Abstract

Accretion disks around black holes power some of the most luminous objects in the universe. Disks that are misaligned to the black hole spin can become warped over time by Lense–Thirring precession. Recent work has shown that strongly warped disks can become unstable, causing the disk to break into discrete rings producing a more dynamic and variable accretion flow. In a companion paper, we present numerical simulations of this instability and the resulting dynamics. In this paper, we discuss the implications of this dynamics for accreting black hole systems, with particular focus on the variability of active galactic nuclei (AGN). We discuss the timescales on which variability might manifest, as well as the impact of the observer orientation with respect to the black hole spin axis. When the disk warp is unstable near the inner edge of the disk, we find quasi-periodic behavior of the inner disk, which may explain the recent quasi-periodic eruptions observed in, for example, the Seyfert 2 galaxy GSN 069 and in the galactic nucleus of RX J1301.9+2747. These eruptions are thought to be similar to the “heartbeat” modes observed in some X-ray binaries (e.g., GRS 1915+105 and IGR J17091-3624). When the instability manifests at larger radii in the disk, we find that the central accretion rate can vary on timescales that may be commensurate with, e.g., changing-look AGN. We therefore suggest that some of the variability properties of accreting black hole systems may be explained by the disk being significantly warped, leading to disk tearing.

1. Introduction

Accreting black holes come in different sizes, from stellar-mass black holes in X-ray binaries (e.g., Verbunt 1993; Remillard & McClintock 2006) to supermassive black holes in the centers of galaxies (e.g., Kormendy & Ho 2013). In all cases, the accreting matter is in the form of a disk (Pringle 1981). Disk formation is inevitable, as the matter possesses angular momentum that it cannot easily shed, whereas the excess energy associated with orbital eccentricity can be readily lost; collisions between gas orbits turn orbital energy into heat, which can be radiated away. Once in the form of a disk, additional energy may be extracted from the gas orbits. Disk viscosity, usually ascribed to turbulence in the disk (Shakura & Sunyaev 1973), leads to torques that transport angular momentum outward through the disk, allowing most of the matter to spiral slowly inward. This liberates gravitational potential energy. Accretion onto black holes extracts large amounts of energy per unit of mass accreted, and the high accretion rates that are sustainable onto supermassive black holes in galaxy centers makes them the most luminous continually emitting objects in the universe.

In simple accretion disks, e.g., those found in dwarf novae, the standard accretion disk model (Shakura & Sunyaev 1973) provides a good fit to the observed disk spectrum (e.g., Hamilton et al. 2007) and the thermal-viscous disk instability model provides a good description of the time dependence (e.g., Lasota 2001). However, even in similar types of system, e.g., the nova-like variables, the observed disk emission can deviate from the standard model and requires additional physical effects to be included (see, e.g., Nixon & Pringle 2019). In the dwarf novae and nova-like variables, the central accretor is a white dwarf. It should come as no surprise that accretion disks around black holes are more complex and often times provide more extreme behavior. In some cases, this is due to environmental effects, such as the surrounding matter responsible for creating broad emission lines in active galactic nucleus (AGN) spectra and producing the obscuring “torus” (Antonucci 1993; Ho 2008), or to additional physical processes such as relativistic jets and outflows that routinely accompany observations of high-luminosity black hole accretion at any mass scale (Russell & Fender 2010; Fabian 2012; King & Pounds 2015). These, and many other processes, imply that application of the standard disk model to the observed spectra of accreting black hole systems is often inadequate.

Recently, Lawrence (2018) highlighted a potentially more serious issue concerning the timescale of large-amplitude luminosity variations in AGN; see also Antonucci (2018) and references therein. What Lawrence points out (and Antonucci (2018) argues was already well-known; see, e.g., the discussion of Alloin et al. (1985)) is that the timescale on which a standard accretion disk is expected to vary—roughly the viscous timescale of the outer disk regions—is orders of magnitude larger than the observed variability timescales, and thus the standard disk model (comprising planar and circular orbits, with a local viscosity) is incompatible with the observed short-timescale, large-amplitude variability. Lawrence (2018) concludes that standard viscous disk theory be abandoned in favor of either (1) an extreme reprocessing scenario in which all the energy emerges from a quasi-point source and is reprocessed by a passive disk or external media, or (2) nonlocal processes capable of providing significantly shorter timescales via, e.g., large-scale magnetic stresses. The latter possibility is similar to the ideas put forth by King et al. (2004), but these have not yet been applied to AGN disk parameters; for more information, see also the discussion in Cannizzaro et al. (2020). The former scenario appears somewhat consistent with the standard disk model, in which the energy dissipation rate per unit of area is proportional to R−3, and thus the total energy released by the disk at each radius is proportional to 1/R. This, quite generally, arises as the gravitational potential scales as 1/R, and it is gravitational potential energy that is the source of the accretion luminosity. Thus, for example, in the standard model (and accounting for the zero torque inner boundary condition) ≈3/4 of the total energy emitted by the disk is emitted from radii between the inner most stable circular orbit, RISCO, and 10RISCO.

Reprocessing of this energy flux in the outer disk regions is then required to explain the large optical/UV fluxes observed in AGN, as a large emitting area is required. So, combining the large flux and large emitting area, it seems likely that large-scale reprocessing is necessary. 1 Such reprocessing of the central flux may occur most readily in the regions where the disk is strongly warped (see Natarajan & Pringle 1998), as the central regions then “see” a larger surface area of the disk. However, these arguments, which focus on the disk spectral properties, have little to say about the (in)appropriateness of the standard disk model for the dynamics of AGN disks. Instead, as noted by Lawrence (2018), it is the timescales on which the lightcurves vary that most cleanly provides information about the underlying dynamics—and thus is most useful in constraining disk models. What the energy arguments (and subsequent reprocessing) do tell us is that, if the central regions can vary (which is, of course, where the timescales are generally shortest), then we can expect the bulk emission properties to vary with it—and with lags between wave bands similar to those observed (De Rosa et al. 2015). A similar conclusion was reached by Sniegowska et al. (2020), who argue that the source of the variability lies in instabilities operating in the accretion disk (see also, e.g., Alloin et al. 1985). Recently, Ricci et al. (2020) showed that the changing-look AGN phenomenon can be associated with rapid evolution of the inner disk regions.

In this paper, we discuss the possibility that disk tearing (Nixon et al. 2012a), which occurs in warped accretion disks that achieve a warp amplitude sufficient to make them unstable to the disk-breaking instability (Doğan et al. 2018; Doğan & Nixon 2020), plays a role in producing variable accretion flows around black holes. For discussion of other possible mechanisms, we refer the reader to the discussion in Cannizzaro et al. (2020); see also Sniegowska et al. (2020). In Section 2, we provide an overview of the expected dynamics in unstable warped disks. In Section 3, we give the timescales on which the resulting variability can be expected to manifest. In Section 4, we explore the impact of the system orientation on the observable properties. In Section 5, we provide discussion, and we conclude in Section 6.

2. Dynamics of Disk Tearing

Warped disks have been found through direct and indirect methods in a variety of astrophysical systems. The most direct evidence now exists from spatially resolved observations of protoplanetary disks (e.g., Andrews 2020), and recent observations in this area have connected observed disk structures with disk tearing (Kraus et al. 2020). For disks around black holes, the most compelling evidence of disk warps comes from water masers (see Greenhill et al. (1995, 2003) and Miyoshi et al. (1995), and for further discussion, see also Maloney (1997)). Further evidence is derived from, for example, the long X-ray periods in X-ray binaries (e.g., the models of Wijers & Pringle (1999) and Ogilvie & Dubus (2001)) and quasi-periodic oscillations that are fit by the Relativistic Precession Model (RPM; Stella & Vietri 1998; Motta et al. 2014). As a specific example, warped disk models are used to explain the time-dependence of the X-ray flux in the X-ray binary Her X-1 (Scott et al. 2000; Leahy 2002). In the case of disks around black holes, when the disk is misaligned to the spin plane of a Kerr black hole, the disk orbits precess due to the Lense–Thirring effect. The rate of precession depends on the radius of the disk orbits from the black hole. Consequently, over time the disk acquires a differential twist and thus becomes warped.

The dynamics of a warped disk differ from that of a planar disk primarily due to a resonance between the orbital motion and the radial pressure gradient produced by the warped disk shape (Papaloizou & Pringle 1983), i.e., the midplanes, and thus the regions of high pressure, between two neighboring rings are misaligned; see, e.g., Figure 10 of Lodato & Pringle (2007). The radial pressure gradient, which oscillates around the orbit, induces epicyclic motion, which in a near-Keplerian disk also oscillates on the orbital timescale. The resonance leads to strong in-plane motions that communicate the disk warp radially and are damped by the disk turbulence. For the case of weak damping (referred to as “wavelike,” with α < H/R), the result is a propagating warp wave (Papaloizou & Lin 1995; Pringle 1999), while for the case of strong damping (referred to as “diffusive,” with α > H/R), the disk warp evolves following a diffusion equation (Pringle 1992; Ogilvie 1999). Here, we will consider the diffusive case, as black hole disks are typically expected to be thin and viscous. For a review of warped disk dynamics, see Nixon & King (2016).

Numerical simulations of warped disks have revealed that they can break into discrete rings that can subsequently precess effectively independently (see, e.g., Nixon et al. 2012a). 2 The simulation behavior, which sees rings of matter break off from the rest of the disk in regions where the warp amplitude 3 is high, hints at an underlying instability. Ogilvie (2000, Section 3) presents a stability analysis of the warped disk equations, finding that they can becomes viscously unstable. Doǧan et al. (2018) explore this instability in detail. They show that, for α ≲ 0.2, there is always a critical warp amplitude (that depends on the value of α) at which the disk becomes unstable, and further, they connect the instability with the disk-tearing behavior observed in the numerical simulations, arguing that it provides a physical mechanism underpinning the dynamical behavior. Doğan & Nixon (2020) further explore the properties of the instability for the case of non-Keplerian rotation that is relevant to disks around black holes. 4

The basic reason for instability is that, as warp amplitude increases, the internal stresses weaken, causing the disk to become less able to hold itself together (Ogilvie 1999; Nixon & King 2012). In a companion paper (Raj et al. 2021), we present numerical simulations of disks with various parameters, including the disk thickness, viscosity parameter, and inclination with respect to the black hole spin. We found that the properties of the simulated disks were consistent with, for example, the predictions for the critical warp amplitude at which the disk becomes unstable. We showed that disks with a lower viscosity parameter become unstable at lower warp amplitudes, and disks that are thinner and have a larger misalignment with respect to the black hole spin generally reach larger warp amplitudes and are thus more likely to become unstable. Once a disk becomes unstable, it breaks into two or more discrete rings, joined by a low-density transition region in which the orbital plane varies sharply with radius. As the warp is produced by the gravitational potential, which causes the orbits to precess, each of the individual rings subsequently precess with only weak interaction with neighboring rings. However, over time, the misalignment between neighboring rings grows and thus their velocity fields become partially opposed. Thus, any subsequent spreading of the rings—or perturbations to the orbits—results in collisions of the gas. This promotes shocks and the loss of rotational support for the gas. 5 This puts some of the gas on eccentric orbits (with apocenter at the radius of the original ring), which, upon reaching pericenter, have either accreted onto the central object or collide with other gas orbits to circularize at a smaller radius. As the precession timescale must be shorter than the standard viscous timescale in the disk in order to produce a substantial warp (Nixon et al. 2012a), this process enhances the accretion rate onto the central object by delivering matter to small radii faster than viscous torques could do so. The efficiency of this process is determined by the misalignment angle between the disk and the black hole. The maximum angle created between the disk orbits is twice the angle to the black hole spin vector. For small angles, the accretion rate may be enhanced by a factor of order unity, while for larger angles, the gas can fall a considerable distance in radius and increase the accretion rate substantially.

As two neighboring rings precess, their mutual misalignment angle oscillates between zero and twice their initial angle to the black hole spin vector. 6 Collisions between matter in the rings leads to shocks, as the orbital velocity is significantly larger than the sound speed for a disk. The resulting dynamics depends on the local cooling rate of the shocked gas. The relevant timescales are the expansion timescale ∼ H/cs (where the sound speed cs is that of the shocked gas) and the (typically free–free) cooling timescale (Pringle & Savonije 1979). If it can cool efficiently, then the cooling gas can fall inward to the new circularization radius (as above). However, if the cooling is inefficient, as might be expected in the innermost regions of the disk or if the shocks involve only a small amount of matter, the shocked gas takes on a more quasi-spherical distribution and can be supported somewhat against infall by pressure (see Stone et al. 1999). This shocked gas may resemble the X-ray corona (as suggested by Nixon & Salvesen (2014)), and its subsequent dynamics is yet to be explored fully but may resemble a radiatively inefficient accretion flow (see, e.g., Stone et al. 1999; Inayoshi et al. 2018).

An alternative possibility is that, in these central regions, the energy dissipated in the strong warping of the disk is not readily radiated away, and thus, on the timescales on which the viscous instability of the warp grows, the disk structure may be changed; specifically, the disk thickness may increase due to the additional dissipation of energy. This may have a stabilizing effect on the viscous instability, but may also lead to thermal instability and would also have a significant impact on the central accretion rate due to the dependence of the viscous timescale on disk temperature. We plan to explore this dynamics in subsequent work.

3. Timescales

In this section, we provide a discussion of the relevant timescales on which we can expect the disk to show variability. We limit the discussion to AGN disks. For discussion of the types of variability and the relevant timescales from disk warping and disk tearing in X-ray binaries, we refer the interested reader to Nixon & Salvesen (2014). Variability may also be produced by other mechanisms (e.g., Sniegowska et al. 2020), and the timescales may be affected by the inclusion of additional physics (e.g., Dexter & Begelman 2019). However, here we employ what we consider to be standard AGN disk structure, and we consider the effect of disk warping alone (for a broad discussion of several other mechanisms, we refer the reader to Section 4 of Cannizzaro et al. 2020).

AGN disks are expected to be limited in radial extent by their own self-gravity to a size on the order of Rsg = 0.02 pc, almost independent of disk or black hole parameters (Goodman 2003; King & Pringle 2007; Levin 2007). Disks that form or grow beyond this radius are typically gravitationally unstable, with Toomre Q = cs κ/π GΣ < 1 (Toomre 1964). This, coupled with rapid cooling rates compared to the local orbital period, results in fragmentation of the disk into stars at radii R > Rsg (Gammie 2001). This is consistent with the disk of stars observed in our own galaxy center, which orbit just outside this radius (Genzel et al. 2003; Ghez et al. 2005). For sufficiently large SMBH, with M ≳ 5 × 1010 M⊙, the self-gravity radius can be on the order of the gravitational radius of the black hole—and thus the formation of a stable accretion disk is likely to be prohibited (King 2016; see also Natarajan & Treister 2009). For black holes below this limit but with high mass, say M ≫ 108 M⊙, the disk extent is limited to 10–100 s of gravitational radii, and thus the entire disk may be in the regime where radiation pressure provides the dominant vertical support, i.e., determines the disk scale height. 7 For typical black hole masses of 106–108 M⊙, on the other hand, the self-gravity radius is large enough that radiation pressure there is not important.

The basic timescale on which an accretion disk evolves is the viscous timescale on which angular momentum is transported and matter diffuses through the disk, given by Pringle (1981)

where R is the disk radius and ν the kinematic viscosity. The viscosity in an accretion disk is usually modeled as ν = α cs H (Shakura & Sunyaev 1973), and is assumed to originate from hydromagnetic turbulence; for further discussion, see, e.g., Martin et al. (2019). In black hole accretion disks outside of quiescence, the accretion rate is typically high enough that the disk is sufficiently ionized for the magnetorotational instability to provide a source of disk turbulence (Balbus & Hawley 1991). Application of the disk structure presented by Collin-Souffrin & Dumont (1990), for the case where radiation pressure is not important, yields (King & Pringle 2007)

where is the radiative efficiency of accretion and LEdd is the Eddington luminosity. Thus, the timescale of variability associated with the accretion timescale of the disk itself is long, and commensurate with the timescales on which AGN global properties appear to “flicker” (King & Nixon 2015; Schawinski et al. 2015). However, this timescale is not consistent with short-timescale, large-amplitude variability observed in AGN lightcurves (as has been pointed out by, for example, Lawrence (2018)). If this short-timescale variability arises due to viscous inflow of matter, i.e., the luminosity variations are produced by the standard energy dissipation in an accretion disk due to viscous torques, then some mechanism is required for creating time-dependent fluctuations in the mass flow rate at smaller radii.

For smaller radii, we need to account for the effects of radiation pressure on the disk vertical structure (Novikov & Thorne 1973; Shakura & Sunyaev 1973). In this case, the viscous timescale can be written as (e.g., Dexter & Begelman 2019)

where  is the accretion rate in Eddington units and we have assumed electron scattering opacity. From this, we can see that if mass can be fed in a time-dependent manner to radii of order 10–50Rg, then the corresponding viscous timescales (of weeks to years) are capable of providing the necessary timescales to generate the observed luminosity variations.

is the accretion rate in Eddington units and we have assumed electron scattering opacity. From this, we can see that if mass can be fed in a time-dependent manner to radii of order 10–50Rg, then the corresponding viscous timescales (of weeks to years) are capable of providing the necessary timescales to generate the observed luminosity variations.

For the disk-tearing scenario described in Section 2 above, the other basic timescale is the time taken for disk orbits that are misaligned to the black hole spin to precess around the black hole spin vector—the nodal (or Lense–Thirring) precession timescale. For a test particle orbiting the black hole, this is given by 8

where Ωnp is the (nodal) precession frequency, R is the disk radius, Jh is the black hole angular momentum, a the black hole spin, and Rg = GM/c2 the gravitational radius of the black hole.

Equation (4) gives the timescale on which a single narrow ring of gas orbiting a black hole undergoes nodal precession. However, in general, precessing rings of gas are accompanied by other precessing rings or a warped and precessing outer disk. For two freely precessing rings separated by a radial distance of ΔR, the differential precession timescale on which the rings precess apart is given by

where in the last step we have assumed that ΔR ≪ R. 9 For rings produced by disk tearing, we expect ΔR ≳ H when the disk is strongly unstable and can have ΔR ≫ H when it is only weakly unstable.

As discussed above, the disk dynamics resulting from the instability of the disk warp can produce different scenarios. If the innermost regions of the disk are unstable, then we expect the variability to manifest on the precession timescale of the inner disk regions. In particular, in this case, we expect variability on the differential precession timescale (5), and the disk matter may plunge directly into the hole. If, instead, the disk is unstable further out such that the mass flow from the unstable region does not reach the ISCO, then the matter circularizes at a new smaller radius. 10 In this case, there are several competing timescales for the variability. The (differential) precession timescale determines the timescale for shocks between rings and the inflow of matter. The orbits circularize at their new smaller radius efficiently on the local orbital time (due to additional shocks at smaller radii; see Nixon et al. (2012b)). Then, once the material is circularized, a strong increase in disk luminosity follows over a timescale on the order of the viscous timescale (3) from the new radius. It is worth noting that, for a ring of material placed at some radius around a central accretor, the luminosity rises rapidly to a peak and then declines at a slower rate (e.g., Figure 3 of Nixon & Pringle 2021), which is consistent with the shapes of the lightcurves of some variable AGN (e.g., as noted for J0225+0030 by MacLeod et al. (2016)). An additional source of variability may arise from the changing geometry of the system with respect to the line of sight, which we discuss further in Section 4.

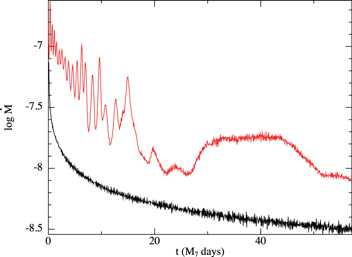

In Figure 1, we provide some example accretion rate curves from the simulations presented in Raj et al. (2021). In this figure, the accretion rate is plotted on a log scale and in arbitrary units. The time axis has been scaled to days for a 107 M⊙ black hole, which can be rescaled to any mass black hole by multiplying the time axis by M/107 M⊙. The black line corresponds to the accretion rate in the simulation with α = 0.03, H/R = 0.02, and θ = 10°, where θ is the initial angle between the disk and black hole spin. The red line corresponds to the accretion rate for the same parameters, except for this time θ = 60°. For the 10° case, the disk attains a mild warp, which does not create a noticeable impact, and thus the accretion rate closely resembles the accretion for a planar disk. In the figure, we see the accretion rate slowly decline with time as the simulated disk loses mass through the inner boundary at RISCO and spreads to larger radii. In contrast, for the 60° case, the disk undergoes disk tearing in the inner regions at early times (the first ≈10 days of evolution), and over time the unstable region moves outward over time. After t ≈ 10 days, precessing rings at larger radii (10 s of Rg) feed matter into an aligned disk at radii between RISCO and a few RISCO. Thus, the variability in the accretion rate becomes both longer-timescale and lower-amplitude as the innermost aligned disk’s viscous timescale regulates the accretion. This shows that short-timescale (weeks to months) and large-amplitude (factors of several) variability in the accretion rate on to supermassive black holes could be caused by disk tearing. We expect that this variability would be reflected in the time-dependent emission of such systems, as the accretion rate is a reasonable proxy for the rate at which energy can be extracted from the disk orbits.

Figure 1. Example accretion rates vs. time from the simulations presented in Raj et al. (2021). The two curves represent the accretion rate in the simulations with α = 0.03, H/R = 0.02, θ = 10° (black line), and θ = 60° (red line). The accretion rate is plotted on a log scale and is in arbitrary units. The time axis has been scaled to days for a 107 M⊙ black hole, which can be rescaled to any mass by multiplying the time axis by M/107 M⊙. The 10° simulation achieves a mild warp, which does not strongly impact the disk structure, and thus the accretion rate is similar to a planar disk, with the slow decline caused by the disk accretion and spreading to larger radii with time (the simulations did not model a steady disk with mass input over time). The 60° simulation achieves a strong warp, which does result in disk tearing. At early times, the inner disk is unstable, resulting in periodic accretion of rings of matter. At later times, the unstable region moves to larger radii and the inner disk is aligned to the black hole spin. This results in lower-amplitude and longer-timescale variability. Note that the properties of the disk tearing events, e.g., the radius and thus timescale at which they occur, depends on the disk properties and also the black hole spin. Therefore, this plot should be taken as representative of the kind of behavior that may occur, but not a prediction of an accretion rate for any particular system.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution image4. Impact of System Orientation

In the previous section, we discussed the timescales on which the disk structure is expected to vary, through either accretion (Equation (1)) or precession (Equations (4) and (5)). In this section, we discuss the impact of the orientation of the system with respect to an observer.

In general, the angle between the black hole spin and the accretion disk angular momentum is expected to decrease over time through dissipation between neighboring rings 11 ; Lense–Thirring precession of each ring maintains the inclination angle with respect to the black hole, and subsequent interaction between neighboring rings that occupy different planes (e.g., ones that have precessed apart) reduces the inclination to the black hole spin. This means that a line of sight that is closer to the black hole spin axis than the original disk misalignment always has a clear view of the disk center. In this case, any observed variability is caused by either emission from the shocks occurring between precessing rings in unstable regions of the disk or from the variable accretion rate caused by the time-dependent mass flow rates from the unstable regions.

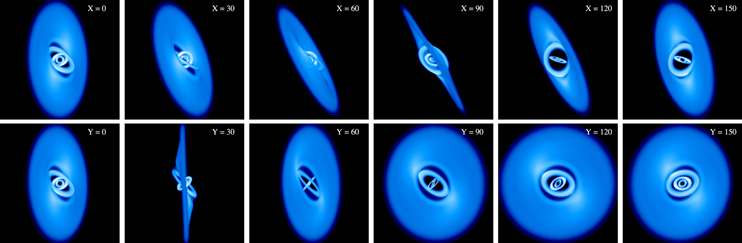

However, if the line of sight to the black hole passes through the disk (i.e., θobs > θdisk) then additional variability due to obscuration effects is possible. If the disk warp (i.e., the outer disk regions that do not undergo disk tearing) move into (or out of) the line of sight, then the emission properties vary significantly as the inner regions of the disk are blocked (revealed), and the timescales for such changes are long—relying upon precession at large radii (see Equation (4)) or slow decay of the disk warp. However, if the interloper is instead a ring of matter in the unstable region of the disk, then we can expect the precession timescale at that radius to be imprinted on the emission, as the ring blocks some of the flux from the central regions reaching the observer. The presence of multiple such rings with different inclinations blocking different parts of the disk at different times may erase a simple periodic signal, but the generic timescale for variability from a ring at a given radius is governed by Equation (4). In Figure 2, we show an example of the effect different orientations may have on the system properties. Each panel in the figure is the same disk model (α = 0.03, H/R = 0.02 and θ = 60°) viewed at the same time but from a different orientation. The black hole spin axis is in the z-direction and the reference views are of the x–y plane (the top and bottom leftmost panels, which are the same), and thus the black hole spin points out of the page in the leftmost panels. The top row of panels, from left to right, are views of the disk, starting with the x–y plane, that are subsequently rotated by an angle X around the x-axis. The bottom panels are the same, but now the rotation is performed by an angle Y around the y-axis. The central regions are clearly visible in some configurations, whereas in others they are largely blocked from view—either by the outer disk or a precessing ring that is crossing the line of sight to the disk center.

Figure 2. Three-dimensional renderings of the gas distribution in a disk-tearing simulation with α = 0.03, H/R = 0.02, and θ = 60° (Raj et al. 2021). Each panel depicts the same simulation at the same time, viewed from different orientation. Left-hand top and bottom row panels both show the same view—that of the x–y plane—where the black hole spin axis, which coincides with the z-axis, points out of the page. From left to right, the top row shows the disk view with the disk rotated by an angle X around the x-axis, where the value of X in each case is given in the panel. In contrast, the bottom row is rotated from the x–y plane by an angle Y around the y-axis. In some cases, the majority of the disk is visible and pointed predominantly toward the “observer,” while in other cases, the inner disk regions are highly inclined or obscured by either the warped outer disk or an interloping ring of matter in the unstable region.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageFinally, we note that, while the geometry may be important for determining which parts of the disk are seen by the observer, it is also important for determining which parts of the disk are available to be seen by the material that makes up the broad line region (typically assumed to be clouds orbiting near the outer disk regions). As the matter comprising the broad line region is typically expected to orbit close to the original disk plane, it is plausible that precessing rings in the unstable region of the disk may act to block the central disk emission from fully illuminating the broad line regions. Thus, an observer looking unobstructed at the disk central regions may see a constant flux, but the flux arriving at the broad line regions may be time-variable. This could cause a disconnect between the continuum and emission lines, and may thus offer a potential cause for the recently observed “broad line holidays” (Goad et al. 2016, 2019).

5. Discussion

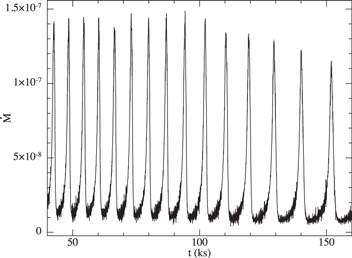

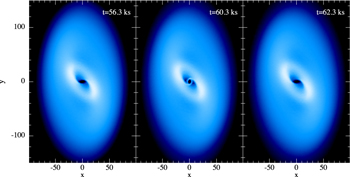

In the previous sections, we have discussed the dynamics of disk tearing, the timescales on which variability might manifest in the observable properties, and how the disk geometry can affect what we see. Here, we discuss the possible connection between disk tearing and rapid flaring variability observed in some AGN (referred to as quasi-periodic eruptions), which may also be related to the “heartbeat” modes of some X-ray binaries. In the left-hand panel of Figure 3, we provide the accretion rate with time of the simulation reported in Raj et al. (2021) with parameters α = 0.03, H/R = 0.05, and θ = 60°, performed with 106 particles. In this simulation, the disk-tearing behavior was restricted to the innermost regions of the disk (Figure 4). The disk inner edge warps with time, and then, once the warp amplitude is large enough, the innermost ring (with radial thickness ΔR ∼ H) breaks off and begins to precess. Once a large angle is reached with the next ring of the disk, shocks occur and the innermost ring is robbed of rotational support and accretes dynamically onto the black hole. This process repeats, and thus quasi-periodicity is imprinted on the accretion rate shown in Figure 3. We anticipate that this signal is imprinted on the observable properties of the system, primarily through radiating away the energy generated by the shocks between the innermost rings. Thus, we expect the high-energy flux (e.g., X-rays) to broadly follow the same time-dependence as the accretion rate in the simulation.

Figure 3. Accretion rate onto the black hole in the simulation presented by Raj et al. (2021) with α = 0.03, H/R = 0.05, and θ = 60° with the disk modeled with 106 particles. Time axis has been scaled such that the units are kiloseconds for a 4 × 105 M⊙ black hole. We note that the timescale on which the behavior occurs depends on where in the disk the instability occurs. Here, it occurs at the inner disk edge (see Figure 4), but this can be scaled to longer timescales if the behavior occurs at larger radii (see Equation (4)). The accretion rate is in arbitrary units. In this case, the disk-tearing behavior is restricted to the disk inner regions (see Figure 4). The inner disk behavior is cyclic: the innermost ring of matter is torn off, then precesses until it interacts strongly with the neighboring ring and is robbed of angular momentum, loses rotational support, and accretes dynamically on to the black hole. The accretion rate is representative of the dissipation rate in the inner disk regions, and therefore may reflect the rate of generation of energy from the accretion flow. This should be compared to Figure 1 of Miniutti et al. (2019) for GSN 069; Figure 1 of Giustini et al. (2020) for RX J1301.9+2747; or for the “heartbeat” mode in X-ray binaries, to (for example) Figure 1 of Zoghbi et al. (2016) for GRS 1915+105.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageFigure 4. Disk structures from the simulation accretion rate depicted in Figure 3 at three times just before, during, and after a peak in the accretion rate. Axes are in units of gravitational radii (Rg = GM/c2). Color denotes the column density, with white being the highest and dark blue the lowest. Times in the plots have been scaled to represent a 4 × 105 M⊙ black hole (same as Figure 3). Left-hand panel shows the disk in a warped state. Middle panel shows the innermost ring broken off from the disk. Right-hand panel shows a return to the warped state once the ring has been accreted.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageRecently, Miniutti et al. (2019) have reported quasi-periodic eruptions in XMM-Newton and Chandra observations of the Seyfert 2 galaxy GSN 069. The eruptions occur approximately every nine hours and are seen in observations spanning several months. The 0.4–2 keV flux increases by a factor of order 10–100 for a duration of approximately one hour. Comparison of these eruptions with the accretion rate shown in Figure 3, perhaps also with an additional X-ray emitting component to provide a base-level of flux (e.g., the disk corona), are again suggestive. Applying the black hole mass of 4 × 105 M⊙ to the simulation data results in a recurrence period of ∼3.5 hr. 12 Similar behavior has also been reported for the galactic nucleus of RX J1301.9+2747 (Giustini et al. 2020). Here, the black hole mass is reported to be 0.8–2.8 × 106 M⊙, and with the eruptions separated by ∼20 ks, these eruptions are also consistent with the timescale shown in Figure 3, with variations in the disk structure shown in Figure 4. We therefore suggest that these quasi-periodic eruptions may be the result of the disk inner regions undergoing disk tearing, with the resulting shocks that occur when broken-off rings collide providing the additional energy dissipation to power the eruptions. This behavior may appear as if the inner disk temperature briefly rises due to the additional dissipation of energy. If the black hole mass in GSN 069 is on the order of 4 × 106 M⊙, then the nine-hour eruptions are consistent with the free precession timescale (Equation (4)) at R ≈ 25Rg, but due to the precession of neighboring material (Equation (5)), the location is more likely to be at or close to the disk inner edge ≲ a few × RISCO. It is also interesting to note that the eruptions do not seem to have been present while the source was at higher luminosity (see, e.g., Shu et al. 2018). This may indicate that, as suggested by the simulations of Raj et al. (2021), variations in disk parameters (in this case, the disk thickness, which is expected to be higher for higher Eddington ratio) are responsible for generating changes in the variability of the accretion flow. For the disk-tearing scenario discussed here, the disk parameters are responsible for determining the location and strength of the instability—and thus the timescale and amplitude of the variability.

As noted by Miniutti et al. (2019), the time dependence is reminiscent of the “heartbeat” mode of some X-ray binaries, e.g., GRS 1915+105 and IGR J17091-3624 (Belloni et al. 1997; Altamirano et al. 2011), and recently reported in an X-ray source in the galaxy NGC 3621 (Motta et al. 2020). In these systems, the timescales on which the beats recur is 10–100 s. Scaling the simulation data to a black hole of mass 10M⊙, the recurrence time is ∼0.3 s. In the simulation, we take the black hole spin to be a ≈ 0.5, and while a higher spin value might reduce some timescales (by moving the ISCO closer to the black hole horizon), it may also move the location of the tearing region (where the warp amplitude is highest) outward and thus increase the precession timescale on which the periodic behavior occurs. Similarly, different values of α or H/R would affect the location of the instability in the disk—and thus the type and properties of the subsequent variability. An additional possibility in these disks is that the location of the thin, i.e., radiatively efficient, disk inner edge is truncated at a radius larger than that of the ISCO, with a radiatively inefficient flow inside. If disk tearing occurs at the inner edge of the thin component of the disk, then the truncation radius determines the fastest precession timescales. Increasing the radius of warping instability by a factor of 4–5 would bring the timescales into agreement for, e.g., GRS 1915+105.

6. Conclusions

We have discussed the dynamics of disk tearing, which Nixon et al. (2012a) suggest may provide a source of variability in black hole accretion, and Nixon & Salvesen (2014) discuss in the context of X-ray binaries. Disk tearing is caused by an instability of the disk warp, and occurs most prominently when the disk viscosity is weak (α ≲ 0.1) and the warp amplitude is large (Ogilvie 2000; Doğan et al. 2018; Doğan & Nixon 2020). In a companion paper, Raj et al. (2021), we present the results of numerical simulations of disk tearing around black holes. Here, we have discussed the resulting dynamics and the timescales on which we expect black hole disks to show variability. We have suggested that the large-amplitude, short-timescale variability exhibited by AGN may be explained by the disk undergoing such dynamics, and that this can result in intrinsic changes to the disk (both geometric and energy dissipation/accretion rate changes) and also, in some cases, to changes to the observable properties of the disk through time-dependent obscuration. These effects may account for the short-timescale evolution observed in, for example, changing-look AGN. We have also shown that, for some disk parameters, disk tearing can occur predominantly at the disk inner edge, and that these cases show similarity with the quasi-periodic eruptions observed in GSN 069 and RX J1031.9+2747 and the “heartbeat” mode observed in some X-ray binaries. In future work, we will develop more sophisticated simulation models to connect in more detail with the available observational data.

We thank the referee for a helpful report. We thank Jim Pringle for useful comments on the manuscript. We thank Mike Goad for useful discussions on the observed properties of AGN. C. J. N. is supported by the Science and Technology Facilities Council (grant number ST/M005917/1). C. J. N. acknowledges funding from the European Unions Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No 823823 (Dustbusters RISE project). This research used the ALICE High Performance Computing Facility at the University of Leicester. This work was performed using the DiRAC Data Intensive service at Leicester, operated by the University of Leicester IT Services, which forms part of the STFC DiRAC HPC Facility (www.dirac.ac.uk). The equipment was funded by BEIS capital funding via STFC capital grants ST/K000373/1 and ST/R002363/1 and STFC DiRAC Operations grant ST/R001014/1. DiRAC is part of the National e-Infrastructure. We used splash (Price 2007) for the figures.

Footnotes

- 1

Heating of the outer disk is also a required addition to the standard disk model in its application to the lightcurves of soft X-ray transients (SXTs), where the outbursts exhibit long exponential decay (King & Ritter 1998). In all X-ray binaries, it is well-known that reprocessing of inner disk emission is required to explain the optical to X-ray flux ratios (van Paradijs & McClintock 1994). In AGN, the peak temperature of a standard accretion disk typically corresponds to rest-frame wavelengths in the extreme ultra-violet, which, if it is to be seen (at low redshift), typically has to be reprocessed into the optical/UV. It is worth noting that an irradiated disk is expected to have T(R) ∝ R−1/2, in contrast to the typical T(R) ∝ R−3/4, and by modeling the broadband spectra of 23 Seyfert 1 galaxies, Cheng et al. (2019) find that the temperature profiles are best fit with power-law indices ranging from −1/2 to −3/4. The suggestion that irradiation and reprocessing of central emission plays an important role is not new (see, e.g., Collin-Souffrin 1991).

- 2

Nixon et al. (2012a) used Lagrangian (SPH) hydrodynamics (see also Larwood et al. 1996; Larwood & Papaloizou 1997; Nixon et al. 2013; Doğan et al. 2015; Kraus et al. 2020; Raj et al. 2021). This behavior has also been found in numerical simulations employing Eulerian (grid) hydrodynamics (e.g., Fragner & Nelson 2010), and in simulations that model the effects of magnetic fields (Liska et al. 2021).

- 3

The warp amplitude,

, where

ℓ

is the unit of angular momentum vector pointing normal to the orbital plane at radius R, is a dimensionless measure of the strength of the disk warp.

, where

ℓ

is the unit of angular momentum vector pointing normal to the orbital plane at radius R, is a dimensionless measure of the strength of the disk warp. - 4

It is worth noting that essentially all of the analytical work on the dynamics of warped disks makes use of a Navier–Stokes (local and isotropic) viscosity (but see, e.g., Appendix C of Nixon 2015). The numerical work generally makes the same assumption by applying a Navier–Stokes viscosity to model the physical viscosity in a disk (but see, e.g., Liska et al. 2021). Pringle (1992) notes that this may not be right in real disks, where the angular momentum transport and dissipation arises through a combination of turbulent and magnetic processes. It has been shown by Torkelsson et al. (2000) (see also Ogilvie 2003) that hydromagnetic turbulence produced by the magnetorotational instability (MRI) leads to the dissipation of motions induced by a warp at a rate that is consistent with an isotropic viscosity. Similarly, Zhuravlev et al. (2014) note that, while the viscosity they measure from their GRMHD simulations is anisotropic, they find that “the effects of anisotropic viscosity on the evolution (of the disk structure) may be rather small.” Nealon et al. (2016) establish that the results of numerical simulations that employ a Navier–Stokes viscosity provide results that are indistinguishable from simulations that model MRI-driven turbulence explicitly. So, to the extent that numerical magnetohydrodynamics is capable of modeling the angular momentum transport and energy dissipation in real disks, we can expect the disk models based upon a Navier–Stokes viscosity to provide a reasonable description of the disk dynamics. King et al. (2007) and Martin et al. (2019) have argued (see also the discussion in Pjanka & Stone 2020) that current MHD models are inadequate for explaining the observed behavior in accreting systems, particularly with respect to the magnitude of the angular momentum transport and the nature of the energy dissipation, with the latter in numerical MHD models typically controlled by numerical dissipation. Thus, our understanding of accretion disk dynamics is not yet so well-established that we can be sure that the disk-tearing behavior seen in numerical simulations (now found with both Lagrangian and Eulerian methods, and with viscosity modeled as either Navier–Stokes or explicit MHD turbulence) can occur in real disks. However, all that is physically needed for the disk to be unstable in this manner is that, as the disk warp grows, the disk becomes less and less able to hold itself together. More explicitly, the internal torque attempting to keep the disk locally flat must decrease sufficiently with increasing warp amplitude. This seems reasonable to expect from a physical disk, and this has potentially been seen in the protostellar system GW Ori (Kraus et al. 2020).

- 5

It may appear that angular momentum is not conserved, as the gas has experienced a reduction in angular momentum. However, the total angular momentum, including the angular momentum transferred to the black hole through the back reaction of the Lense–Thirring effect, is conserved through this process. Essentially, the disk orbits have borrowed angular momentum from the hole in order to change their orbital plane and thus allow internal cancellations within the disk.

- 6

The maximum angle is somewhat reduced by the rings also slowly aligning with the black hole spin vector, and in general, simulations show that the inner ring is closer to alignment than the outer ring. Thus, when the disk is close to the line of stability, i.e., the warp amplitude is not far from the critical value for instability and the growth rates of the instability are small, the internal angle is much less than the maximal value. However, for regions of strong instability and growth rates on the order of the dynamical timescale, the angle is close to the maximal one.

- 7

- 8

Note that, close to the black hole, this formula is strictly only valid for small black hole spin. For example, for a ≈ 0.5, this formula underpredicts (compared to the full Kerr solution) the precession timescale by roughly 20 % near the ISCO. Accurate formulae for the frequencies are required for, e.g., the Relativistic Precession Model (RPM) of Stella & Vietri (1998), and are provided by, e.g., Motta et al. (2014). The RPM requires disk matter to perform orbits that are close to test particle orbits and have nonzero misalignment and eccentricity near the ISCO. The latter requirement, coupled with the success of the RPM in fitting QPOs in X-ray binaries, provides motivation for warped disks to exist at small radii around black holes (and the eccentricity may be provided by interacting rings and the partial exchange of orbital angular momentum between them). On the other hand, the former requirement, i.e., that the orbits behave individually rather than as a collective fluid, requires—as noted by Doğan & Nixon (2020)—that the disk be unstable to breaking up into discrete parts, which could be a result of disk tearing.

- 9

We note that, if ΔR ∼ R, then this patch of the disk no longer follows the precession timescale of a particular disk location, but instead follows the angular momentum weighted average precession timescale (e.g., Larwood & Papaloizou 1997).

- 10

Typically, the new orbits here are close to alignment with the black hole spin, as the reduction in angular momentum of the material comes from the misaligned component of the original orbits. However, a small residual misalignment is possible and the orbits are initially eccentric. Note that the system as a whole conserves angular momentum, but each ring of gas in the disk borrows angular momentum from the black hole via the Lense–Thirring effect in order to be misaligned to neighboring rings. Subsequent interaction between the misaligned rings can reduce the orbital angular momentum of both (see Equation (5) of Hall et al. 2014).

- 11

However, there are exceptions to this. For example, if one includes the effects of radiation warping, it is possible for the disk to achieve a shape in which the entire sky—as seen from the black hole—is covered by the disk surface (Pringle 1997). Alternatively, if the total disk angular momentum dominates the angular momentum of the black hole and the disk is initially closer to counteralignment (i.e., the disk–black hole angle is θ > 90°), then while the inner disk regions initially counteralign (θ → 180°) with the black hole spin, the outer regions (on a longer timescale) align (θ → 0°) with the black hole spin (King et al. 2005; Lodato & Pringle 2006) and thus any line of sight may become blocked over time.

- 12

We note that no attempt has been made to survey different disk–black hole parameters in order to achieve a better fit. Such an effort would not currently be useful, as the black hole mass is not constrained to high enough precision. Miniutti et al. (2019) estimate the uncertainty at the factor of a few level. They further estimate the black hole mass from the fundamental plane of black hole accretion (Shu et al. 2018) and find a value of 2 × 106 M⊙, in which case the simulated period would be ∼17.5 hr.