Abstract

Metal-poor nearby galaxies hosting massive stars have a fundamental role to play in our understanding of both high-redshift galaxies and low-metallicity stellar populations. But while much attention has been focused on their bright nebular gas emission, the massive stars that power it remain challenging to constrain. Here we present exceptionally deep Hubble Space Telescope ultraviolet spectra targeting six local (z < 0.02) galaxies that power strong nebular C iv emission approaching that encountered at z > 6. We find that the strength and spectral profile of the nebular C iv in these new spectra follow a sequence evocative of resonant scattering models, indicating that the hot circumgalactic medium likely plays a key role in regulating C iv escape locally. We constrain the metallicity of the massive stars in each galaxy by fitting the forest of photospheric absorption lines, reporting measurements driven by iron that lie uniformly below 10% solar. Comparison with the gas-phase oxygen abundances reveals evidence for enhancement in O/Fe 2–4 times above solar across the sample, robust to assumptions about the absolute gas-phase metallicity scale. This supports the idea that these local systems are more chemically similar to their primordial high-redshift counterparts than to the bulk of nearby galaxies. Finally, we find significant tension between the strong stellar wind profiles observed and our population synthesis models constrained by the photospheric forest in our highest-quality spectra. This reinforces the need for caution in interpreting wind lines in isolation at high redshift, but also suggests a unique path toward validating fundamental massive star physics at extremely low metallicity with integrated ultraviolet spectra.

Original content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 licence. Any further distribution of this work must maintain attribution to the author(s) and the title of the work, journal citation and DOI.

1. Introduction

Nearby star-forming dwarf galaxies beyond the Local Group are a crucial testbed for the physics of massive stars and gas at very low metallicities. The possible nature of these blue, H ii region–like galaxies as genuinely primordial systems captured during their first episodes of star formation was emphasized and debated soon after their discovery (e.g., Sargent & Searle 1970; Searle & Sargent 1972; Searle et al. 1973). A modern view paints these systems as different from true nascent galaxies in important ways, including their absolute mass scale and likely longer-term bursty star formation histories. While the debate continues regarding the precise differences with their high-redshift counterparts, metal-poor local dwarf galaxies remain the most accessible venue in which to empirically confront models for the very low-metallicity young stellar populations we expect to encounter at the highest redshifts.

The value of such rare very metal-poor dwarfs is particularly well illustrated by efforts to understand the strong C iv emission recently uncovered in the reionization era. In two of the first deep rest-ultraviolet (UV) spectra obtained for Lyα emitters at z ≳ 6, nebular emission in the resonant C iv λ λ1548, 1550 doublet is detected at implied doublet equivalent widths of 20–40 Å (Stark et al. 2015; Mainali et al. 2017; Schmidt et al. 2017). Strong limits placed on other UV lines in one of the systems support a stellar (over a power law) ionizing radiation source (Mainali et al. 2017), yet stellar models struggle to reproduce such prominent emission, only approaching the observed equivalent widths at extremely low metallicities. However, an empirical basis for this potential connection to very metal-poor stars remains elusive. Nebular emission in C iv is exceedingly rare at any strength in star-forming galaxies at lower redshifts, where this doublet is generally dominated by a broad P-Cygni profile powered in the winds of luminous OB stars (e.g., Prinja & Crowther 1998; Shapley et al. 2003; Steidel et al. 2016; Rigby et al. 2018). The canonical picture from observations of star-forming galaxies in the local universe with the initial complement of Hubble Space Telescope (HST) UV instruments supported this picture of C iv as a purely wind and interstellar medium (ISM) absorption feature (e.g., Leitherer et al. 2011). The prominent nebular C iv encountered in pathfinder z > 6 campaigns is a dramatic departure from this local context, and the resulting difficulty in interpreting this emission foreshadows potentially serious challenges in understanding rest-UV spectra at the highest redshifts with the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST).

Fortunately, the highly sensitive fourth-generation HST/Cosmic Origins Spectrograph (COS) has unveiled UV spectra of a dramatically different character than those found in previous local surveys. In particular, several HST/COS programs have now identified a population of star-forming galaxies with C iv in clear nebular emission alongside nebular He ii, at equivalent widths of ∼1–15 Å (Berg et al. 2016; Senchyna et al. 2017, 2019; Berg et al. 2019b, 2019a; Schaerer et al. 2022). These systems confirm that star-forming galaxies can power nebular C iv approaching the large equivalent widths observed at z > 6, but only at both sufficiently young effective ages (or high specific star formation rates; sSFRs) and extremely low metallicities (12 + logO/H ≲ 7.7; corresponding to Z/Z⊙ ≲ 10%), a parameter space occupied locally by primarily relatively low-mass galaxies missed by previous UV programs (Senchyna et al. 2019).

The establishment of this local reference sample of C iv emitters represents a unique opportunity to directly link high-ionization nebular emission to the fundamental properties of the underlying stellar populations, which are generally inaccessible at high redshift. However, several outstanding questions in the interpretation of these galaxies suggest our picture of them is not yet complete. While it is immediately clear that low gas-phase metallicities and young ages are a necessary condition for nebular C iv production in nearby star-forming systems, it is less obvious why galaxies with nearly identical Hβ equivalent widths and gas-phase metallicities would present such different C iv equivalent widths (Berg et al. 2019b; Senchyna et al. 2019). In addition, the significant gap between the largest C iv nebular emission equivalent width observed locally of 10–15 Å and the 20–40 Å emission measured at z > 6 is suggestive of potential differences between this reionization era population and these local metal-poor dwarfs of still unclear origin.

There is still a crucial quantity missing in our attempts to understand these findings: stellar metallicity. In a situation common to H ii regions and star-forming galaxies, strong optical nebular lines readily yield the gas-phase abundances of oxygen and nitrogen (and carbon through the UV C iii] line) as well as neon and argon, all of which except for nitrogen are α elements, synthesized and released mainly in intermediate-mass to massive stars on short timescales. However, iron and iron-peak elements play an outsized role in shaping the spectra of massive stars, whose numerous freed electrons and electronic transitions in the EUV–UV are crucial sources of opacity, especially near their surface wind-driving regions (e.g., Hubeny & Mihalas 2014; Vink 2021). The full promise of nearby star-forming galaxies as laboratories for studying young stellar populations and their impact on their environs cannot be fully realized without constraints on the stellar metallicity and in particular the stellar iron abundance.

Unfortunately, typical CNO gas-phase abundances tell us little about the total metallicity of the underlying massive stars. In contrast to the CNO and α elements, iron is released into the ISM for subsequent star formation mainly by Type Ia supernovae (SNe) which occur after a significant ∼ Gyr delay after a star formation episode. As a result, α/Fe ratios can be expected to vary dramatically with star formation history, generally decreasing significantly with time after a peak in star formation rate as α-rich yields from massive stars are slowly diluted by iron-rich Type Ia products. This is observed directly in the abundance patterns of individual stars in the Milky Way (MW), its satellites, and other Local Group galaxies (e.g., McWilliam 1997; Tolstoy et al. 2009). The natural expectation for assembling galaxies in the early universe which have just begun to form stars is thus a significant enhancement in α/Fe over the solar value, with magnitude dependent upon the uncertain contribution of Population III enrichment (e.g., Bromm & Yoshida 2011; Frebel & Norris 2015). An increasing number of reports suggest that such an enhancement is necessary to reconcile the low stellar metallicities relative to the gas-phase oxygen abundance inferred from observations of nebular emission and UV continuum light in massive galaxies at z ∼ 2 (e.g., Steidel et al. 2016; Strom et al. 2017; Sanders et al. 2020; Topping et al. 2020a; Cullen et al. 2021; Strom et al. 2022).

Despite this surge of interest at z ∼ 2, relatively little progress has been made in assessing the stellar abundances of extreme metal-poor star-forming galaxies nearby like the nebular C iv emitters. The optical absorption lines commonly used to assess stellar metallicities such as the Lick indices (e.g., Gallazzi et al. 2005) are washed out by light from the hot stars and nebular continuum dominating these high-sSFR systems, and regardless do not directly assess the abundances of the massive stars themselves. The gas-phase iron abundance can also be derived from collisionally excited lines of Fe iii–Fe v, but this is subject to significant systematic uncertainties in the ionization correction factors adopted and the assumed depletion onto dust (e.g., Izotov et al. 2006; Kojima et al. 2021; Berg et al. 2021). Another approach seeks to derive stellar metallicities based upon photoionization modeling of nebular lines with flexible stellar population synthesis models, where the leverage on [Fe/H] resides in the theoretical model-predicted changes in the shape of the ionizing spectrum with Z (e.g., Strom et al. 2017, 2018; Sanders et al. 2020; Runco et al. 2021). While insightful, these nebular-line-focused techniques remain indirect probes of the abundances of the massive stars themselves.

The most direct path toward stellar abundances in these systems is through their UV continuum light, and in particular, the photospheric iron lines encountered there (e.g., Bouret et al. 2003; Hillier et al. 2003; Rix et al. 2004). These lines probe iron in the atmospheres of the massive stars which dominate these galaxies and bypass the substantial modeling uncertainties inherent in the analysis of the stellar wind lines. Unfortunately, the generally single-orbit HST/COS spectra in which the strong nebular C iv emission was initially observed are too shallow to detect these blended absorption features; indeed, the target galaxies are often too low in metallicity for even the usually strong stellar P-Cygni wind profile in C iv to be detected in these spectra. To remedy this, we obtained new ultra-deep HST/COS G160M far-UV (FUV) spectroscopy with exposure times of 5–10 orbits per galaxy for six galaxies powering nebular C iv emission during HST Cycles 26 and 27. These new spectra provide a more detailed view of C iv and strong constraints on stellar wind and photospheric lines in the FUV continuum, allowing us to link this high-ionization emission to the fundamental properties of the underlying stellar populations.

This paper focuses on C iv and the stellar features in these new ultra-deep HST/COS spectra, and is organized as follows. In Section 2, we describe the target sample and derive constraints on their gas-phase metallicities and bulk stellar properties from their optical spectra. Section 3 presents the new HST/COS spectroscopic observations including their reduction and basic analysis. We describe our fits to the UV continuum with stellar population synthesis models to constrain the stellar metallicity in Section 4, and the results of these fits are presented in Section 5. Finally, we discuss these results in contexts ranging from local galaxy abundances to high-redshift nebular emission in Section 6, before summarizing and concluding in Section 7.

Unless otherwise stated, equivalent widths are reported as positive for emission and negative for absorption, and all logarithmic quantities presented herein should be assumed to be in base-10. When comparing with solar abundances, we adopt the composition assumed by our fiducial stellar population synthesis models from S. Charlot & G. Bruzual (in preparation, hereafter C&B; see Gutkin et al. 2016; Plat et al. 2019), which differ only slightly from the compilation adopted by the underlying parsec stellar evolution code as described in Bressan et al. (2012). In particular, this sets the present-day solar oxygen abundance at 12 + logO/H = 8.83 8 (corresponding to a gas-phase abundance with typical depletion of 8.71), solar iron at 12 + logFe/H = 7.52, and total metallicity at Z⊙ = 0.01524 (Caffau et al. 2008, 2011). 9

2. A Sample of Very Metal-poor Galaxies with Prominent Active Star Formation

While a population of nearby dwarf galaxies at 12 + logO/H < 8.0 and particularly high sSFR have been identified as sources of nebular C iv emission, the existing shallow HST/COS spectra of these galaxies preclude a detailed assessment of the stellar populations underlying this emission. We selected a sample of six of these local C iv emitters to follow up with deep FUV spectroscopy targeting both C iv and the photospheric signatures of their constituent massive stars. The target systems were selected from the HST/COS G140L samples assembled by Berg et al. (2016, hereafter B16) and Berg et al. (2019b, B19), and the G160M+G185M samples of Senchyna et al. (2017, S17) and Senchyna et al. (2019, S19), which together with Wofford et al. (2021) comprise the entire sample of local (z < 0.1) star-forming systems with reported nebular C iv detections. In particular, we selected our sample to include the two highest equivalent width nebular emitters in this doublet known locally at the time of the proposal (J104457 at 11 Å and HS 1442+4250 at 4 Å; S16; S19, see also Schaerer et al. 2022 who present two 10–15 Å detections at z = 0.3–0.4), two of the systems with the highest gas-phase metallicities still powering nebular emission in C iv (SB 2 and 82, at 12+logO/H ≃ 7.8–7.9; S17), and two metal-poor systems with extremely high equivalent width optical line emission yet relatively modest C iv equivalent widths < 4 Å (J082555 and J120202; B16; S17). These systems were targeted with HST/COS G160M/1533 spectroscopy with allocations of 5–10 orbits each over the course of two HST programs (GO:15646 and GO:15881, PI: Stark) which we describe in Section 3. The basic properties of this sample of C iv emitters are summarized in Table 1 and described in the remainder of this section.

Table 1. The Six Local Star-forming Systems Targeted for Deep G160M Spectroscopy

| Target | R.A. | Decl. | z | Distance | O32 | Hβ | E(B − V) |

| Optical |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | (J2000) | (J2000) | (HST/COS) | (Mpc, CF3) | W0/Å | int. (Gal.) | Source | ||

| J082555 | 08:25:55.52 | +35:32:32.0 | 0.0024 | 13 | 16.1 ± 1.6 | 264 ± 21 | 0.06(0.04) | 7.44 ± 0.04 | SDSS+Bok |

| SB 2 | 09:44:01.87 | −00:38:32.2 | 0.0049 | 21 | 7.3 ± 0.8 | 276 ± 11 | 0.15(0.05) | 7.81 ± 0.05 | SDSS+MMT (S17) |

| J104457 | 10:44:57.80 | +03:53:13.1 | 0.0129 | 57 | 18.1 ± 2.0 | 264 ± 21 | 0.08(0.04) | 7.48 ± 0.06 | SDSS+Bok |

| SB 82 | 11:55:28.34 | +57:39:51.9 | 0.0172 | 77 | 9.6 ± 1.0 | 175 ± 3 | 0.14(0.03) | 7.93 ± 0.04 | SDSS+MMT (S17) |

| J120202 | 12:02:02.49 | +54:15:51.0 | 0.0120 | 58 | 9.2 ± 0.4 | 271 ± 8 | 0.05(0.01) | 7.50 ± 0.03 | SDSS (BOSS) |

| HS1442+4250 | 14:44:11.47 | +42:37:35.5 | 0.0022 | 11 | 10.2 ± 0.5 | 113 ± 4 | 0.02(0.01) | 7.66 ± 0.04 | MMT (S19) |

Note. Included here are the target names: the coordinates of the region targeted with HST/COS in the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS) imaging frame; the redshift measured from the HST/COS spectrum; the corresponding luminosity distance estimated from Cosmicflows-3 (CF3; Graziani et al. 2019; Kourkchi et al. 2020); and gas-phase measurements of O32 ([O iii] λ4959 + λ5007/[O ii] λ3727 flux ratio, extinction corrected), the rest-frame Hβ equivalent width, and direct-Te oxygen abundance (see Section 2.1 and 2.2).

Download table as: ASCIITypeset image

2.1. Gas-phase Conditions and Metallicities

The optical nebular emission lines provide key insight into the properties of the ionized gas in these galaxies including the abundance of oxygen in the gas phase. This is of particular interest as a point of comparison in the stellar abundance analysis that the new ultraviolet data enables. Leveraging the detections of the auroral [O iii] λ4363 line for all six, we derive a self-consistent set of gas-phase oxygen abundances via the direct-Te method (following the general procedure described also in S17 and S19). For this analysis we rely on the designated sciencePrimarySDSS spectrum for all of the targets except for HS 1442+4250 which does not have an SDSS spectrum. In this case, we rely instead on the MMT Blue Channel spectrum described in S19. First, we measure the flux and equivalent width of the necessary optical lines by fitting a Gaussian (or pair thereof for close doublets) plus linear local continuum model to each, using emcee (Foreman-Mackey et al. 2013) to compute the uncertainties on the fit parameters. The fluxes of these lines are corrected for reddening, first Galactic (using the Schlafly & Finkbeiner 2011 reddening map and assuming a Fitzpatrick 1999 reddening law) and then intrinsic assuming a Small Magellanic Cloud (SMC) extinction curve (Gordon et al. 2003). We use the pyneb library to derive constraints on the gas parameters of interest from these line measurements. 10 In particular, we adopt a standard two-zone H ii region model, computing the Te and ne relevant for the O+ and O2+ regions through cross convergence of the ne -sensitive S ii λ λ6731, 6716 ratio with the Te -sensitive ([O ii] λ λ3726, 3729, 11 [O ii] λ λ7320, 7330) and ([O iii] λ4363, [O iii] λ5007) ratios (respectively). The exception to this procedure is HS 1442+4250 for which [O ii] λ λ7320, 7330 is undetected in our MMT spectrum; in this case, we instead rely on the empirical relationship between Te (O II) and Te (O III) derived for metal-poor galaxies by Izotov et al. (2006) to estimate the temperature of the lower-ionization region. We estimate uncertainties in the final quantities of interest by bootstrap resampling the Gaussian line flux uncertainty distributions and recalculating all quantities of interest (with line ratio combinations recognized as invalid by pyneb according to our adopted atomic data discarded).

In addition to the primary SDSS and MMT spectra, these gas-phase measurements must also in four cases rely on shallow bluer spectra to obtain measurements of the [O ii] λ3727 doublet which remains below the 3800 Å blue cutoff of the original SDSS I/II spectrograph at these low redshifts (z < 0.02). 12 Specifically, SB 2 and 82 have [O ii] constraints from MMT Blue Channel spectra described in S17. We also rely on new Bok spectra to constrain [O ii] λ3727 for J082555 and J104457; both were observed with the Bok B&C spectrograph and the 300 g mm−1 grating (spanning 3500–7500 Å) with 3 × 15 minutes integrations on 2021 March 3. These data were reduced using standard longslit techniques in IRAF. As done also for the supplementary MMT spectra, we translate the measured [O ii] doublet flux measured in the Bok spectra to the SDSS flux scale by applying a correction derived from the ratio of the strong optical lines in common between the SDSS and Bok spectra, and adopt a conservative uncertainty of 10% in this rescaled doublet flux.

The resulting direct-Te oxygen abundances (Table 1) confirm that these C iv emitters harbor very metal-poor gas. The values range from 12 + logO/H = 7.44 in the lowest-metallicity case (J082555) up to 7.93 in the highest (SB 82). This corresponds to a range of 5%–15% of the solar photospheric oxygen value, with all but SB 2 and SB 82 falling below 10% and thus in the realm of designated extremely metal-poor galaxies (XMPs). Since these are measured in essentially the same way and with the same data as in S17 and S19, the metallicity measurements are by construction in very good agreement with those results. Our metallicity estimates are slightly different from those presented in B16 for J082555 (0.07 dex higher) and J104457 (0.03 dex higher), and from B19 for J120202 (0.13 dex lower). We attribute these generally small discrepancies to differences in our assumed atomic data and methodology (most significantly, our uniform [O ii] λ3727 access and our choice to estimate Te ([O ii]) from the [O ii] λ7325/λ3727 ratio).

We also measure uniformly large flux ratios O32 ([O iii]λ4959 + λ5007/[O ii] λ3727, after extinction correction) of 7–18, and generally very prominent gas emission relative to the stellar continuum with Hβ at (rest-frame) equivalent widths 13 of 113–276 Å. Together, these measurements paint a picture of systems dominated by recently formed stars with strong ionizing continua.

2.2. Bulk Stellar Properties

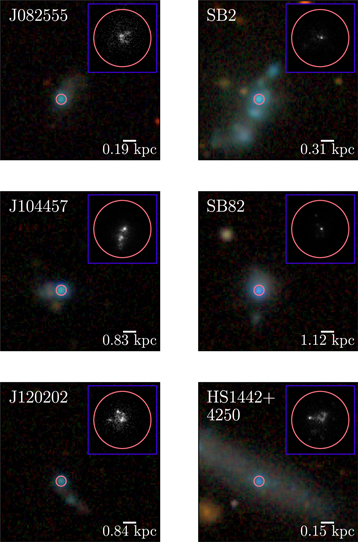

The optical spectroscopy and imaging (Figure 1) for these systems provide quantitative constraints on the age and mass of stars formed in their recent dominant star formation event. This can act as a valuable prior in the interpretation of the UV spectra that we will focus on in the remainder of this paper. To extract these optical constraints, we first measure 3″ diameter aperture photometry (corresponding approximately to the HST/COS 25 diameter aperture convolved with the median SDSS rband seeing of 1

3) in all five (

) SDSS broadband mosaics for each source centered on the spectroscopic target. We then fit these fluxes with beagle (Chevallard & Charlot 2016) alongside the equivalent width of Hβ measured in the optical spectrum for each. Together with the strong band contamination in

) SDSS broadband mosaics for each source centered on the spectroscopic target. We then fit these fluxes with beagle (Chevallard & Charlot 2016) alongside the equivalent width of Hβ measured in the optical spectrum for each. Together with the strong band contamination in  and

and  produced by the [O iii] and Balmer lines at these low redshifts, these measurements provide constraints on both the total stellar mass and SFR of the current star formation event. The models employed here are the same as those used to fit the UV continuum described below (Section 4.1), but with an initial mass function (IMF) upper-mass cutoff of 300 M⊙ (minimal differences were found between the 300 and 600 M⊙ models in the photospheric metallicity results presented in Section 5) and with nebular emission lines included so as to self-consistently account for the strong line contributions in the optical broadbands. We perform this modeling assuming both a constant star formation history with variable age (or start time) and a simple (single, variable age) stellar population, representing two approximations of a recent “burst” of star formation (see also Section 4.1). In both cases we adopt uniform priors for the two corresponding star formation history parameters: age (allowed to vary from 1 to 100 Myr) and stellar mass (up to 109

M⊙). We allow the tied stellar and gas-phase metallicity (0.006–1.0 Z⊙), nebular

produced by the [O iii] and Balmer lines at these low redshifts, these measurements provide constraints on both the total stellar mass and SFR of the current star formation event. The models employed here are the same as those used to fit the UV continuum described below (Section 4.1), but with an initial mass function (IMF) upper-mass cutoff of 300 M⊙ (minimal differences were found between the 300 and 600 M⊙ models in the photospheric metallicity results presented in Section 5) and with nebular emission lines included so as to self-consistently account for the strong line contributions in the optical broadbands. We perform this modeling assuming both a constant star formation history with variable age (or start time) and a simple (single, variable age) stellar population, representing two approximations of a recent “burst” of star formation (see also Section 4.1). In both cases we adopt uniform priors for the two corresponding star formation history parameters: age (allowed to vary from 1 to 100 Myr) and stellar mass (up to 109

M⊙). We allow the tied stellar and gas-phase metallicity (0.006–1.0 Z⊙), nebular  (−4–−1), and dust attenuation (assuming an SMC curve,

(−4–−1), and dust attenuation (assuming an SMC curve,  –2) to vary over their respective uniform priors.

–2) to vary over their respective uniform priors.

The absolute magnitude of the mass and star formation rates derived from this fitting depend upon the assumed luminosity distance to these targets. While fortunately our analysis does not depend strongly on the exact value of these stellar masses or thus this distance, it is important to note that at very low redshifts z < 0.01 (corresponding to velocities <1000 km s−1) peculiar motions begin to approach and potentially exceed the velocity of the Hubble flow. Without a means of more robust distance measurement, our best option remains a comparison of the measured redshifts to a model for the peculiar velocity field in the local universe. We update our distance estimates in this analysis to the Cosmicflows-3 local flow model (Graziani et al. 2019; Kourkchi et al. 2020), first converting our heliocentric redshifts to the Local Sheet reference frame (Tully et al. 2008; Kourkchi et al. 2020) and then obtaining the corresponding distance from the smoothed Cosmicflows-3 model (none of our objects were found to have multiple degenerate solutions). The distances thereby obtained are displayed in Table 1. Differences from previous estimates relying on other local flow models are generally small. With respect to the published distances of S17 and S19 in particular, we find changes of ≤2 Mpc (≲10%) for SB 2, SB 82, and HS 1442+4250.

The resulting measurements of the effective young stellar population age and (distance-dependent) stellar mass within the spectroscopic aperture are presented in Table 2. These fits confirm that the broadband data for these systems are consistent with low-mass stellar populations ∼ 104–106 M⊙ with young effective ages in the range of 3–22 Myr assuming a constant star formation history or 2–3 Myr assuming a single-age stellar population, both of which are able to reasonably match the photometric data and Hβ equivalent widths. However, a more detailed view of the massive stars present requires deep UV spectra.

Table 2. beagle SED Fits to the Broadband SDSS ugriz Photometry

| Target | CSFH | SSP | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name |

| t/Myr |

| t/Myr |

| J082555 | 4.03 ± 0.03 |

| 4.25 ± 0.05 |

|

| SB2 | 5.14 ± 0.02 |

| 5.35 ± 0.01 |

|

| J104457 | 5.53 ± 0.02 |

| 5.67 ± 0.02 |

|

| SB82 | 6.29 ± 0.02 |

| 6.69 ± 0.01 |

|

| J120202 | 5.17 ± 0.21 |

| 5.22 ± 0.04 |

|

| HS1442+4250 | 4.60 ± 0.02 |

| 4.61 ± 0.03 |

|

Note. The BEAGLE fits naturally account for nebular line contamination to the broadband photometry; this contribution is additionally constrained by the explicit inclusion of the measured Hβ equivalent widths in the fits. We include the stellar mass and age assuming both a constant star formation history with variable start and a single-age stellar population model for the young stellar component that dominates the optical and UV for these systems.

Download table as: ASCIITypeset image

3. Ultra-deep COS Spectroscopy

In this section, we first summarize the new FUV spectroscopic observations we have obtained, designed to deliver detailed constraints on the massive stars in these C iv emitters (Section 3.1 and described in more detail in Appendix A). Then, we provide an overview of these new spectra and the strength of nebular and stellar features derived therefrom (Section 3.2) before proceeding to describe the detailed continuum fitting we perform in Section 3.1.

3.1. Summary of Observations

New extremely deep spectra of the six target C iv emitters were obtained for the target systems in two GO programs (proposal IDs 15646 and 15881, PI: Stark) selected and executed as part of Cycles 26 and 27. All of the spectroscopic observations for both programs were made using the new G160M/1533 Å central wavelength setting introduced in Cycle 26 (e.g., Fox et al. 2019). This setting produces spectra spanning 1339–1710 Å with the FUVA/FUVB detector gap at 1520–1530 Å, which at the low redshifts < 0.02 of our targets (Table 1) allows us to simultaneously access the C iv λ λ1548, 1550 and He ii λ1640 nebular and stellar wind complexes alongside the wind and photospheric complexes at ∼1350–1500 Å.

Given the uncertain nature of the strength of the target continuum features at these low metallicities, we allotted a uniform 10 (GO:15646) or 5 (GO:15881) orbits in total to each system. These exposure times were designed to ensure a minimum signal-to-noise (S/N) ratio per-resolution element (resel; 6 pixels, or 0.07 Å for G160M) of 10 (corresponding to S/N > 30 per Å). A detailed accounting of the observing strategy and calibration procedures is provided in Appendix A. In summary, the observations were conducted over the course of 16 visits total, including visits lost to guide star acquisition issues and those scheduled as repeats (summarized in Table 3). We used calcos to combine and calibrate all of the successful observations for each object. Our results confirm the appropriateness of the standard extraction techniques for these targets, but we derive a correction factor for the formal calcos uncertainties which we find are likely overestimated for the faint continuum sources in our sample.

Table 3. HST/COS UV Spectroscopic Observations

| Target | Proposal/ | Visits | Fλ (1450Å) | Total Exposure | S/N(1450 Å) per resel (0.07 Å) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Program ID | (UT start) | ×10−15 erg/s/cm2/Å | Time (s) | (calcos reported) | (corrected) |

| J082555 | GO:15881/LE4Z | 01 (2020-03-01) | 1.16 | 12869 | 8.4 | 12.5 |

| 02 (2020-04-24) | ||||||

| 03 (2020-02-18)‡ | ||||||

| 53 (2020-03-30)† | ||||||

| SB2 | GO:15646/LDXT | 03 (2020-04-05) | 0.87 | 26925 | 10.8 | 14.9 |

| 04 (2020-04-06) | ||||||

| J104457 | GO:15646/LDXT | 07 (2020-05-18) | 1.55 | 26365 | 15.7 | 21.0 |

| 08 (2020-04-07)† | ||||||

| SB82 | GO:15646/LDXT | 01 (2019-11-21) | 3.51 | 29256 | 24.0 | 28.2 |

| 02 (2019-11-21) | ||||||

| J120202 | GO:15881/LE4Z | 04 (2020-04-26) | 1.05 | 13498 | 7.7 | 10.9 |

| 05 (2020-04-26) | ||||||

| 06 (2020-04-12) | ||||||

| HS1442+4250 | GO:15646/LDXT | 05 (2019-10-11) | 2.08 | 27137 | 18.6 | 24.7 |

| 06 (2019-10-09)† | ||||||

| 56 (2019-12-26) | ||||||

Note. All executed visits are listed for each object and for the entirety of both proposals (GO:15646 and GO:15881). Visits with an exception report (some of which did not yield useful data as a result) are indicated with a † and discussed in Section 3; the one visit during which usable spectroscopic data was not taken at all is marked with a ‡. The final columns list the S/N per-resolution element (6 pixels, or ∼0.073 Å) averaged near 1450 Å both as initially reported by calcos in the reduced one-dimensional spectrum, and after correction based upon the observed scatter in the continuum (see text).

Download table as: ASCIITypeset image

The final combined and corrected G160M spectra all exceed the target S/N of 10 per resel at 1450 Å, sufficient for a detailed investigation of the stellar continuum in these extreme C iv emitters.

3.2. Overview of the New Spectra

In this section we provide a broad overview of the new, deep view of both ionized gas and the underlying massive stars that the new HST/COS spectra afford.

The most striking feature dominating the new G160M/1533 spectra of all six targets is the extraordinarily strong nebular emission from highly ionized gas species on which these galaxies were selected. Both components of the semiforbidden O iii] λ1661, 1666 doublet, the He ii λ1640 recombination line, and the C iv λ λ1548, 1550 resonant doublet are detected in all six systems. We fit these lines individually with Gaussians after rebinning the spectra to one resolution element (six pixels). Comparison with the vacuum wavelengths of these transitions yields the new systemic redshift measurements for our systems presented in Table 1 and utilized throughout our analysis. We find a small <10 km s−1 (≲1%) error in this redshift measurement based on the line-to-line variation and the formal fitting uncertainties in the central wavelengths, and thus the uncertainties in these redshifts are likely close to the uncertainty in the medium grating wavelength calibration of 15 km s−1 (Hirschauer et al. 2021). Measurements of these line fluxes are presented in Table 4.

Table 4. UV Nebular Emission Line Measurements and Stellar Absorption Indices

| Target | C iv λ1549 | Nebular Line Fluxes (10−15 erg/s/cm2) | Stellar Index Equivalent Widths (integrated, Å) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Nebular W0/Å | C iv λ1549 | He ii λ1640 | O iii] λ1661 | O iii] λ1666 | C iv λ1549 (P-Cygni) | Bl1425 | Fe1453 |

| J082555 | 2.14 ± 0.17 | 2.19 ± 0.16 | 0.15 ± 0.07 | 1.35 ± 0.09 | 2.83 ± 0.10 | −0.22 ± 0.18 | 0.02 ± 0.09 | 0.24 ± 0.13 |

| SB2 | 0.77 ± 0.12 | 0.66 ± 0.10 | 1.25 ± 0.06 | 1.50 ± 0.12 | 3.08 ± 0.13 | −0.53 ± 0.11 | −0.21 ± 0.08 | −0.41 ± 0.10 |

| J104457 | 10.60 ± 0.48 | 15.57 ± 0.45 | 3.12 ± 0.16 | 2.92 ± 0.13 | 7.13 ± 0.16 | 0.37 ± 0.09 | 0.24 ± 0.07 | −0.27 ± 0.07 |

| SB82 | 1.23 ± 0.08 | 3.67 ± 0.21 | 1.46 ± 0.10 | 2.19 ± 0.10 | 5.81 ± 0.14 | −2.37 ± 0.06 | −0.48 ± 0.05 | −0.77 ± 0.05 |

| J120202 | 1.46 ± 0.14 | 1.26 ± 0.11 | 0.67 ± 0.08 | 0.84 ± 0.07 | 2.02 ± 0.08 | 0.01 ± 0.17 | −0.12 ± 0.12 | −0.14 ± 0.13 |

| HS1442+4250 | 3.87 ± 0.11 | 7.09 ± 0.18 | 2.88 ± 0.07 | 1.40 ± 0.10 | 2.99 ± 0.10 | −0.54 ± 0.08 | −0.53 ± 0.04 | −0.64 ± 0.06 |

Note. Measured in the new G160M spectra. Nebular emission in C iv, He ii, and both O iii] components are detected in all six targets, and constraints on the integrated equivalent width of several key broad stellar absorption indices are also presented.

Download table as: ASCIITypeset image

These new deep FUV spectra are especially notable for providing an exquisite view of the multicomponent high-ionization C iv doublet, illustrating the power of deep UV spectra to probe the detailed physics of star-forming galaxies. While all of the targets were selected on the identification of nebular C iv emission in archival HST/COS spectra, these shallower spectra did not provide a complete picture of this doublet. In particular, J082555 and J120202 were previously only observed with the low-resolution COS/G140L grating in the FUV which affords nearly an order of magnitude lower spectral resolution than G160M, precluding clear disentanglement of the nebular emission profile from interstellar absorption. In addition, the broad (>1000 km s−1) and metallicity dependent stellar wind contribution to this complex was generally too weak to be confidently detected in the single-orbit spectra obtained previously for this metal-poor galaxy sample (though see Senchyna et al. 2019), leaving us with minimal information about the massive stars underlying this emission.

Figure 1. Optical g, r, i (RGB) SDSS images centered on our targets, with the 25 diameter HST/COS aperture indicated by a red circle centered on the target u-band centroid. An inset panel for each target displays one of the HST/COS NUV target acquisition images obtained for each, on a linear scale. A 3″ scalebar is also shown and labeled with the corresponding distance in comoving Mpc at the estimated distance of each target (Table 1).

Download figure:

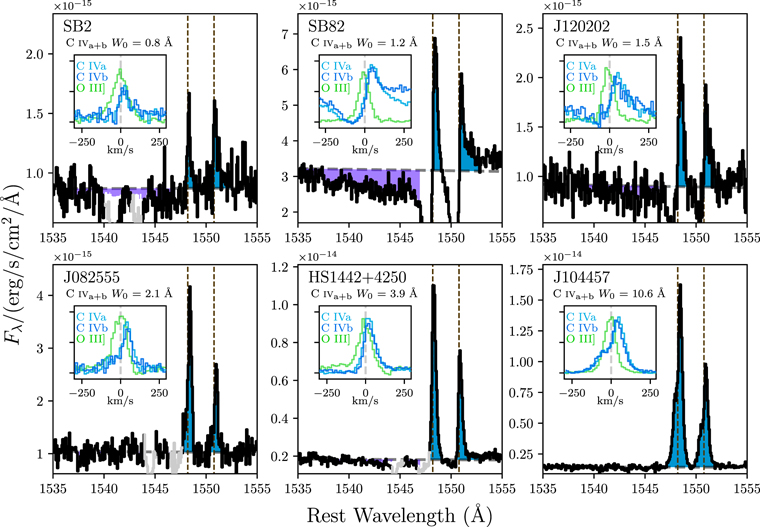

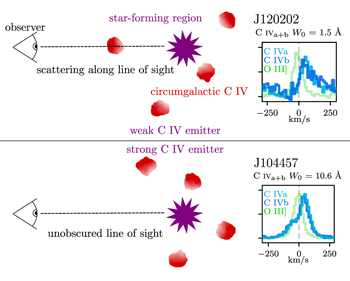

Standard image High-resolution imageWe plot the new very high-S/N G160M C iv profiles obtained for all six target systems in Figure 2. All show very clearly detected emission in both components of the doublet. We directly integrate this emission for each component separately after first fitting and subtracting off any visible absorption components of MW and systemic C iv, yielding equivalent width measurements ranging from 0.8 to 10.6 Å (Table 4). In addition to finding stronger emission than previously reported for J082555 and J120202 (S19; B19), we detect clear evidence for non-Gaussianity in the narrow profiles of C iv in all six targets. To illustrate this, an inset panel for each spectrum is included in Figure 2 displaying the velocity profile of both C iv components and O iii] λ1666 for comparison (with redshift determined jointly from the O iii] and He ii lines in the same spectra). In all cases, the C iv profiles show structure not evident in the O iii] emission, with peaks of emission uniformly redder than the theoretically expected wavelengths.

Figure 2. The new ultra-deep spectra presented in this paper provide a clear view of the C iv λ λ1548, 1550 complex, here ordered by the total equivalent width of nebular emission in this doublet (as indicated) and plotted after binning to 2 resels. The rest wavelengths of the two transitions are indicated by vertical dashed lines, and the redshift has been determined using joint fits to the O iii] λ λ1661, 1666 doublet, and He ii λ1640 line in the same spectrum. Stellar P-Cygni absorption is clearly detected in several of the targets and indicated by purple shading, while the nebular emission is highlighted in blue; the spectrum is shaded light gray at wavelengths impacted by intervening MW C iv absorption. Inset panels show a comparison between the profiles of the two narrow C iv components and O iii] λ1666 in velocity space. All six emit strongly (at 1–11 Å combined equivalent width) in this resonant doublet, indicative of a significant quantity of hot and highly ionized gas. However, a sequence is apparent from purely redshifted emission and blueshifted absorption in the lowest equivalent width emission profiles to broad and sometimes double-peaked emission in the most prominent emitters, likely a signature of resonant scattering.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageIntriguingly, this velocity structure in the narrow C iv profiles appears to correlate with the measured strength of emission in this doublet. The weakest nebular C iv emitters in the sample (<2 Å, top row of Figure 2) all show strongly redshifted emission, with either negligible emission or strong absorption blueward of zero velocity (P-Cygni features on the scale of 100–250 km s−1). In contrast, the three strongest emitters (bottom row) show no strong blue-side absorption and include two cases of double-peaked emission profiles (J082555 and J104457; the latter already noted and discussed extensively by Berg et al. 2019a). The detection of such a sequence, evocative of that followed by Lyα (Verhamme et al. 2006), strongly suggests that the C iv in these local systems is subject to resonant scattering in its escape from these galaxies (as argued by Berg et al. 2019a). We discuss the consequences of this point in more detail in Section 6.1.

The C iv profiles shown in Figure 2 also illustrate the power of these spectra to unveil features encoded directly in the stellar continuum. Strong stellar P-Cygni absorption is detected in SB 82 at −2.4 Å equivalent width in depth and in SB 2 and HS 1442+4250 with equivalent widths of −0.5 Å (Table 4; integrated from 1530 to 1550 Å after subtracting Gaussian fits to the ISM/MW and nebular lines and with linear continuum determined in the windows [1490, 1520] and [1560, 1590] Å). The other three systems with lower gas-phase metallicities are not formally detected via this full absorption trough integration at their achieved S/N (Table 4), but hints of broad stellar absorption at <1 Å EW in depth are still visible in their spectra (see also Figure 11). This high-velocity P-Cygni feature is produced by outflowing gas in the expanding atmospheres of the massive O stars powering the UV continuum in these galaxies. At the low metallicities of these systems, these metal line-driven stellar winds and their spectral signatures are usually far too weak to be detected in typical UV spectra. These spectra thus place some of the strongest and only constraints to date on the winds of massive stars below the metallicity of the Magellanic Clouds where individual stars can be studied en masse.

In addition to information about uncertain winds, the stellar continuum in these deep UV spectra also provides a rarefied view of photospheric absorption in the underlying OB stars, which yields direct leverage on the stellar metallicity. As a first attempt at quantifying this absorption, we measure and report the strength of several relatively broad indices probing stellar features that are commonly measured especially in low-S/N and low-resolution spectra of star-forming galaxies. In particular, we measure the Bl1425 and Fe1453 indices defined by (Fanelli et al. 1992, see also Vidal-García et al. 2017) which are dominated by many stellar photospheric lines of Fe v and in the former case, also Fe iv, C ii λ1429, and Si iii λ1417. In a similar pattern to the C iv P-Cygni strengths, we find strong absorption detections of 0.5–0.8 Å EW in depth in SB 82 and HS 1442+4250, weaker absorption in SB 2 of 0.2–0.4 Å, and a range of absorption largely ≲0.2 Å in magnitude and often undetected in these broad indices in the remaining three spectra of the lowest-O/H systems (Table 4).

These initial empirical measurements of the stellar continuum already show clear evidence for a range of stellar absorption strengths, potentially indicative of a significant spread in metallicities. At first impression, this trend appears broadly in line with the metallicity trend found in the gas-phase oxygen abundances. However, quantitative comparison of the new deep UV spectra to stellar models is necessary to extract robust constraints for comparison. At the high S/N and dispersion achieved in our spectra, our analysis can take advantage of a more detailed continuum comparison than usually possible, which is especially important in the low-metallicity regime where the very broad stellar indices just presented show relatively low dynamic range with variations in metallicity (e.g., Vidal-García et al. 2017). Section 4 is devoted to describing the model comparison methodology adopted in this work.

4. Ultraviolet Continuum Fitting

The ultraviolet continuum of star-forming galaxies is dominated by light that has been imprinted on by the photospheres and expanding atmospheres of massive OB stars. The resulting pattern of emission and absorption from various atomic species provides direct insight into the fundamental properties of the composite stellar population responsible for this light, including crucially the stellar iron content—both directly via the strength of photospheric absorption lines of ionized iron, and indirectly through the strength of wind features produced by the iron line-driven winds. In order to extract constraints on this metallicity and other stellar population properties, it is necessary to compare these patterns to composites of model stellar atmospheres. In this section, we describe our approach to this model comparison first by describing the stellar population model framework we utilize, followed by our description of the fitting procedure we follow to constrain the parameters describing this composite population.

4.1. Stellar Population Synthesis Models

First we must choose a set of stellar population synthesis models to which our deep UV continuum constraints can be compared. We choose to focus on the updated Bruzual & Charlot (2003) models (C&B), which have been iteratively improved since described by Gutkin et al. (2016). We refer the reader to Plat et al. (2019) for a more thorough description of the current state of these models, choosing here to highlight the details most pertinent to our continuum fitting analysis. While we focus on C&B, we also repeat our analysis with minor modifications for Starburst99 (hereafter S99; Leitherer et al. 2014) as well; these fits and results are described in Appendix B.

4.1.1. Stars

These evolutionary tracks followed by massive stars and the atmosphere models assigned to them on this journey are the most crucial ingredients shaping the emergent stellar features. The C&B models are underpinned by evolutionary tracks from the PAdova and TRieste Stellar Evolution Code (parsec; Bressan et al. 2012; Chen et al. 2015) which are used to predict the evolution of stars up to initial masses of 600 M⊙ from Z = 0.0001 up to 0.040 (corresponding to Z/Z⊙ = 0.0066–2.6). These models include modern treatments of mass loss and the Wolf–Rayet (WR) phase appropriate for such massive stars (Vink et al. 2011; Chen et al. 2015), extending to much lower metallicities than have previously been employed in such calculations. As described in (Plat et al. 2019, their Appendix A), these predictions have accordingly been coupled with updated high-resolution fully theoretical WR atmosphere models from the Potsdam WR group (PoWR; e.g., Todt et al. 2015, and references therein). This library provides line-blanketed, non-LTE, spherically expanding atmosphere predictions extensible to WNE, WNL, WC, and WO spectral types down to sub-SMC metallicities. It is important to note that these models generate WR and similar stars only through wind-driven mass loss, neglecting their expected production through binary mass transfer (e.g., Eldridge & Stanway 2009; Götberg et al. 2018, see also the discussion in Senchyna et al. 2021).

Next these stellar tracks and atmospheres are used to construct composite SSP spectral models. The C&B models are provided on a uniform moderate-resolution wavelength grid of 0.5 Å steps over the FUV and at 135 ages from 104 to 108 years, which we retain for comparison to the observed spectra. We adopt a Chabrier (2003) IMF and an upper-mass cutoff of 600 M⊙. This choice in maximum initial mass reflects the possibility that especially at very low metallicity where gas cooling is inefficient and wind-driven mass loss minimal, binary mass transfer and mergers may produce stars with masses well in excess of canonical limits (e.g., Schneider et al. 2014; Vink 2018). Conducting our analysis with both the Mup = 300 and 600 models suggests that for the current treatment in the C&B models, differences in the photospheric lines and related metallicities are not significantly impacted by this decision.

Finally, an assumption about the star formation history must be made to produce a composite spectrum. We consider both a constant star formation history (CSFH) starting at variable time t and combinations of single-age stellar populations (SSPs) to represent the young stellar populations underlying the FUV continuum. These star formation histories represent two extremes of approximation for the young stellar populations present in these galaxies. Comparing the results of both allows us to examine the spectral impact of different mixtures of young stellar populations resulting from potentially bursty recent star formation. While older generations of stars are likely present in these galaxies and unaccounted for in these young star formation histories, since they will not contribute significantly to the UV, we do not consider more temporally extended parameterizations that would include them. We explore the results of both choices in more detail below, but consider the CSFH results as our fiducial products.

4.1.2. Nebular Emission

At the young ages of these star-forming complexes, the contribution of the nebular continuum to the FUV is non-negligible, reaching up to ∼50% of the total continuum at 1450 Å at the lowest metallicities Z ≲ 0.001 and youngest ages ≲2 Myr. This additional radiation dilutes the stellar continuum and must be taken into account when analyzing the strength of stellar absorption features in such observed spectra. In the range of the considered FUV wavelengths, the nebular continuum emission is dominated by two-photon decay from the first excited state of hydrogen along the forbidden 2s → 1s pathway, with a much smaller contribution from free-bound recombination to the first excited state (Draine 2011). To account for this addition to the UV light, we utilize the nebular continuum predictions of the cloudy models (Ferland et al. 2017) computed self-consistently alongside the C&B stellar models. We use the standard ionization-bounded predictions and gas-phase abundances described by Gutkin et al. (2016) and Plat et al. (2019). We fix the gas density nH to 102 cm−3 (close to the median of 190 cm−3 we find from the optical S ii doublet in metallicity calculation), the dust-to-metal mass ratio ξd to 0.3 (which is close to the solar value: Gutkin et al. 2016), and the volume-averaged ionization parameter  to −2.5. This cloudy calculation also includes dust attenuation from the dust internal to the H ii regions computed in a physically consistent way which we apply to the stellar continuum. We effectively assume throughout that the stellar and nebular continua are both subject to the same dust column (i.e., we assume no differential reddening of the stellar continuum). This is likely appropriate for the very young stellar populations considered herein, which are unlikely to have dispersed significantly and are predominantly cospatial with the nebular emission they have excited (e.g., Charlot & Longhetti 2001; Senchyna et al. 2021).

to −2.5. This cloudy calculation also includes dust attenuation from the dust internal to the H ii regions computed in a physically consistent way which we apply to the stellar continuum. We effectively assume throughout that the stellar and nebular continua are both subject to the same dust column (i.e., we assume no differential reddening of the stellar continuum). This is likely appropriate for the very young stellar populations considered herein, which are unlikely to have dispersed significantly and are predominantly cospatial with the nebular emission they have excited (e.g., Charlot & Longhetti 2001; Senchyna et al. 2021).

For the purposes of this analysis, these nebular parameters are fixed to the above values and the nebular continuum with no emission lines is simply added to the stellar continuum for each SSP spectrum. We refer the reader to Appendix C.2 for an exploration of the effect of varying these nebular parameters on our results.

4.2. Spectra Comparison and Fitting

With stellar models assembled, we proceed to comparison with the observed FUV spectra. In this paper we are primarily interested in leveraging the information encoded in the forest of FUV photospheric absorption lines, which directly access ionized species including iron in the atmospheres of the massive stars present. We accomplish this through direct comparison of the measured spectra to the models, taking full advantage of the resolution and wavelength coverage of the ultra-deep spectra. To minimize the confounding effects of extinction (potentially a source of significant systematic uncertainty in the FUV even at the modest E(B − V) values of our sample; Table 1), we perform all of this model comparison in continuum-normalized space. In this subsection we describe the processing both the observed and model spectra undergo, and the Bayesian model comparison we then perform to extract constraints on the key model parameters of interest. We present and discuss the results of this fitting in the following sections.

First, we must ensure that the data and model comparison only include features that we wish to compare. Most crucially, the data are impacted by nebular line emission (Section 3.2), as well as narrow gas absorption lines both from surrounding or outflowing gas at the galaxy systemic redshift as well as from the MW halo (notably strong lines of Al ii, C ii, C iv, Si ii, Si iv, and Fe ii) which must be excluded if we are to compare the stellar continuum cleanly. We conservatively mask ±1.5 Å around the expected wavelength of each of these transitions, with wavelengths taken from the NIST Atomic Spectra Database 14 and the literature where appropriate, which we find is well beyond their typical measured width and is sufficient to remove them from consideration. We also mask the 1–2.5 Å closest to the FUV chip edges, which tend to be noisier and suffer from some residual calibration artifacts.

Our primary focus is on the photospheric lines, but the deep constraints on the winds lines provide important information about the massive stars present as well. In model comparison we choose to always mask the stellar wind lines O v λ1371 and Si iv λ λ1393, 1402; O v has generally poor morphological agreement between the data and models, and Si iv is strongly impacted by difficult-to-clean interstellar absorption. We generally also mask generously around the C iv λ λ1548, 1550 and He ii λ1640 wind lines as well, but the wings of the C iv and He ii wind profiles beyond the central regions impacted by nebular emission are in contrast straightforward to compare (and we include the uncontaminated portions of the C iv profile in some fits as described below).

Next, both the observed and model spectra must be continuum normalized in a self-consistent way. In both cases, we fit a cubic spline to the wavelength region from 1310–1710 Å (encompassing the rest-wavelength span of all of the G160M/1533 spectra presented here) after masking the strong wind lines (and other gas lines in the case of the observed spectra), with intermediate knots placed at in the relatively clean continuum at rest frame 1450 and 1590 Å. This common procedure ensures that data comparison occurs in a common normalized flux frame, but we also include a nuisance parameter in our fitting to account for a potential residual constant offset.

The actual model comparison proceeds as follows. First, the normalized model spectrum is assembled from the specified stellar metallicity and age (or other star formation history parameters). We linearly interpolate the flux in continuum-normalized space between the gridpoints so that the predicted flux is continuous in Z and t. Then, the raw continuum-normalized spectral data is corrected to the rest frame by redshift zadopt = fz z, where z is the systemic redshift estimated from the UV nebular emission lines in the same spectrum (Table 1) and fz is a free model parameter accounting for potential uncertainties in this correction. To account for the different spectral resolutions of the data and model spectra, the data are then smoothed by a Gaussian filter whose size σs in COS spectral pixels is allowed to vary as another free parameter. We then median-bin the data onto the model wavelength grid over the region of interest, with masked regions ignored. The uncertainties on the binned data are computed in the usual way, but with variance adjusted by a fractional amount fvar:

This variable fvar thus accounts for the possibility that our (already revised downwards; see Appendix A) COS spectral uncertainties might underestimate the real error. Our Bayesian likelihood function  assuming uncorrelated Gaussian uncertainties is then given as (modulo a constant)

assuming uncorrelated Gaussian uncertainties is then given as (modulo a constant)

where δ y is the freely varying constant adjustment to the model continuum normalization, and all fluxes F and uncertainties thereon σF are continuum-normalized quantities.

In total, we now have a model for our continuum-normalized spectrum consisting of ≥6 parameters Θ:

- 1.First, the ≥1 parameters describing the star formation history. This is simply the effective stellar population age

in the case of a CSFH or SSP alone. We either allow this quantity to vary over a uniform prior spanning the model age grid, or (as discussed below) assume a narrow Gaussian prior (σ = 0.1 dex.) fixed to the values derived for each object from the optical by beagle (Table 2).

in the case of a CSFH or SSP alone. We either allow this quantity to vary over a uniform prior spanning the model age grid, or (as discussed below) assume a narrow Gaussian prior (σ = 0.1 dex.) fixed to the values derived for each object from the optical by beagle (Table 2). - 2.We also consider combinations of this base SFH with an additional SSP. This adds two parameters: the age of this second SSP

and its fractional contribution to the continuum at 1450 Å f+SSP.

and its fractional contribution to the continuum at 1450 Å f+SSP. - 3.The stellar metallicity,

. We always allow

. We always allow  to vary over a uniform prior from the minimum metallicity of the grid up to 0.5Z⊙, well above the metallicities preferred by these spectra.

to vary over a uniform prior from the minimum metallicity of the grid up to 0.5Z⊙, well above the metallicities preferred by these spectra. - 4.The multiplicative adjustment to the measured redshift fz , which we allow to vary by ±3%.

- 5.The linear offset in the model normalization δ y, which we allow to vary over (−0.1, 0.1).

- 6.The Gaussian smoothing kernel size σs . For the C&B models, we allow this to vary from 30 to 70 pixels, corresponding to 0.4–0.8 Å.

As usual, we are now interested in estimating the posterior distribution  the likelihood as a function of these model parameters given this model M and our data

D

.

the likelihood as a function of these model parameters given this model M and our data

D

.

To explore this parameter space and obtain constraints on the parameters of interest, we utilize dynesty (Speagle 2020). This code implements both static and dynamic nested sampling (Skilling 2004, 2006; Higson et al. 2019), which is a method for estimating simultaneously both the evidence P( D ∣M) and the posterior by integration in shells of constant likelihood. Though this method has more stringent requirements for prior specification than for instance Markov Chain Monte Carlo, this also forces it to fully explore the specified prior volume, making it far less likely to miss regions of high likelihood. We use the static nested sampler, adopting the default configuration of uniform sampling with multiellipsoidal decomposition bounding (Feroz et al. 2009). We extract confidence intervals on the key parameters of interest from the weighted sample distributions and draw samples from the posterior using the helper functions built into dynesty for precisely these functions (see also Hol et al. 2006).

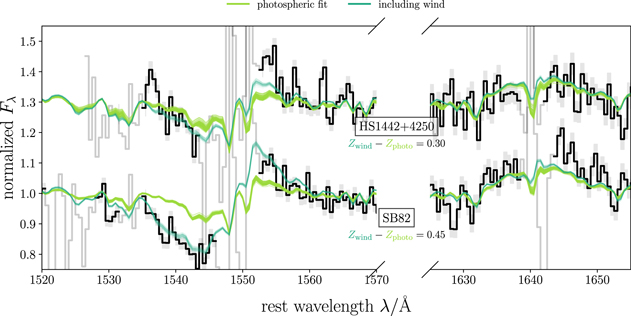

For illustration, we highlight the resulting posterior distribution in a corner plot presented in Figure 3 for J104457, whose FUV continuum SNR is typical for our sample. In general, the fit agreement to the photospheric continuum alone with wind lines masked is reasonable, with reduced χ2 of order unity and excellent morphological agreement with the highest-S/N spectra (Figure 4). Our photospheric fits with the C&B models uniformly support very small values for the multiplicative uncertainty factor fvar < 0.01, supporting the notion that our revised spectral uncertainties are not significantly underestimated. We discuss the fit results and their implied constraints on the stellar population properties of interest in the following section.

Figure 3. Corner plot for the dynesty fit to the full UV spectrum of J104457 (continuum S/N typical for our sample), with all wind features but C iv masked and assuming a variable-age CSFH and flat priors. All of the parameters including the “nuisance” quantities are reasonably well constrained, and in particular we find a single-peaked posterior distribution for the metallicity Z with minimal covariance.

Download figure:

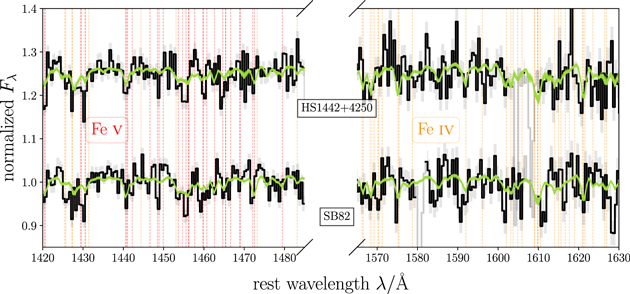

Standard image High-resolution imageFigure 4. Zoom-in on stellar continuum fits at the photospheric complex near 1450 Å for the two highest-S/N spectra in our sample: SB 82 and HS 1442+4250. The observed continuum-normalized data binned to model resolution is overlaid by C&B model spectra drawn from the posterior found by dynesty, for the full cleaned G160M spectrum without stellar wind lines included. Many blended iron absorption features are detected at model resolution and well reproduced by the C&B model spectra.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution image5. Results

The UV continuum fitting described in the previous section yields Bayesian constraints on the basic properties of the massive star populations in the context of the assumed stellar models. We now examine these fitting results (with important derived quantities compiled in Table 5) and consider them in the context of the other measurements of these systems.

Table 5. Stellar Metallicities Inferred from Fits to the FUV Continuum

| Target | Photospheric | CSFH, no age prior | 2 SSPs |

with stellar C iv with stellar C iv

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name |

(fiducial) (fiducial) |

|

|

|

|

|

| CSFH | 2 SSPs |

| J082555 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| SB2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| J104457 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| SB82 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| J120202 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| HS1442+4250 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Note. The fiducial stellar metallicity used in this paper is presented first, inferred from fits to the photospheric line-dominated normalized UV stellar continuum assuming a CSFH with age prior set by SED fitting. We also include stellar metallicities and ages inferred from fits with a flat prior to the same masked and normalized UV continuum assuming both a CSFH and a pair of SSPs with variable age below or above 5 Myr. Finally, we include metallicities derived given these two SFH assumptions when the broad stellar wind components of the C iv profile are fit directly alongside the photospheric lines.

Download table as: ASCIITypeset image

5.1. Metallicities from the Photospheric Continuum

5.1.1. Reproducing the Photospheric Lines

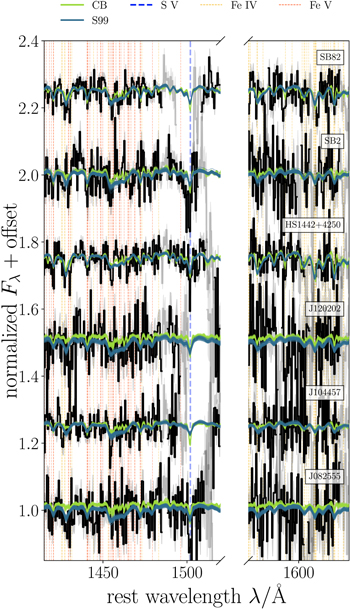

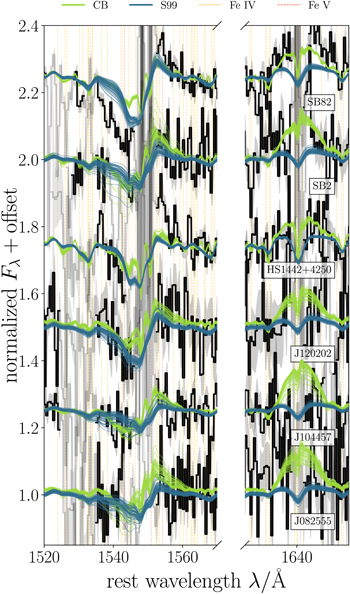

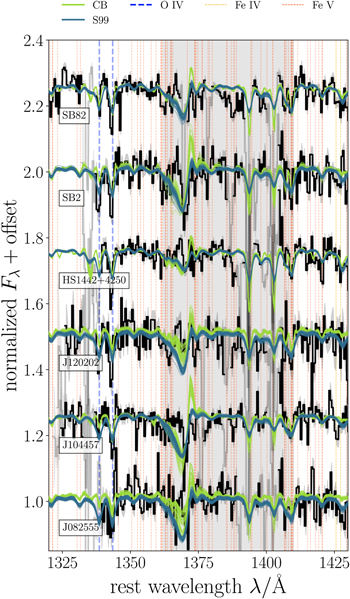

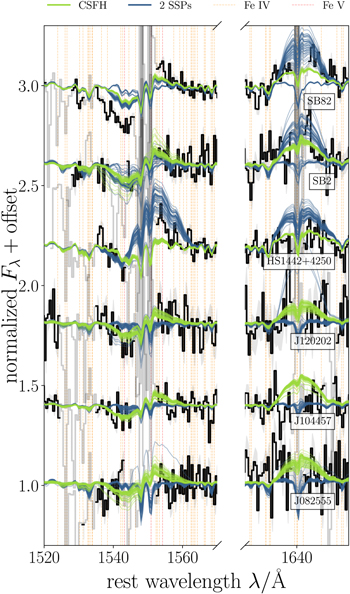

First, we examine how well the model spectra reproduce the forest of iron photospheric lines that provide direct leverage on the metallicity of the massive stars. In Figure 4 we compare model spectra drawn from the posterior distribution of the C&B fits against the observed binned spectra for the two highest-S/N spectra in our sample, SB 82 and HS 1442+4250, focusing on the regions 1420–1480 and 1570–1630 Å (the C&B and S99 fits for the other galaxies are included in Figure 10). These two regions of the spectrum of hot OB stars are expected to be dominated by a forest of Fe v and Fe iv lines (respectively), with minimal contamination from lines impacted by ISM absorption or stellar winds. By focusing on lines with minimal wind impact, we bypass much of the significant additional modeling uncertainties inherent to reproducing the structure of and radiative transfer through the expanding outer atmosphere of a wide variety of hot stars whose wide-ranging spectra must then be combined in the correct proportion (see Section 5.3). We indicate the expected vacuum wavelengths of the transitions predicted to be most prominent in hot stellar atmospheres for each of these iron species as reported by the Vienna Atomic Line Database (VALD3; Kurucz 2006; Ryabchikova et al. 2015, and references therein).

The comparison in Figure 4 reveals remarkably good agreement between the model and observed spectra in this region within the data uncertainties. In this wavelength range, a majority of the fluctuations in the observed binned continuum are due to real photospheric metal line absorption, detected cleanly at the resolution of the C&B SPS models. The fidelity with which the C&B model spectra are able to match most of the “wiggles” evident in the observed binned continuum in these systems attests both to the reality of these features in the data and to the precision of these model spectra. The lower-S/N spectra of the other targets (most notably J082555 and J120202) unsurprisingly reveal less striking agreement with the models (Figure 10). However, this is appropriately reflected in correspondingly large uncertainties in the derived metallicities.

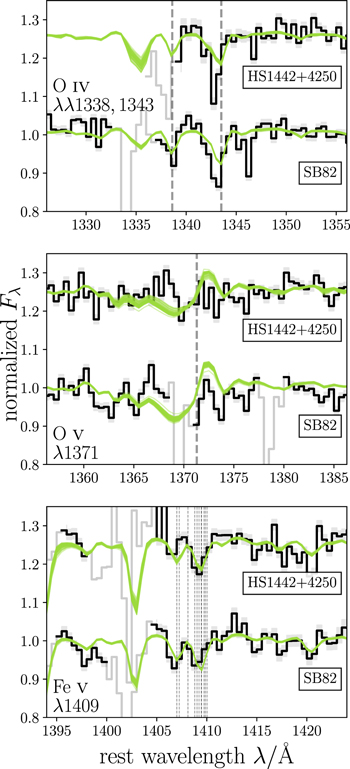

We note that the wavelength region spanned by our spectra also provide access to several other strong photospheric lines of non-iron peak species. Most prominent and least likely to be contaminated by ISM absorption among these in our systems are O iv λ λ1338, 1343, O v λ1371, and S v λ1502. We highlight the oxygen line complexes in comparison to a prominent blend of iron transitions for our two highest-S/N spectra in Figure 5 (the constraints on these lines for the other targets and the S99 fits are visible in Figures 10 and 12). Our fits are driven primarily by the far more numerous lines of iron in the continuum, and the model spectra (both C&B and S99) that best match this iron line forest appear to systematically underestimate the strength of these lines of oxygen and other excited α-elements. This comparison is complicated by the fact that stellar winds can contaminate several of these transitions especially O v λ1371 whose strong model mismatch we discuss further in Section 5.3, though we note that only a small velocity asymmetry as would be expected from a wind contribution is detected in O iv λ λ1338, 1343. Modulo the uncertain wind contribution, this systematic inability to match the strength of these photospheric lines of α elements is qualitatively consistent with an overabundance of these elements with respect to iron in the observed galaxies relative to the solar chemistry assumed by the models employed here. We discuss the consequences of this possibility further in Section 6.2.

Figure 5. Zoom-in on C&B stellar continuum fits at several key lines of oxygen for the two highest-S/N spectra (HS 1442+4250 and SB 82): O iv λ λ1338, 1343, O v λ1371, and for comparison the strong blend of iron transitions near 1409 Å. The models that are predominantly constrained to match the numerous lines of Fe in the continuum appear to systematically underestimate the strength of O iv in these systems, qualitatively consistent with an overabundance of these elements relative to a solar chemistry. The stellar wind-dominated model profile of O v is strongly inconsistent with the data, indicative of deficiencies in the treatment of massive star winds in the underlying model atmospheres (Section 5.3).

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution image5.1.2. Stellar Metallicity Constraints

The photospheric continuum fits provide Bayesian constraints on the stellar metallicity of these systems driven by the iron line forest. We present these constraints (medians and 68% confidence intervals) in Table 5 for several different sets of model assumptions. Here, we focus on the metallicity posterior derived assuming a constant star formation history with a Gaussian prior on age set by the ugriz SED fits to each system (Table 2, with Gaussian σ of 0.05 dex). We adopt this measurement as our fiducial metallicity for several reasons: it involves a minimal number of free parameters for the star formation history, and recovery of low metallicities near the edge of our metallicity prior is broadly successful even at S/N well below that reached by our sample with such an age prior (Appendix C.1). We note that minimal changes in the derived metallicity are observed when a conservative flat prior is adopted in age instead beyond a broadening of the posterior constraints, with the largest shift being a ∼ 1.9σ increase in Z for J104457 (Table 5). We discuss the other star formation history results in Section 5.3 and Appendix B.2, and the comparison with S99 in Appendix B.

The metallicities derived from the UV photospheric line fits are uniformly low. The UV spectra of these systems prefer metallicities below 10% solar ( ), with all but SB 2 confidently below this metallicity at > 1σ. This confirms that these systems are almost uniformly host to extremely metal-poor massive stars, despite the fact that two have Te

-derived oxygen abundances greater than the commonly adopted 10% solar cutoff at 12 + logO/H = 7.7 (Table 1). However, the results for our sample as a whole are also confidently not in the realm of nearly metal-free stars. All six have at least some photospheric metal line detection evident (Figure 10), and only the two lowest-metallicity and lowest-S/N spectra (J082555 and J120202) have posterior distributions approaching the bottom of our model metallicity range (and thus prior) at

), with all but SB 2 confidently below this metallicity at > 1σ. This confirms that these systems are almost uniformly host to extremely metal-poor massive stars, despite the fact that two have Te

-derived oxygen abundances greater than the commonly adopted 10% solar cutoff at 12 + logO/H = 7.7 (Table 1). However, the results for our sample as a whole are also confidently not in the realm of nearly metal-free stars. All six have at least some photospheric metal line detection evident (Figure 10), and only the two lowest-metallicity and lowest-S/N spectra (J082555 and J120202) have posterior distributions approaching the bottom of our model metallicity range (and thus prior) at  . The relatively confidently measured metallicities for the remaining four objects range from −3.2 to −2.9 in

. The relatively confidently measured metallicities for the remaining four objects range from −3.2 to −2.9 in  , corresponding to 4%–8% solar.

, corresponding to 4%–8% solar.

The highest photospheric metallicities we infer in our sample occur in SB 2 ( ), HS 1442+4250 (

), HS 1442+4250 ( ), and SB 82 (

), and SB 82 ( ). These systems reveal the clearest detections of photospheric absorption lines (Figures 4, 10), with inferred model “wiggles” notably more prominent than those in the three other systems. These systems also reveal the three highest abundances of gas-phase O/H, with the other three lower-O/H galaxies all constrained to confidently (at the 84% confidence level)

). These systems reveal the clearest detections of photospheric absorption lines (Figures 4, 10), with inferred model “wiggles” notably more prominent than those in the three other systems. These systems also reveal the three highest abundances of gas-phase O/H, with the other three lower-O/H galaxies all constrained to confidently (at the 84% confidence level)  (<6% solar). Further detailed comparison of these three lowest-metallicity systems is challenging due to both weak continuum features and low S/N in the spectra for J082555 and J120202. However, the apparent first-order correspondence between the gas and stellar abundances is less clear when the three higher-metallicity systems are examined more closely. In the gas phase, these three highest-Z systems vary in O/H by 0.27 dex, with HS 1442+4250 at 12 + logO/H = 7.66 ± 0.04 and SB 82 at 12 + logO/H = 7.93 ± 0.04. However, their stellar metallicities are far more tightly clustered over ∼0.1 dex, with HS 1442+4250 and SB 82 in particular highly inconsistent in gas-phase O/H but with fairly tightly overlapping stellar metallicity distributions. The similarity in their inferred stellar Z is consistent with the qualitatively similar strength of photospheric absorption in their spectra (Figure 4) and empirically measured absorption indices (Table 4).

(<6% solar). Further detailed comparison of these three lowest-metallicity systems is challenging due to both weak continuum features and low S/N in the spectra for J082555 and J120202. However, the apparent first-order correspondence between the gas and stellar abundances is less clear when the three higher-metallicity systems are examined more closely. In the gas phase, these three highest-Z systems vary in O/H by 0.27 dex, with HS 1442+4250 at 12 + logO/H = 7.66 ± 0.04 and SB 82 at 12 + logO/H = 7.93 ± 0.04. However, their stellar metallicities are far more tightly clustered over ∼0.1 dex, with HS 1442+4250 and SB 82 in particular highly inconsistent in gas-phase O/H but with fairly tightly overlapping stellar metallicity distributions. The similarity in their inferred stellar Z is consistent with the qualitatively similar strength of photospheric absorption in their spectra (Figure 4) and empirically measured absorption indices (Table 4).

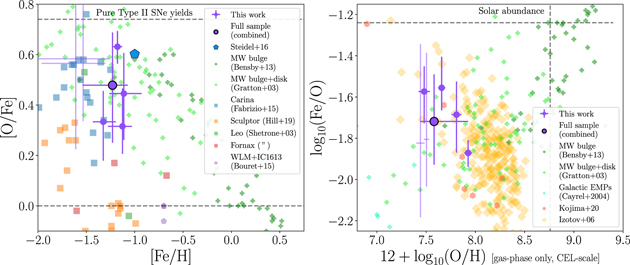

This analysis of the UV continuum features in these galaxies has revealed a crucial point: sorting these galaxies by gas-phase O/H yields a different rank ordering and a different spread than implied by the stellar photospheric lines. This immediately has important consequences for any work with local dwarf star-forming galaxies where only gas-phase abundances are known, which we discuss further in Section 6.1. It also strongly suggests that another variable is at play in setting the gas-phase oxygen and stellar iron abundances.

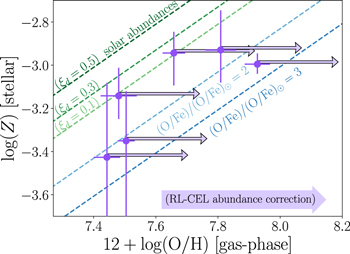

5.2. The O/Fe Abundance Ratio

Direct comparison of the iron-driven stellar photospheric metallicities and gas-phase oxygen measurements should yield an estimate of their relative abundance, and thereby insight into the α/Fe ratio in the star-forming ISM of these galaxies. Similar analyses conducted at z ∼ 2–4 have led to a strengthening consensus that super-solar O/Fe ratios are commonplace in star-forming galaxies at those redshifts (e.g., Steidel et al. 2016; Strom et al. 2018; Topping et al. 2020a), but the degree to which this applies to present-day bursting dwarf galaxies remains unclear. We plot our two abundance measurements in Figure 6, which immediately makes clear the lack of direct proportionality between these quantities as discussed in Section 5.1 and thus the possibility of a varying O/Fe ratio. However, comparing these abundances requires converting the ionized O/H measurement in hand to an estimate of total O/H commensurate with the stellar metallicity constraint. Correspondingly, Figure 6 also includes arrows representing gas-phase corrections and lines corresponding to solar abundance patterns with varying dust which we discuss in turn in this subsection.

Figure 6. Comparing the gas-phase oxygen abundances derived from the direct-Te method and stellar metallicity constraints found from the ultraviolet photospheric continuum fits for the galaxies in our sample. We overplot green dashed lines corresponding to an assumed solar abundance scale with varying dust depletion factors ξd according to Gutkin et al. (2016), and two blue dashed lines indicating the enhancement expected from an O/Fe overabundance relative to solar of 2 and 3 times (with ξd = 0.3). We also highlight with arrows the shift introduced to the gas-phase abundances when accounting for an offset between the recombination line and collisionally excited line abundance scales (see Section 5.2). Even without any abundance scale shift, the measured stellar metallicities lie systematically below those expected given the gas-phase oxygen abundances under the assumption of solar abundances.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageFirst, in order to place our oxygen abundances confidently on an absolute scale, we consider the abundance discrepancy problem associated with ionized nebulae (e.g., Tsamis et al. 2003). The vast majority of integrated galaxy studies rely on gas-phase oxygen abundances derived from the strong collisionally excited lines (CELs) of [O ii] and [O iii], as derived for our systems with the direct-Te

method in Section 2.1. However, far weaker optical recombination lines (RLs) of oxygen detected in bright nearby H iiregions enable an alternative measurement of O/H, which is found to be systematically larger by a fairly constant factor of order 2 than that derived from the collisionally excited lines (e.g., Peimbert et al. 1993; García-Rojas & Esteban 2007; Esteban et al. 2014). The origin of this offset and the correct metallicity scale remains unclear (see Maiolino & Mannucci 2019, for more detailed discussion and references), especially at low metallicity where recombination line measurements are scarce to nonexistent (see e.g., Bresolin et al. 2016, for an argument for smaller corrections at low metallicity). To test this in metal-poor dwarf galaxies, we have obtained deep echelle spectra in a complementary program which yield oxygen RL detections for two of the targets in this sample: SB 2 and 82, from which we obtain preliminary RL metallicities of  and

and  , respectively (R. L. Sanders et al. 2022, in preparation). These measurements are 0.22 and 0.38 dex higher than the direct-Te

measurements we derived for these systems in Table 1, consistent with previous H iiregion samples presented above. Motivated by these local findings and for consistency with similar analyses of gas and stellar abundances at z ∼ 2 (e.g., Steidel et al. 2016; Sanders et al. 2020), we adopt the recombination line scale. For simplicity, since we do not have RL measurements for the full sample, we apply a constant + 0.24 dex offset (factor of 1.7) to the direct-Te

O/H abundances from Table 1 for each galaxy.

15

, respectively (R. L. Sanders et al. 2022, in preparation). These measurements are 0.22 and 0.38 dex higher than the direct-Te

measurements we derived for these systems in Table 1, consistent with previous H iiregion samples presented above. Motivated by these local findings and for consistency with similar analyses of gas and stellar abundances at z ∼ 2 (e.g., Steidel et al. 2016; Sanders et al. 2020), we adopt the recombination line scale. For simplicity, since we do not have RL measurements for the full sample, we apply a constant + 0.24 dex offset (factor of 1.7) to the direct-Te

O/H abundances from Table 1 for each galaxy.

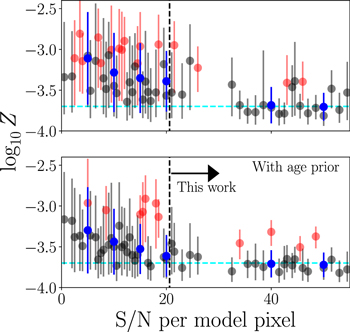

15