 CO novae and 4 ONeMg novae; e.g., Tajitsu et al. 2015, 2016; Molaro et al. 2016, 2020, 2022, 2023; Izzo et al. 2018; Selvelli et al. 2018; Arai et al. 2021). We calculated the 7Be abundance ejected in a single nova eruption using the criterion that the eruption begins when the total WD luminosity (L) is greater than 104 L⊙ and ends when it is below 103 L⊙.

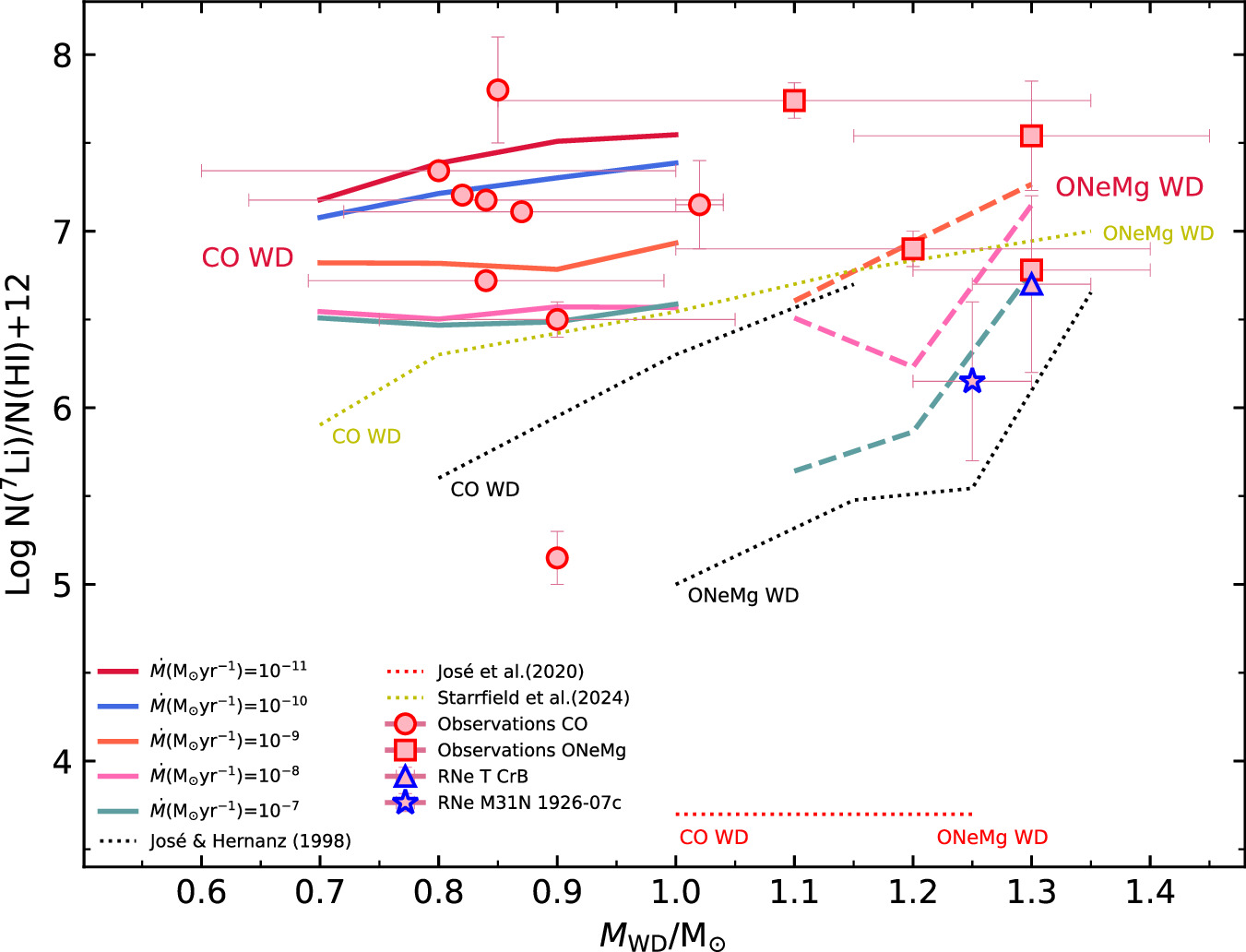

Figure 2 presents a comparison of the Be abundance produced by our simulated nova models with other models and matching to observations. The solid lines in different colors represent the CO nova models in the mass range of 0.7 M⊙–1.0 M⊙, with accretion rates from 1 × 10−7 M⊙ yr−1 to 1 × 10−11 M⊙ yr−1. The bold dashed lines depict the results of the ONeMg nova models in the mass range of 1.1 M⊙–1.3 M⊙, with accretion rates from 1 × 10−7 M⊙ yr−1 to 1 × 10−9 M⊙ yr−1. The results simulated by other literature also are given, such as the black and red dotted lines, representing models constructed by José & Hernanz (1998) and José et al. (2020) with 50% mixing and different WD masses, and the yellow dotted line representing models constructed by Starrfield et al. (2024) with 25% and 50% mixing and different WD masses. It is worth mentioning that our model provides 7Be yields for a range of accretion rates for each MWD rather than sampling only at a fixed accretion rate of 2 × 10−10 M⊙ yr−1 as in the other models mentioned above. It is evident that the 7Be abundance produced by our model is significantly higher compared to other models and covers almost all CO and ONeMg nova observational samples. In addition, we have made predictions for the two upcoming nova T CrB and M31N 1926-07 c eruptions in 2024 and marked the expected abundance of ejected 7Be in Figure 2. This result indicates that element diffusion enhances the transport efficiency between the interior and surface convective region of the WD, transporting sufficient 7Be to the surface region. Our results are consistent with observations and successfully explain the high 7Be abundance observed in the spectra after nova eruptions.

Figure 2. Comparison with observed Li abundances and the numerical simulations along with WD masses. Solid lines of different colors represent CO nova models with different accretion rates, while dashed lines represent ONeMg nova models. Red bordered circles denote the observed abundances of CO WD novae, and the squares denote the ONeMg WD novae. Since evaluating the quality of each WD is difficult, we simply plotted the error bars for each observed nova. The black, yellow, and red dotted lines correspond to theoretical predictions: highest values for each WD mass in José & Hernanz (1998), the “123–321 models” of José et al. (2020), and the 25%–50% mixing model of Starrfield et al. (2024), respectively. The blue pentagram represents the prediction of nova M31N 1926-07 c, and the blue triangle represents the nova T CrB.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageDue to the intense shock produced by the nova eruption, the ash of TNR is partially ejected into the ISM (Izzo et al. 2015; Tajitsu et al. 2015; Molaro et al. 2022, 2023; Starrfield et al. 2024). The ejected 7Be during the nova eruption decays into 7Li. This contributes to the total Li elements in the Galactic ISM. Therefore, we consider the abundance of ejected 7Be to be 7Li. In our simulations, Li mass produced by a nova outburst is calculated by  , where

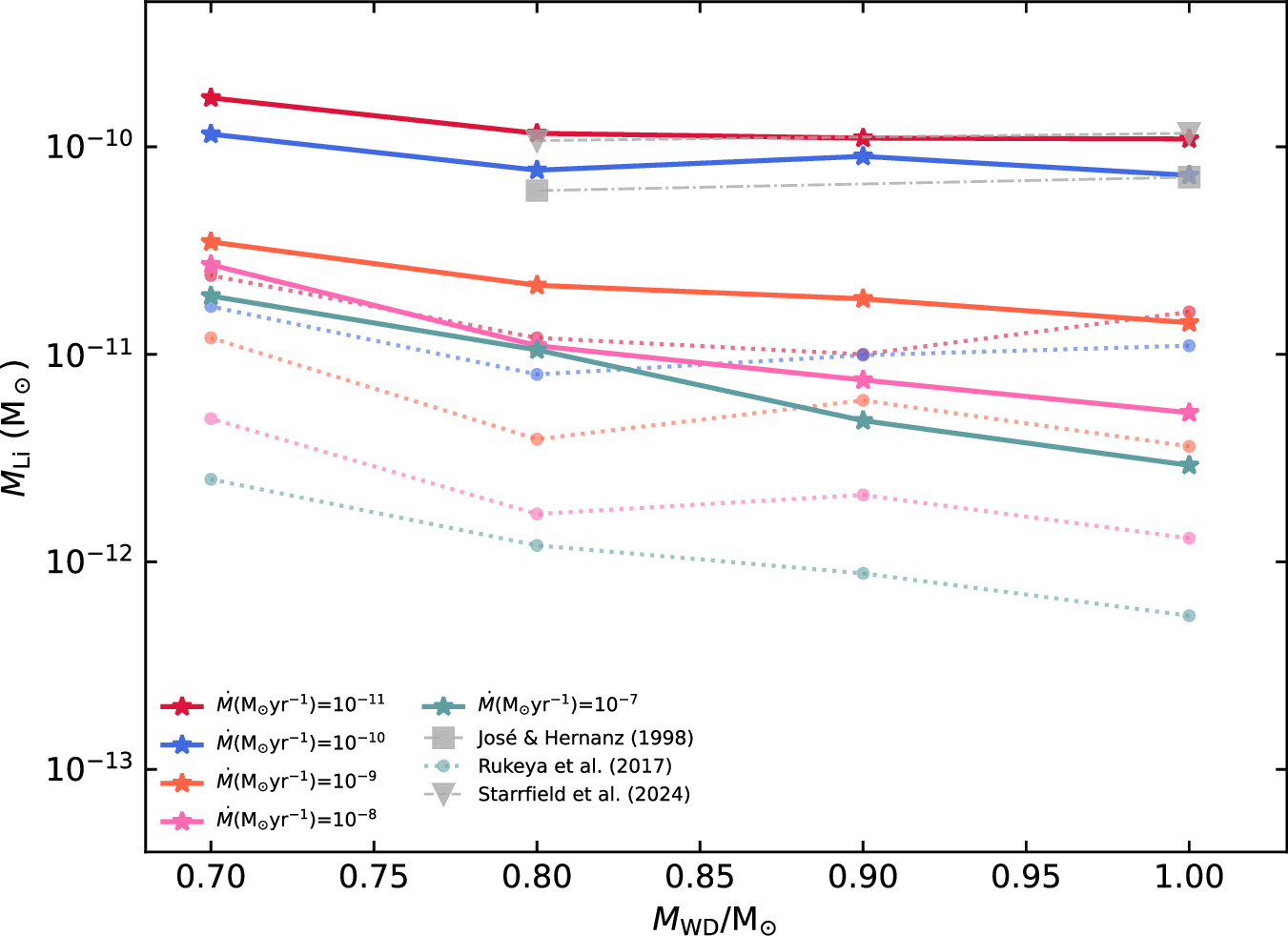

, where  is the mass-loss rate of the WD during the nova outburst (see Equation (1)) and X(7Li) is the mass fraction of 7Li in the nova ejecta. Figure 2 shows X(7Li). Compared to the previous theoretical results in José & Hernanz (1998), José et al. (2020), and Starrfield et al. (2024), the Li abundances in our simulations are higher and are closer to the observed values. Figure 3 gives the Li yields for a nova outburst. Our results are consistent with those of Starrfield et al. (2024). Based on Figures 2 and 3, our model may underestimate the mass-loss rate

is the mass-loss rate of the WD during the nova outburst (see Equation (1)) and X(7Li) is the mass fraction of 7Li in the nova ejecta. Figure 2 shows X(7Li). Compared to the previous theoretical results in José & Hernanz (1998), José et al. (2020), and Starrfield et al. (2024), the Li abundances in our simulations are higher and are closer to the observed values. Figure 3 gives the Li yields for a nova outburst. Our results are consistent with those of Starrfield et al. (2024). Based on Figures 2 and 3, our model may underestimate the mass-loss rate  , which is described by Equation (1). Observations indicate that the range of ejection masses falls between 10−6 and 10−4

M⊙, and José & Hernanz (1998) proposed an average ejection mass of 2 × 10−5

M⊙ for novae. In our models, we calculate the range of ejection masses falls between 9.17 × 10−7 and 5.93 × 10−5

M⊙. This result is slightly smaller than the observed value. As mentioned by Denissenkov et al. (2021), the increase of 3He in the accretion layer of our WD model can lead to an earlier TNR, a decrease in peak temperature and accreted mass, and ultimately result in a smaller ejection mass. By utilizing the Li and Be abundances and the ejected mass of WD output by MESA, we can obtain the Li mass for each burst ejection.

, which is described by Equation (1). Observations indicate that the range of ejection masses falls between 10−6 and 10−4

M⊙, and José & Hernanz (1998) proposed an average ejection mass of 2 × 10−5

M⊙ for novae. In our models, we calculate the range of ejection masses falls between 9.17 × 10−7 and 5.93 × 10−5

M⊙. This result is slightly smaller than the observed value. As mentioned by Denissenkov et al. (2021), the increase of 3He in the accretion layer of our WD model can lead to an earlier TNR, a decrease in peak temperature and accreted mass, and ultimately result in a smaller ejection mass. By utilizing the Li and Be abundances and the ejected mass of WD output by MESA, we can obtain the Li mass for each burst ejection.

Figure 3. 7Li yields vs. WD mass for all CO WDs in the grid.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageThe known novae are mainly concentrated in the range of the WD mass MWD = 0.8 M⊙–1.0 M⊙ and accretion rates around 1 × 10−10 M⊙ yr−1. In this range, our estimating Li yield reaches about 2 × 10−10 M⊙. This yield is slightly lower than the observations of the latest recurrent novae RS Oph (Izzo et al. 2015; Molaro et al. 2023), but it has already reached the same order of magnitude. It can be demonstrated that the nova model constructed in this paper can explain a large part of the observations in the Galaxy.

3.2. Contribution of 7Li Produced by Novae to the Galactic ISM

Theoretically, Rukeya et al. (2017) and Starrfield et al. (2024) estimated the specific contribution of 7Li produced by novae to the Galactic ISM, and they found that this contribution is approximately 10%. However novae as the main factories of Li in the Galaxy is something that was proposed in the 1970s by Arnould & Norgaard (1975) and Starrfield et al. (1978) and then demonstrated in Izzo et al. (2015), Tajitsu et al. (2015), and Molaro et al. (2016, 2023), based on the detection of Li and beryllium in a few novae. As shown by Figure 3, compared with the observations, the theoretical predictions underestimate Li yields produced by nova eruption.

In order to estimated the contribution of 7Li produced in our nova models to the Galactic ISM, we use the method of binary population synthesis (BPS), which has been applied by our group (Lü et al. 2006, 2009, 2013,

2020; Rukeya et al. 2017; Yu et al. 2019,

2021; Gao et al. 2022). BPS is a robust approach to evolve a large number of stars (including binaries) so that we can explain and predict the properties of a population of a type of stars (Han et al. 2020). In the population synthesis method for binary systems, input parameters include the star formation rate (SFR), the initial mass function (IMF) of the primaries, the initial mass ratio distribution, the initial orbital distribution, the eccentricity distribution, and the metallicity Z of binary systems. Here, with help of the rapid binary evolution (BSE) code, originating from Hurley et al. (2002), we can rapidly evolve large-sample binaries into nova binaries, in which MWD and the  are given.

are given.

Using MESA, we construct a grid for each nova eruption with MWD,  , and 7Li yields. For every nova simulated using the BSE code, by a bilinear interpolation of the above two physical quantities (MWD and

, and 7Li yields. For every nova simulated using the BSE code, by a bilinear interpolation of the above two physical quantities (MWD and  ) in MESA, one can then calculate the 7Li yields of every nova.

) in MESA, one can then calculate the 7Li yields of every nova.

Following Lü et al. (2006), in the method of population synthesis, we use the IMF of Miller & Scalo (1979) for the mass of the primary components and a flat distribution of mass ratios (Kraicheva et al. 1989; Goldberg & Mazeh 1994). A logarithmic flat distribution of initial separations between 10 and 106 R⊙ is used.

In the binary evolution, the common envelope (CE) evolution is critical important for the formation of nova systems. In BSE code, a combined parameter αCE × βCE is used to calculate CE evolution, where αCE is the fraction of binary binding energy, which is spent to expel the CE, and βCE is a parameter for the envelope structure of the donor. As discussed in Rukeya et al. (2017), αCE × βCE has a weak effect on 7Li yields produced by novae. In this work, we take αCE × βCE = 1.0. Simultaneously, circle orbits and solar metallicity for all binary systems are taken. To calculate the production rate of 7Li, we assume a constant SFR of 5 M⊙ yr−1 over the past 13 Gyr. In the case of a constant SFR, one simulates 106 binary systems, in which the primaries are more massive than 0.8 M⊙, which causes a statistical error for Monte Carlo simulations lower than 1% in classical novae.

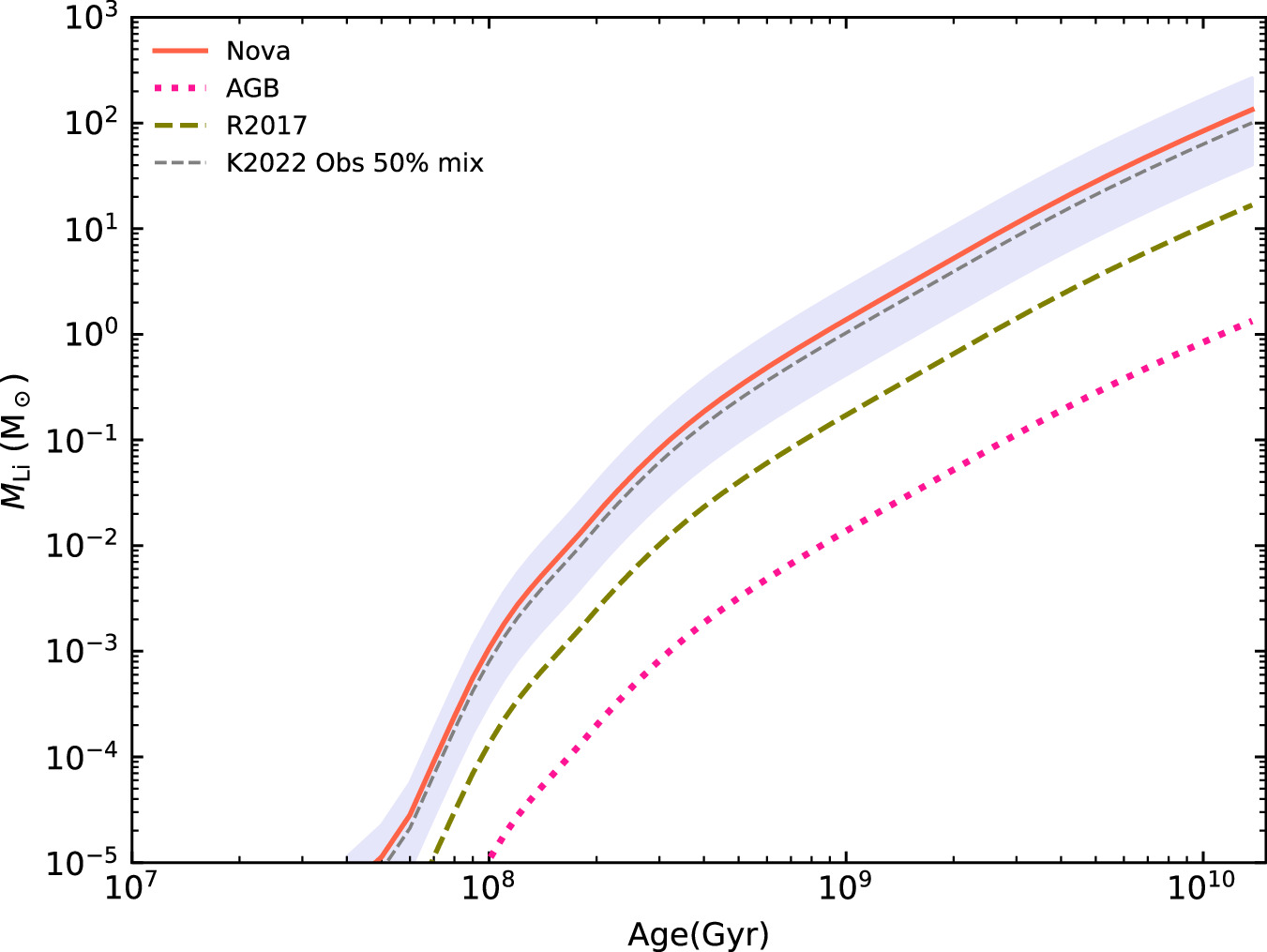

Figure 4 shows the evolutionary trajectory of 7Li produced by novae in the Galaxy at a constant SFR. According to the results of population synthesis, we obtained an average 7Li yield of about 6.4 × 10−11 M⊙ for each nova eruption, with approximately 8000 eruptions per nova binary, which is consistent with the previous results (Shara et al. 1986; Molaro et al. 2020). We then select nova systems from binary systems; the primary is a WD (including CO WD and ONeMg WD) and is accreting material from its secondary (an MS or RG star) via Roche lobe or stellar wind. The result is that among the 106 binary systems, 17,368 of them evolve into nova systems, accounting for approximately 1.7%. This is consistent with Rukeya et al. (2017; ∼1.5%) and Hurley et al. (2002; ∼1.9%). Based on this, we can conclude that the nova rate is 130 per year, which is within the predicted range (Sharov 1972; della Valle & Livio 1994; Shafter 1997, 2002, 2017). Among the 106 binary systems, 1.7% of them evolve into nova systems, resulting in an annual 7Li production of approximately 8.4 × 10−9 M⊙. Considering the age of the Galaxy to be 1.3 × 1010 yr, the contribution of novae to 7Li is estimated to be around 110 M⊙, compared to the total Li content of approximately 150 M⊙ in the ISM of the Galaxy (Hernanz et al. 1996; Molaro et al. 2016). Therefore, novae contribute approximately 73% of the 7Li in the Galactic ISM.

Figure 4. Li mass contributions from different sources as a function of Galactic age. The orange line represents our work, while the green and gray dashed lines represent the model results for Rukeya et al. (2017) and Kemp et al. (2022b). The shaded area is the error range of the latter. The results of AGB are represented by purple dotted lines.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageIn Figure 4, the solid red line represents the 7Li production at the age scale of the Galaxy, which is significantly higher than the results obtained by Rukeya et al. (2017). Kemp et al. (2022b) used the BPS code binary_c to simulate the novae in the Galactic ISM and, by using observed Li production, effectively explained the Li abundance in the early Sun. The 7Li production calculated in our model falls within the predicted error range for nova 7Li production, as demonstrated by Kemp et al. (2022b), proving that novae are indeed the most significant contributors to Li in the Galaxy. In addition, we also calculate the contribution of AGB stars using the same method. The hot bottom burning mechanism of AGB stars can bring Li elements to the surface, which will evolve into the planetary nebulae stage and are ultimately ejected into the ISM (Smith & Lambert 1990; Romano et al. 2001). After calculation, each AGB star produces approximately 10−9 M⊙ of 7Li, resulting in a final contribution to 7Li of around 1 M⊙, which is only 1%. This result is consistent with previous research (Romano et al. 2001; Doherty et al. 2014; Rukeya et al. 2017).

In our simulation, the Li mass produced by novae is ∼110 M⊙. This indicates that the novae can provide about 70% of the contribution to the Galactic ISM. However, compared to the total Li mass in the entire Galaxy (∼1000 M⊙; Molaro et al. 2023), Li produced by the novae is limited (about 15%–20%), and most Li may originate from the Big Bang.

4. Summary

We used the MESA code to construct nova models with element diffusion to calculate the abundance of 7Be on the surface of the WD during the occurrence of a TNR, as well as the production of 7Li after the eruption. Element diffusion enhances the efficiency of transport between the nuclear reaction zone and the convective region on the surface of the WD, allowing more material to be transported to the surface. Based on theoretical and observational evidence, we appropriately increased the amount of 3He produced during the mixing of material from the donor star and the accretor star, leading to more 7Be being produced. A transport channel within the WD is formed due to the increased transmission efficiency caused by element diffusion. This channel effectively transports the 7Be from the hydrogen-burning region of the WD to the convective envelope, where it decays into 7Li. Therefore, a large amount of 7Be produced by the nuclear reaction process in the WD can be transferred to the surface and ultimately ejected. The abundance of 7Be on the surface of the WD during the occurrence of a TNR in our model is consistent with the values obtained from the observed nova samples.

When the 7Be ejected by the nova eruption decays into 7Li in a short period of time, we use population synthesis methods to calculate the production of 7Li from the nova eruption. We find that about 1.7% of binary systems in the Galaxy can evolve into nova binaries. Every nova binary can evenly occur with about 8000 eruptions, and the occurrence of a nova eruption is about 130 yr−1. Each eruption can produce about 6.4 × 10−11 M⊙ of 7Li. There is about 110 M⊙ of Li produced by novae, which is about 73% of the total Li mass in the ISM of the Galaxy and approximately 15%–20% of the entire Galaxy. It means that novae are the primary source of Li in the Galactic ISM and also one of the important sources of Li in the entire Galaxy.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the anonymous referee for careful reading of the paper and constructive criticism. This work received the generous support of the National Natural Science Foundation of China under grants Nos. 12163005, U2031204, 12373038, and 12288102, the science research grants from the China Manned Space Project with No. CMSCSST-2021-A10, and the Natural Science Foundation of Xinjiang Nos. 2022D01D85 and 2022TSYCLJ0006.