Abstract

We investigate the redshift evolution of intrinsic alignments (IAs) of the shapes of galaxies and subhalos with the large-scale structures of the Universe using the cosmological hydrodynamic simulation, Horizon Run 5. To this end, early-type galaxies are selected from the simulated galaxy catalogs based on stellar mass and kinematic morphology. The shapes of galaxies and subhalos are computed using the reduced inertia tensor derived from mass-weighted particle positions. We find that the misalignment between galaxies and their corresponding dark matter subhalos decreases over time. We further analyze the two-point correlation between galaxy or subhalo shapes and the large-scale density field traced by their spatial distribution, and quantify the amplitude using the nonlinear alignment model across a wide redshift range from z = 0.625 to z = 2.5. We find that the IA amplitude, ANLA, of galaxies remains largely constant with redshift, whereas that of dark matter subhalos exhibits moderate redshift evolution, with a power-law slope that deviates from zero at a significance level exceeding 3σ. Additionally, ANLA is found to depend on both the stellar mass and kinematic morphology of galaxies. Notably, our results are broadly consistent with existing observational constraints. Our findings are in good agreement with previous results of other cosmological simulations.

Original content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 licence. Any further distribution of this work must maintain attribution to the author(s) and the title of the work, journal citation and DOI.

1. Introduction

The shape and spin of galaxies are not randomly oriented but exhibit preferential alignments with the surrounding large-scale structure in the Universe. This intrinsic alignment (IA) of galaxies has come to be considered closely linked to galaxy formation processes and the underlying matter distribution in the Universe (for reviews, see B. Joachimi et al. 2015; A. Kiessling et al. 2015; D. Kirk et al. 2015; M. A. Troxel & M. Ishak 2015). An early theoretical investigation was presented in C. Pichon & F. Bernardeau (1999); they showed that the kinematics of the large-scale flow would impact IAs on scales of a few h−1 Mpc and below.

On the other hand, the IA of galaxy shapes is a major source of systematic bias in weak gravitational lensing measurements as it produces an effect that closely resembles cosmic shear (R. A. C. Croft & C. A. Metzler 2000; P. Catelan et al. 2001; D. Aubert et al. 2004; C. M. Hirata & U. Seljak 2004). Hence, it significantly contaminates the measure of cosmological parameters, complicating the interpretations of weak lensing results. Upcoming surveys, such as Euclid (Euclid Collaboration et al. 2025), the Vera C. Rubin Observatory Legacy Survey of Space and Time (Ž. Ivezić et al. 2019), and the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope High Latitude Imaging Survey (R. Akeson et al. 2019), aim to achieve high precision in cosmological measurements from weak lensing observations. High-redshift observations, such as those from JWST (J. P. Gardner et al. 2023), further highlight the importance of effectively removing the IA contribution for the weak lensing analysis with the source galaxies over a wide redshift range. Therefore, understanding and isolating the effect of IA has become an urgent and crucial challenge.

Although IAs introduce systematic errors in weak lensing measurements, they have recently been recognized as a valuable tool for cosmological investigations. For instance, IAs can offer insights into primordial non-Gaussianity and enable the extraction of cosmological information from observations of baryon acoustic oscillations (see, e.g., N. E. Chisari & C. Dvorkin 2013; F. Schmidt et al. 2015; T. Okumura et al. 2019; K. Akitsu et al. 2021; T. Kurita & M. Takada 2023). T. Okumura & A. Taruya (2022) demonstrated that incorporating IA and the kinematic Sunyaev–Zel’dovich effect can place more stringent constraints on dark energy and gravity models.

The IA for early-type galaxies is successfully described by the linear alignment (LA) model, which assumes that the intrinsic shape of a galaxy is determined at the epoch of galaxy formation (C. M. Hirata & U. Seljak 2004). In the LA model, the shapes (orientation and ellipticity) of early-type galaxies are aligned in response to the local tidal field through tidal stretching. In contrast, late-type galaxies acquire the angular momentum under the influence of the tidal field, as described by the tidal torquing mechanism (e.g., P. Catelan et al. 2001; R. G. Crittenden et al. 2001; J. Bailin et al. 2005; J. Lee & U.-L. Pen 2008; S. Codis et al. 2015a). Assuming that their observed ellipticity is determined by the spin orientation, the resulting alignment is modeled as quadratic rather than linear. In this case, the IA signal is expected to be zero in the shape–density correlation, as it is proportional to the cubic of the linear overdensity. Indeed, previous studies have confirmed that late-type galaxies exhibit null or negligible signals of IAs (e.g., R. Mandelbaum et al. 2011; M. Tonegawa & T. Okumura 2022; S. Samuroff et al. 2023).

In the LA model, the strength of IA is quantified by the amplitude parameter, ALA, which relates the galaxy shapes to the tidal field induced by the matter density. Observations and simulations suggest that the ALA depends on galaxy properties such as color, luminosity, halo mass, and redshift (e.g., S. Singh et al. 2015; N. Chisari et al. 2016; D. Piras et al. 2018; H. Johnston et al. 2019; J. Yao et al. 2020; M. C. Fortuna et al. 2021; S. Samuroff et al. 2021; M. Tonegawa & T. Okumura 2022; S. Samuroff et al. 2023; M. Tonegawa et al. 2025). This finding suggests that IA may result from the formation and evolution of galaxies through their interactions with the large-scale structure. Therefore, a detailed understanding of IA is essential for a comprehensive picture of galaxy formation in the Universe. Moreover, it is important to characterize the redshift evolution of the IAs because recent observations tend to cover a wide range of redshifts, which requires a model for redshift-dependent bias to weak lensing. To summarize, the understanding of the strength and evolution of IA is key to advancing our knowledge of not only the weak lensing but also galaxy formation and evolution.

Previous observations found a nearly constant amplitude of IA up to z ∼ 0.7 (B. Joachimi et al. 2011; S. Singh et al. 2015; S. Samuroff et al. 2023; F. Hervas Peters et al. 2025) for early-type galaxies. High-z observations, however, report stronger IA signals than lower redshifts, implying a potential redshift dependence of the IA according to the LA model predictions (J. Yao et al. 2020; M. Tonegawa & T. Okumura 2022). Using a dark matter-only simulation, T. Kurita et al. (2021) found a redshift evolution in ALA for subhalos. Examining whether a similar trend appears in galaxies of hydrodynamical simulations would be interesting to do. Although less decisive due to the influence of various subgrid physics and numerical solvers, studies based on hydrodynamical simulations seem to show a weaker redshift dependence of the IA (A. Tenneti et al. 2015b; N. Chisari et al. 2016; S. Samuroff et al. 2021). The misalignment between galaxies and subhalos may be related to this difference (T. Okumura & Y. P. Jing 2009).

The goal of this work is to study the redshift dependence of the IA of early-type galaxies and dark matter subhalos (dark matter components of galaxies) in the same simulation framework. We use a cosmological hydrodynamical simulation to measure the IA of early-type galaxies and their host dark matter subhalos, and investigate their redshift evolution. We analyze the evolutionary features of IA with respect to redshift, comparing our results with the findings of previous works. By examining the redshift dependence, we aim to understand how the evolution and physical properties of galaxies affect their IAs. As we are interested in the redshift evolution of IAs, we focus mainly on early-type galaxies, which exhibit measurable and redshift-dependent IA signals.

This paper is structured as follows: In Section 2, we introduce the high-resolution hydrodynamical simulation Horizon Run 5 (HR5) and describe the method for selecting early-type galaxies within HR5. Section 3 details the approach for measuring the shapes of galaxies and dark matter subhalos. We define the shape–density cross correlation, a two-point statistical method used to measure the IA. This section also outlines the theoretical model of the IA and explains the procedure for estimating its amplitude. In Section 4, we investigate the properties of the sample, and we show the results of the IA measurement and the amplitude for early-type galaxies and dark matter subhalos. Section 5 focuses on the analysis and discussion of the findings from Section 4, where we compare our results with previous studies and discuss some caveats on the origin of redshift evolution and the timescale of the IA. Finally, we summarize the key findings and propose directions for future research in Section 6. In the Appendices A and B, we verify the technical issues in our results. Appendix C addresses one of the caveats discussed in Section 5.

2. Data

2.1. HR5 Simulation

In this study, we use the high-resolution cosmological hydrodynamical simulation, HR5 (J. Lee et al. 2021), to investigate the IAs of galaxies and their hosting dark matter subhalos. HR5 is performed with a modified version of the RAMSES code (R. Teyssier 2002), which employs an adaptive mesh refinement (AMR) algorithm for higher resolutions in the zoom-in region. The simulation traces the gravitational and hydrodynamic evolution of cosmic matter down to the redshift of z = 0.625 in a cubic box of a side length of 717 h−1 cMpc. For a higher-resolution evolution, a volume of a nearly square-rod shape is set as a “zoom-in" region with dimensions (717, 81, 87) h−1 cMpc. HR5 maintains a nearly constant resolution down to 1 kpc for the dark matter and gas.

The simulation adopts cosmological parameters consistent with the Planck 2016 results (Planck Collaboration et al. 2016), with Ωm = 0.3, ΩΛ = 0.7, and H0 = 68.4 km s−1 Mpc−1. Initial conditions are generated using the MUSIC package (O. Hahn & T. Abel 2011). Dark matter halos are identified using the friends-of-friends algorithm (M. Davis et al. 1985; E. Audit et al. 1998), and galaxies are identified with an improved physically self-bound (PSB) (J. Kim & C. Park 2006)-based galaxy finder, pGalF (J. Lee et al. 2021; J. Kim et al. 2023).

All dark matter particles are identical in mass, whereas the stellar particles exhibit slight variations in mass due to mass loss (by stellar winds and supernova (SN) explosions) or a different amount of gas used for the star formation. In the zoomed region, the mass of the dark matter particle is 6.89 × 107 M⊙, while the mass of the stellar particle is, on average, about 106 M⊙.

Galaxy merger trees are constructed based on the stellar particles using the tree building algorithm, ySAMtm (J. Lee et al. 2014; C. Park et al. 2022; J. Kim et al. 2023). For halos with no stellar particles, we trace their progenitors using their most bound dark matter particles (S. E. Hong et al. 2016). HR5 initially has a based level of 13, which corresponds to 8192 grid cells on a side in the zoomed region, and the grid level decreases to 8 (256 grid cells on a side) in the background volume. Dark matter particle mass increases by a factor of 8 with each grid level decrease. Further details on the HR5 simulation can be found in J. Lee et al. (2021).

2.2. Early-type Galaxy Selection

We select these galaxies from the HR5 galaxy catalog as follows. We first select galaxies by imposing the stellar mass criterion. To have a good IA signal, we restrict our galaxy sample to have M⋆ ≥ 1010 M⊙, which corresponds to about 5000 stellar particles. The most massive subhalo sample tends to show the highest IA amplitude (N. Chisari et al. 2015; A. Tenneti et al. 2015a, 2015b).

As the simulation is running down to the final redshift, the low-level dark matter particles outside of the zoomed-in region (therefore, they have a larger mass) may infiltrate and contaminate the boundaries of the zoomed region more seriously. This may affect the kinematics of stellar particles of galaxies. To minimize this effect, we flag galaxies that are at least 2.052 h−1 cMpc away from low-level dark matter particles. This flag is used to remove contaminated galaxies, resulting in a clean sample consisting exclusively of level 13 particles, which is used in the subsequent analysis. When a galaxy is excluded, we assign more weight to its neighboring galaxy to compensate for the exclusion.

Also, some ongoing mergers may not be relaxed, and early-stage mergers can therefore be misidentified during galaxy identification, introducing potential biases. To mitigate this effect, we use the asymmetry parameter for visual inspection and exclude unrelated systems.

To classify star-forming main-sequence and quiescent galaxies, the diagram of star formation rate (SFR) and stellar mass has widely been applied (E. Daddi et al. 2007; D. Elbaz et al. 2007; K. G. Noeske et al. 2007). This approach appears to be reliable for selecting early-type galaxies. However, some of the early-type galaxies undergo active star formation, which is due to external origin-like galaxy mergers and gas accretion from the cosmic web (Y. H. Lee et al. 2023). Also, some late-type galaxies have low star formation activities (E. D. Paspaliaris et al. 2023). Therefore, we choose to use another criterion based on kinematics. Because early-type galaxies are considered to be supported by the stellar velocity dispersion, we utilize the ratio (∣Vr/σV∣) between the rotational velocity and the velocity dispersion to refine the classification of early-type galaxies. We note that our criterion does not incorporate the Sérsic index for classifying galaxies based on their spatial morphology (C. Park et al. 2022).

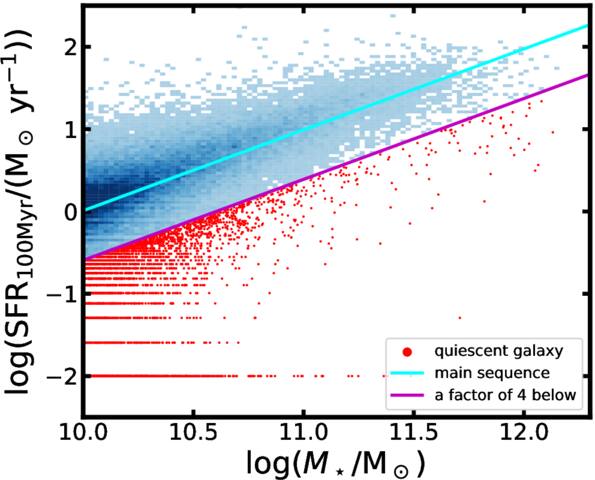

Figure 1 shows the SFR–stellar mass diagram for HR5 galaxies after applying the mass threshold at z = 0.625. We plot the SFR averaged over 100 Myr. We perform a least-squares fit to identify the star-forming main sequence, and define quiescent galaxies as those lying in a factor of four below the main sequence to accommodate observational findings (e.g., E. Kim et al. 2017; Y. H. Lee et al. 2023).

Figure 1. A distribution of SFR as a function of stellar mass of HR5 galaxy at z = 0.625. The value of SFR is averaged over 100 Myr. The bluish boxes are star-forming galaxies. The cyan line is the main sequence of the star-forming galaxies, and the magenta line marks the level that is one-fourth of the main sequence. The red dots are for quiescent galaxies. Note that galaxies with zero SFR at  for the practical display on the logarithmic scale.

for the practical display on the logarithmic scale.

Download figure:

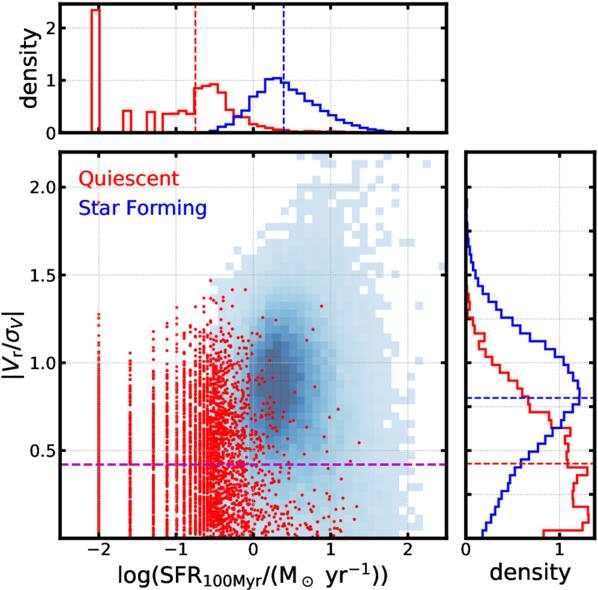

Standard image High-resolution imageAs mentioned earlier, some of the early-type galaxies could experience star formation. Therefore, we may miss them according to the SFR criteria. Therefore, we supplement the method with the kinematic morphology, ∣Vr/σV∣. The values of Vr and σV of a galaxy are calculated from the stellar components within the radial range R1/3 < r < R2/3 in the cylindrical coordinate by setting the direction of angular momentum as the z-axis, where R1/3(2/3) represents the radius that encloses one-third (two-thirds) of the galaxy's stellar mass. Figure 2 displays star-forming galaxies and quiescent galaxies on the plane of SFR versus ∣Vr/σV∣. Quiescent galaxies are distinct compared to star-forming galaxies in the kinematic morphology. The majority of quiescent galaxies are distributed under ∣Vr/σV∣ = 0.5, while star-forming galaxies show a skewed Gaussian distribution centered at ∣Vr/σV∣ = 0.79. For early types, we select ∣Vr/σV∣ = 0.42, which is identical to the median of the distribution of quiescent galaxies.

Figure 2. A distribution of star-forming galaxies and quiescent galaxies on the plane of the SFR and ∣Vr/σV∣. Similar to Figure 1, galaxies with zero SFR are located at  . The top and right panels show the normalized histogram of each galaxy type with the median denoted as dashed lines. The magenta dashed line represents the criterion for an early-type galaxy (∣Vr/σV∣ = 0.42).

. The top and right panels show the normalized histogram of each galaxy type with the median denoted as dashed lines. The magenta dashed line represents the criterion for an early-type galaxy (∣Vr/σV∣ = 0.42).

Download figure:

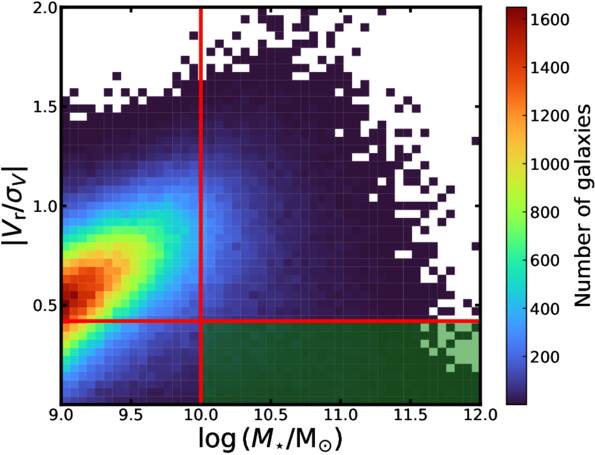

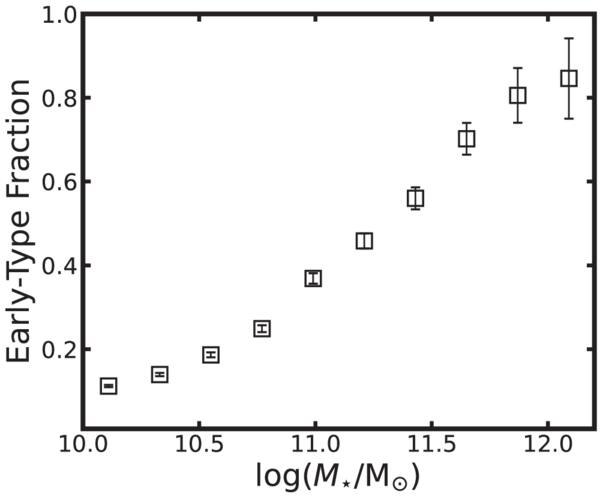

Standard image High-resolution imageFigure 3 shows the final criteria used to select early-type galaxies at z = 0.625, with ∣Vr/σV∣ plotted as a function of stellar mass. Galaxies satisfying the conditions for both stellar mass and kinematic ratio are highlighted in green, representing massive early-type galaxies. In Figure 2, we may confirm our sample selection using SFR. Figure 4 displays the fraction of early-type galaxies as a function of stellar mass, demonstrating that the fraction increases with stellar mass (P. B. Nair & R. G. Abraham 2010; B. Vulcani et al. 2011; J. Pfeffer et al. 2023; J. H. Lee et al. 2024). The same selection criteria are applied to all redshifts for a consistent analysis of early-type galaxies. Table 1 gives the sample size at different redshifts. We note that the number of early-type galaxies is different from that of hosting subhalos at some redshifts. In HR5, there are some galaxies with very few dark matter particles, which are called dark matter-deficient galaxies. The number of dark matter particles in these galaxies is not enough to measure the shapes. Therefore, such objects (2, 1, and 4 dark matter subhalos at z = 1.0, 1.5, and 2.0) are excluded when conducting analyses.

Figure 3. A selection plot of early-type galaxies with the stellar mass (x-axis) and the kinematic ratio (y-axis) at z = 0.625. The red vertical line indicates the stellar mass cut, while the red horizontal line marks the galaxy kinematics cut. The green-shaded region represents the distribution of galaxies that satisfy both criteria and are thus selected for analysis. We use a threshold value of ∣Vr/σV∣ = 0.42, which is determined by the distribution of quiescent galaxies as shown in Figure 2.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageFigure 4. A plot of fractions of early-type galaxies as a function of stellar mass. The fraction increases with stellar mass, a trend consistently observed across different redshifts. The error bars are obtained from bootstrap sampling.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageTable 1. The Number of Galaxies and Hosting Subhalos with M⋆ ≥ 1010 M⊙

| z | Total Galaxy | Early Type | Hosting Subhalo |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.625 | 37,462 | 5335 | 5335 |

| 1.0 | 33,673 | 4469 | 4467 |

| 1.5 | 26,469 | 3562 | 3561 |

| 2.0 | 20,023 | 2617 | 2613 |

| 2.5 | 13,397 | 1365 | 1365 |

Download table as: ASCIITypeset image

3. Method

3.1. Shape Measurement

The accurate measurement of galaxy shapes is essential for the study of both the weak lensing and the IA. In observations, various techniques are used to measure galaxy shapes. One method involves applying model-fitting algorithms, such as lensfit (L. Miller et al. 2007, 2013) and im3shape (J. Zuntz et al. 2013), to the observed surface brightness distribution. Another approach is to directly measure the ellipticity using the quadrupole moments of the surface brightness (D. Kirk et al. 2015).

In simulations, the inertia tensor is widely used to parameterize galaxy shapes (e.g., J. Bailin & M. Steinmetz 2005; A. Kiessling et al. 2015). In this study, we implement this method to measure the projected shapes of galaxies and dark matter subhalos. The reduced inertia tensor is computed to quantify shape parameters of galaxies and subhalos using the positions and masses of stellar and dark matter particles. It is defined as follows:

where mk is the mass of the kth particle and xk,i is the ith component of the “projected” position vector of the particle with respect to the center of mass. The term rk denotes the weighted distance from a particle to the center of the galaxy or dark matter subhalos.

The inertia tensor has two eigenvectors (ea and eb) and their corresponding eigenvalues (λa and λb). The axis ratio of the major and minor axes of the projected ellipse is obtained as  . From now on, we assume λa ≥ λb. In the process of shape measurement, we initially adopt the spherical weighting,

. From now on, we assume λa ≥ λb. In the process of shape measurement, we initially adopt the spherical weighting,

and repeat applying the elliptical weighting in the iteration process,

where  and

and  . We iteratively measure the shape, updating rk until the axis ratio, q ≡ b/a, converges within 0.1%. In this calculation, we simply assume the x-axis of the simulation coordinate as the line-of-sight direction. The inertia tensor is, then, computed using the projected positions of particles on the y–z plane, and the ellipticity is calculated by treating the inertia tensor elements as quadrupole moments.

. We iteratively measure the shape, updating rk until the axis ratio, q ≡ b/a, converges within 0.1%. In this calculation, we simply assume the x-axis of the simulation coordinate as the line-of-sight direction. The inertia tensor is, then, computed using the projected positions of particles on the y–z plane, and the ellipticity is calculated by treating the inertia tensor elements as quadrupole moments.

We adopt the relation between the ellipticity and the position angle as follows:

where e1, e2 represent real and imaginary components of the ellipticity and θ means the position angle of a galaxy. To minimize the influence of outer substructures on the shape measurements, we limit the member particles used in Equation (1). For galaxies, the boundary is set at three times the 3D stellar half-mass radius,  , ensuring that at least 80% of the stellar particles are included. For dark matter subhalos, it is set at 20 times

, ensuring that at least 80% of the stellar particles are included. For dark matter subhalos, it is set at 20 times  , where we use at least 60% of member dark matter particles for most of the dark matter subhalos. These limiting values are chosen to reduce contamination from clumpy structures of the outer part of galaxies and subhalos while ensuring that a sufficient number of particles are included to maintain the accuracy of shape measurements.

, where we use at least 60% of member dark matter particles for most of the dark matter subhalos. These limiting values are chosen to reduce contamination from clumpy structures of the outer part of galaxies and subhalos while ensuring that a sufficient number of particles are included to maintain the accuracy of shape measurements.

3.2. Two-point Statistics

We use two-point statistics to quantify the IA of galaxies. The modified Landy–Szalay estimator (S. D. Landy & A. S. Szalay 1993) is used to measure the shape–density cross-correlation function (R. Mandelbaum et al. 2006; B. Joachimi et al. 2011; S. Singh et al. 2015):

where r represents the separation vector of a galaxy pair. The term RR represents the pair count of randomly distributed points. The term S+D means the sum of the + component of the jth galaxy that is measured with the ith galaxy:

where wj indicates the normalized weight factor of the jth galaxy correcting for the exclusion of contaminated galaxies. The term  represents the relative ellipticity of the jth galaxy viewed from the ith galaxy in the sample,

represents the relative ellipticity of the jth galaxy viewed from the ith galaxy in the sample,

where e1 and e2 indicate the ellipticity of the jth galaxy, and φ means the position angle between the line of galaxy pair and the reference axis of the projection plane (y-axis).

The covariance matrix of the two-point correlation function is computed using the jackknife resampling method. We define a “clean” region where the low-level contamination is minimized. The region has a volume of  . For the jackknife resampling, we divide the region into 80 sub-boxes of size

. For the jackknife resampling, we divide the region into 80 sub-boxes of size  , which are sufficient in number and volume to estimate the covariance matrix.

, which are sufficient in number and volume to estimate the covariance matrix.

3.3. NLA Model

The LA model has been one of the most prevailing approaches to the IA of galaxy shapes (P. Catelan et al. 2001; C. M. Hirata & U. Seljak 2004; J. Blazek et al. 2011). In the model, the intrinsic shape of a galaxy is determined by the tidal field of the large-scale structure at the formation epoch of the galaxy. Instead of using the linear power spectrum as in the LA model, the nonlinear alignment (NLA) model implements the nonlinear power spectrum (S. Bridle & L. King 2007; C. M. Hirata et al. 2007) for a better description of the clustering of the matter field.

In the matter-dominated era, the intrinsic shape ( ) of a galaxy is related to the primordial gravitational potential (ϕp) in the following way:

) of a galaxy is related to the primordial gravitational potential (ϕp) in the following way:

where C1 is a normalization factor. The primordial potential is connected with the overdensity δ(k) through the Poisson equation in the Fourier space,

where a means the cosmic scale factor,  is the mean matter density at z, and D(z) is the linear growth factor normalized as D(z = 0) = 1. According to C. M. Hirata & U. Seljak (2004), the cross-power spectrum between the shape and density has the form

is the mean matter density at z, and D(z) is the linear growth factor normalized as D(z = 0) = 1. According to C. M. Hirata & U. Seljak (2004), the cross-power spectrum between the shape and density has the form

The theoretical modeling of IA correlations is well studied in three dimensions (T. Okumura & A. Taruya 2020; T. Okumura et al. 2020). We adopt this formalism to convert the power spectrum (PδI) of C. M. Hirata & U. Seljak (2004) into the cross correlation of shape and density in three dimensions as follows:

where bg means the galaxy bias, and μ represents the cosine between separation vector and line-of-sight direction indicating the angular dependence term (1 − μ2) corresponding to the shape projection onto a plane (T. Okumura et al. 2019). The term, j2(kr), means the second-order spherical Bessel function. We use the positions of galaxies as tracers of the density field. To account for the bias between galaxy density and matter density, we adopt the linear galaxy bias.

4. Results

4.1. Sample Analysis

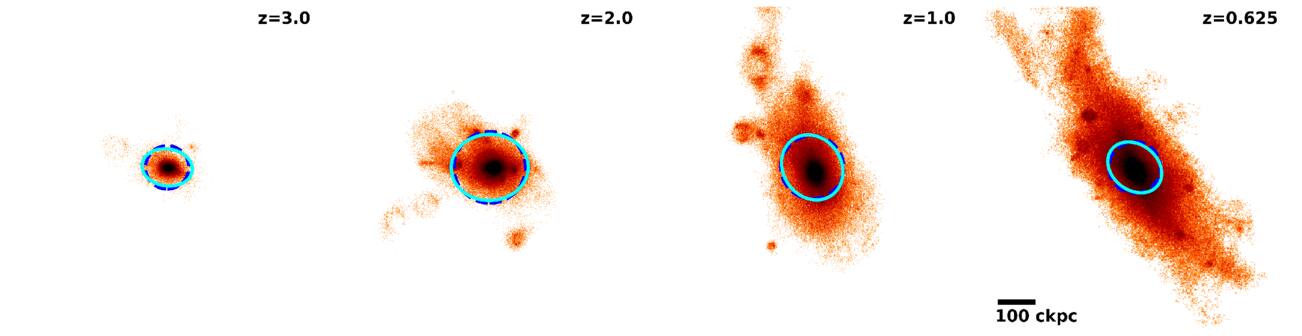

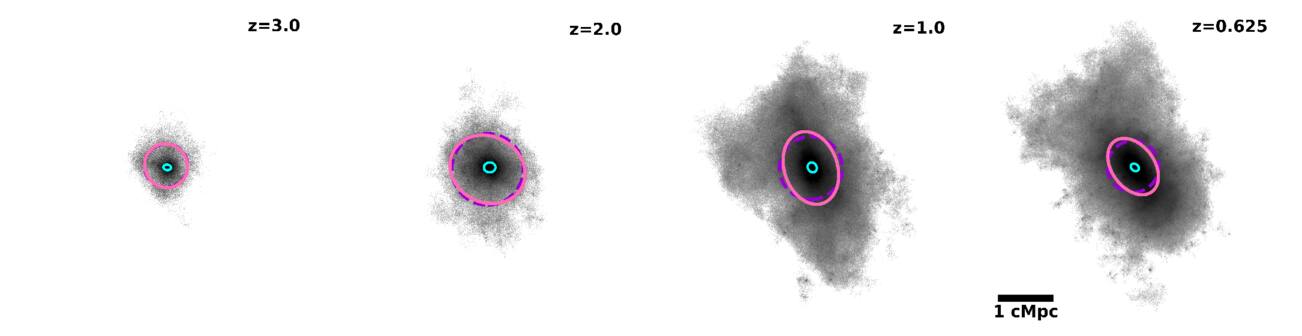

In this section, we present the statistical properties of the shapes of galaxies and dark matter subhalos. We illustrate the evolutionary phase of the progenitor of the most massive galaxy found at z = 0.625 and its hosting dark matter subhalo in Figures 5 and 6, respectively. As described in Section 3.1, galaxy shapes are determined using the member stellar particles within three times the stellar half-mass radius, but the measurement for dark matter subhalos extends to 20 times the stellar half-mass radius. The shapes are visually represented by solid ellipses in the figures. The oblateness and position angle of the measured shapes align well with the images of the galaxy and dark matter subhalo, demonstrating the fairness of shape measurements.

Figure 5. A distribution of stellar particles of the most massive galaxy at z = 0.625 with M⋆ = 1.436 × 1012 M⊙. Its progenitors are traced back to z = 1, 2, and 3. The blue dashed circle represents the boundary of particle selection, which has the value of  for a galaxy. The shape of a galaxy is determined using its inertia tensor iteratively. We obtain the shape parameters such as ellipticity, major and minor axes, and position angle. The cyan solid ellipse illustrates the resulting shape.

for a galaxy. The shape of a galaxy is determined using its inertia tensor iteratively. We obtain the shape parameters such as ellipticity, major and minor axes, and position angle. The cyan solid ellipse illustrates the resulting shape.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageFigure 6. Similar to Figure 5, but for the hosting dark matter subhalo. The boundary of particle selection for the dark matter subhalo is  denoted as the dark-violet dashed circle. The resulting shape is shown with the bright-violet solid ellipse. We add the shape of the galaxy with the cyan solid ellipse for comparison.

denoted as the dark-violet dashed circle. The resulting shape is shown with the bright-violet solid ellipse. We add the shape of the galaxy with the cyan solid ellipse for comparison.

Download figure:

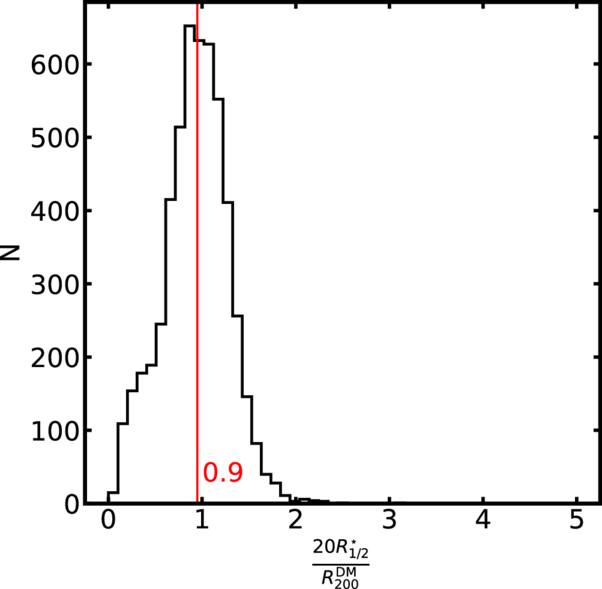

Standard image High-resolution imageRather than directly using the half-mass radius of dark matter, we use the half-mass radius of stellar matter for the subhalo analysis in order to reconcile with observations, which mostly use the half-light radius (which is converted to half-mass radius with a proper mass-to-light ratio). Figure 7 shows a distribution of the ratio between  and

and  for dark matter subhalos. We note that for 82% of subhalos, more than 80% of member particles are used for shape measurements. Figure 7 indicates that 20 times of

for dark matter subhalos. We note that for 82% of subhalos, more than 80% of member particles are used for shape measurements. Figure 7 indicates that 20 times of  closely approximates to

closely approximates to  for most of the subhalos. The choice of aperture is critical, as the subhalo shape is highly sensitive to the extent of the boundary. A smaller boundary significantly weakens the IA signal, rendering it less prominent than in the case of galaxies. It is well established that dark matter subhalos exhibit higher amplitudes of shape–density correlations than galaxies (T. Okumura & Y. P. Jing 2009; (T. Okumura et al. 2009; A. Tenneti et al. 2015a). Our choice of

for most of the subhalos. The choice of aperture is critical, as the subhalo shape is highly sensitive to the extent of the boundary. A smaller boundary significantly weakens the IA signal, rendering it less prominent than in the case of galaxies. It is well established that dark matter subhalos exhibit higher amplitudes of shape–density correlations than galaxies (T. Okumura & Y. P. Jing 2009; (T. Okumura et al. 2009; A. Tenneti et al. 2015a). Our choice of  reproduces a similar behavior (Section 4.2).

reproduces a similar behavior (Section 4.2).

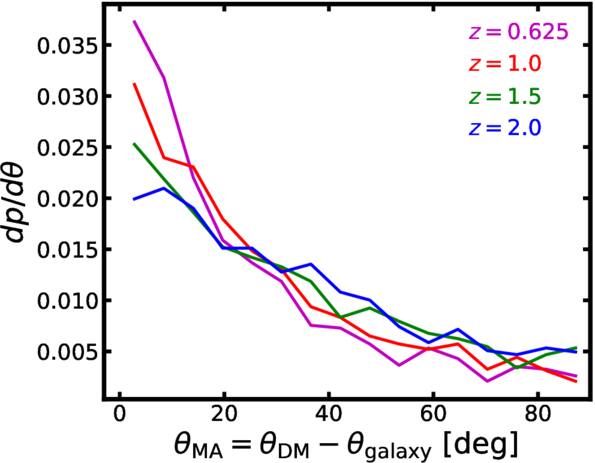

Figure 7. A histogram of the ratio of  and

and  . It is concentrated around unity, which demonstrates that our selection criterion (based on

. It is concentrated around unity, which demonstrates that our selection criterion (based on  ) is physically reasonable.

) is physically reasonable.

Download figure:

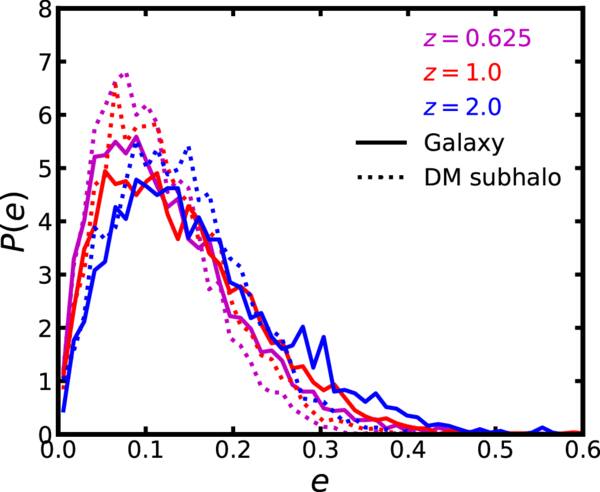

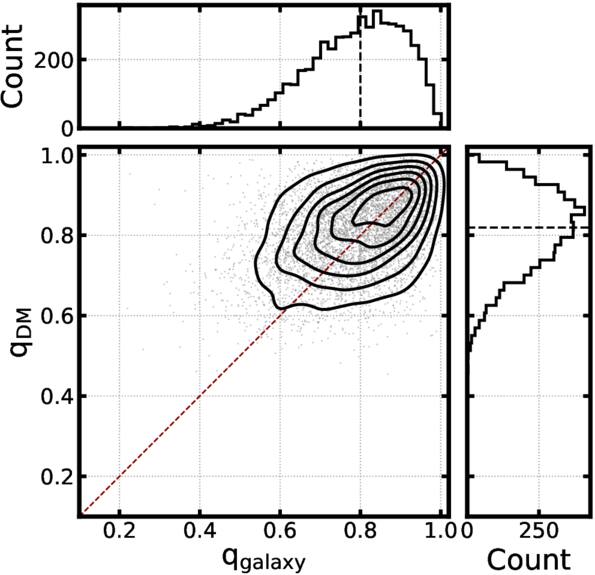

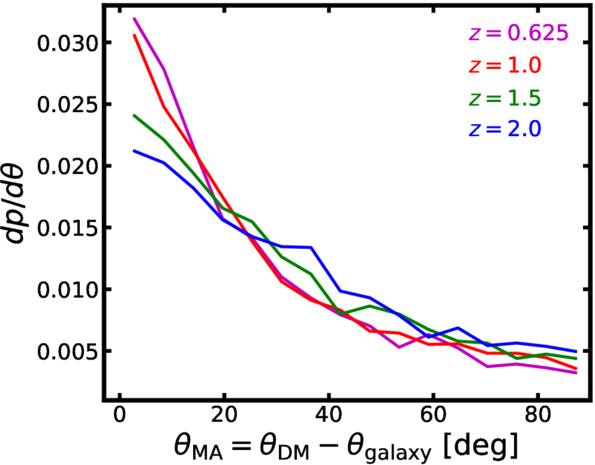

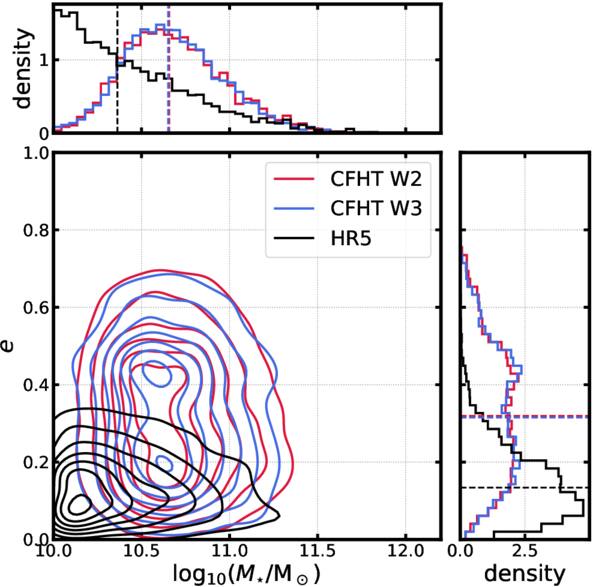

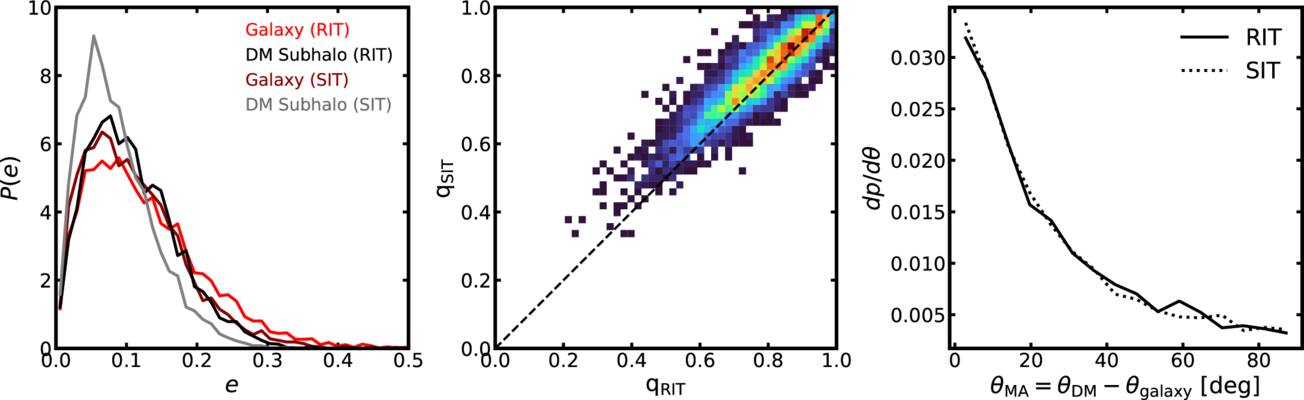

Standard image High-resolution imageWe analyze ellipticity distributions of galaxies and dark matter subhalos in Figure 8. We find that galaxies and dark matter subhalos become more spherical with time. We analyze the effect of various shape measurements on our results in Appendix A. Figure 9 compares the distribution of axis ratios for galaxies and dark matter subhalos. These results indicate that the shape of a galaxy tends to be more elliptical than the hosting subhalo (C. Pulsoni et al. 2021). We note that the shape measurements for galaxies are relatively robust because of a large number of particles involved, as we focus on massive galaxies with M⋆ ≥ 1010 M⊙. In contrast, some subhalos have fewer than 100 member particles, which can introduce significant noise in the shape measurement. Figure 10 demonstrates that HR5 galaxies and subhalos experience some misalignment in the position angle as found in previous studies (T. Okumura & Y. P. Jing 2009; A. Tenneti et al. 2014; A. K. Bhowmick et al. 2020). We find that the shapes of early-type galaxies become more aligned with surrounding dark matter subhalos with time.

Figure 8. Distributions of the total ellipticity,  , of galaxies (solid lines) and dark matter subhalos (dotted lines) at z = 0.625, 1.0, and 2.0. Dark matter shapes are rounder than galaxies. Both become rounder as they evolve with time.

, of galaxies (solid lines) and dark matter subhalos (dotted lines) at z = 0.625, 1.0, and 2.0. Dark matter shapes are rounder than galaxies. Both become rounder as they evolve with time.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageFigure 9. A distribution of the axis ratio, q = b/a, of galaxies and dark matter subhalos. Dashed lines in the top and right panels represent the median of the distribution. The axis ratio for dark matter subhalos, qDM, shows a higher concentration than qgalaxy, which indicates dark matter subhalos are rounder than early-type galaxies. This feature is consistent with Figure 8.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageFigure 10. Distributions of misalignment angle for 2D shapes of galaxies and dark matter subhalos at z = 0.625, 1.0, 1.5, and 2.0. Galaxies are more aligned with dark matter subhalos at lower redshift. About 22% of galaxies are misaligned with their dark matter subhalos by a difference angle greater than θMA = 45° at z = 0.625.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution image4.2. The Two-point Correlation

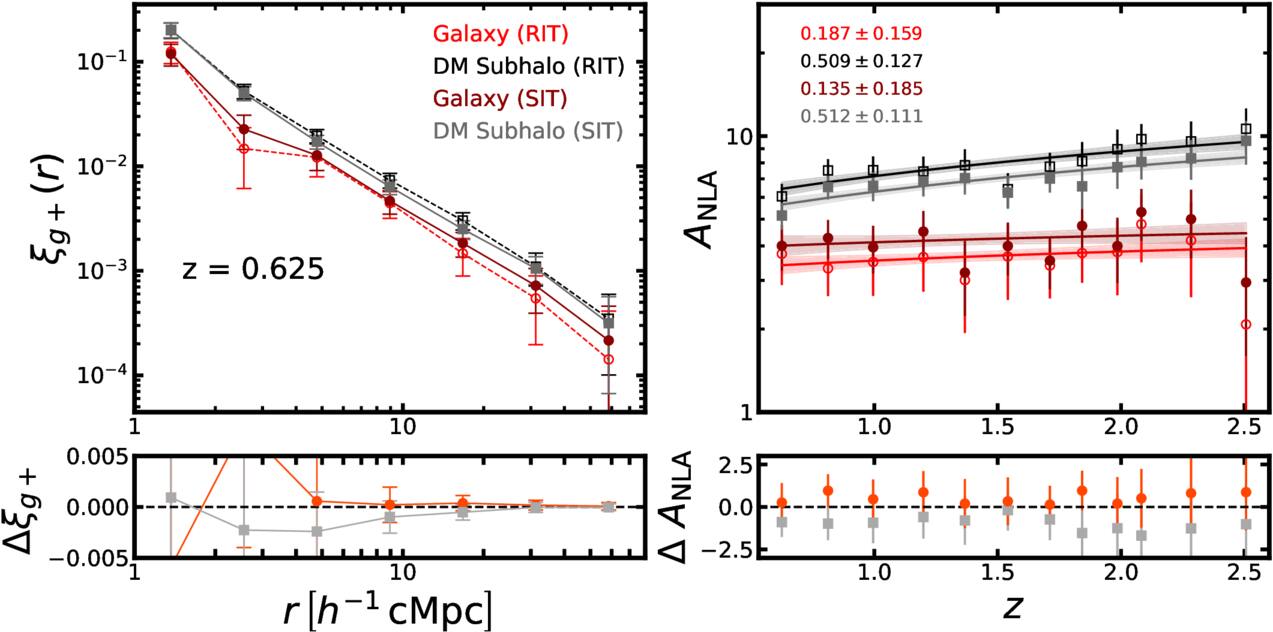

We examine the cross-correlation function, ξg+(r), between intrinsic shapes of galaxies/subhalos and their positions at z = 0.625, 1.0, and 2.0. This quantity is free from the grid-locking effect that occurs in the simulations using the AMR scheme based on the octree mesh in Cartesian coordinates (N. Chisari et al. 2015). We verify this issue in Appendix B.

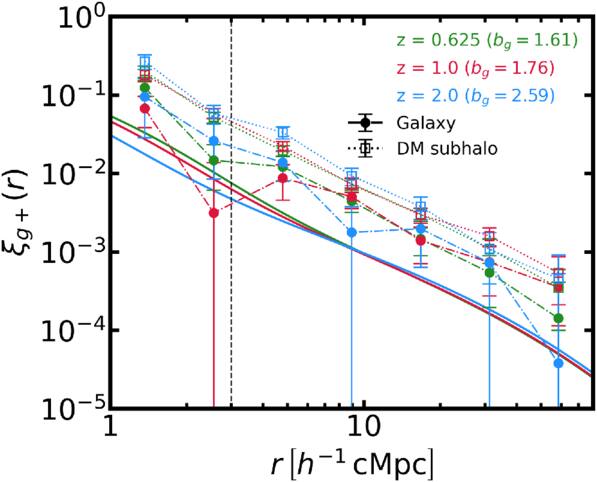

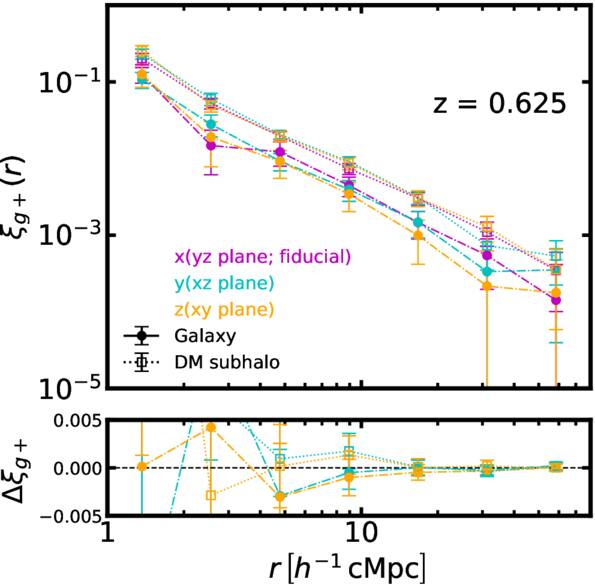

The x-axis of the simulation box is designated as the line-of-sight direction along which projected shapes are measured. The pair separation of interest has a range of r = 1–80 h−1 cMpc. The lower limit is set to exclude the one-halo dominant regime (M. D. Schneider & S. Bridle 2010; A. Tenneti et al. 2015a), and the upper limit ensures that measurements are made in the clean region of HR5. Figure 11 shows the cross-correlation functions for galaxies and subhalos. The error bars show the square root of the diagonal components of the covariance matrix. The IA signal of subhalos is stronger than galaxies. The cross correlation (ξg+) does not show a significant redshift dependence in our analysis. However, the quantity shown in Figure 11 is proportional not only to the amplitude of IA, but also to the galaxy bias (bg). We will discuss this in further detail in Section 5. To assess potential systematic biases related to the choice of the projection axis, we measure the shape along different line-of-sight directions and calculate the IA correlation at z = 0.625, which is displayed in Figure 12. The bottom panel shows the differences between the correlations for alternate projection planes and the fiducial projection direction, x-axis. Our analysis confirms that the choice of the projection direction does not introduce a significant bias into the results.

Figure 11. Cross correlations,  , measured for early-type galaxies (filled circles) and dark matter subhalos (open squares) at redshifts z = 0.625, 1.0, and 2.0. Dark matter subhalos show higher correlations than galaxies. The error bars represent the square root of the diagonal components of the covariance matrix. The solid lines show the theoretical predictions, which are normalized by CHS (see Section 4.3). The vertical dashed line marks r = 3 h−1 cMpc, above which scales are used to obtain the amplitude parameter.

, measured for early-type galaxies (filled circles) and dark matter subhalos (open squares) at redshifts z = 0.625, 1.0, and 2.0. Dark matter subhalos show higher correlations than galaxies. The error bars represent the square root of the diagonal components of the covariance matrix. The solid lines show the theoretical predictions, which are normalized by CHS (see Section 4.3). The vertical dashed line marks r = 3 h−1 cMpc, above which scales are used to obtain the amplitude parameter.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageFigure 12. Similar to Figure 11 but with different directions of projection. (Top panel) The shape–density correlations are measured at z = 0.625. (Bottom) The differences of the correlations from the fiducial (x-) axis are shown. All three correlations are consistent with each other, indicating that the projection axis does not make the systematics.

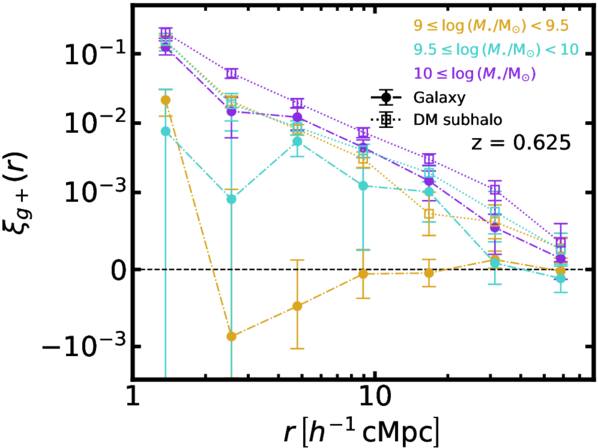

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageFigure 13 shows the dependence of IA on stellar mass. For this plot, the stellar mass is divided into three bins: M⋆ = 109−9.5 M⊙, M⋆ = 109.5−10 M⊙, and M⋆ ≥ 1010 M⊙. The same galaxy selection criteria and the measurement range are applied as used in Figure 11. Our results are consistent with previous findings (A. Tenneti et al. 2015a) showing that the IA signal gets stronger with increasing stellar mass. For galaxies in the lowest mass bin, the IA signal is consistent with zero, indicating no significant alignment. This feature agrees with Figure 4 because the fraction of early-type galaxies increases with the stellar mass. In contrast, subhalos exhibit positive IA correlations across all mass bins, showing a stronger alignment signal even at lower stellar masses of galaxies hosted by the subhalos.

Figure 13. Similar to Figure 11 but with different stellar mass bins, 109−9.5 M⊙, 109.5−10 M⊙, and ≥1010 M⊙. For galaxies, the correlation of the first bin is consistent with zero.

Download figure:

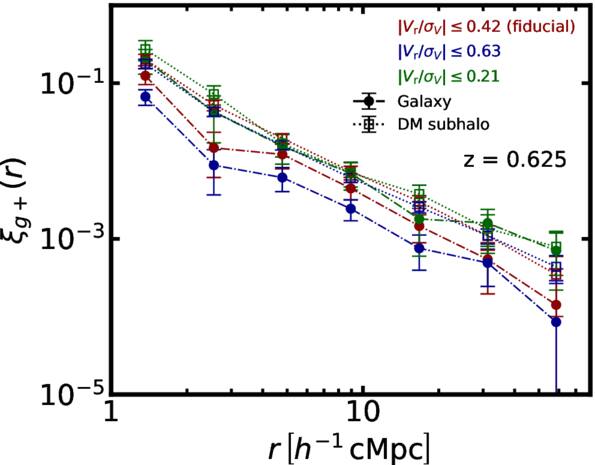

Standard image High-resolution imageFigure 14 illustrates the effect on ξg+ of rotation-supported galaxies. The fiducial selection criterion for early-type galaxies is ∣Vr/σV∣ ≤ 0.42. We find that galaxies with smaller ∣Vr/σV∣ show a higher IA correlation amplitude. The error bars for the low-ratio sample (∣Vr/σV∣ = 0.21) are substantially larger than the other two samples. This is attributed to the smaller sample size, which limits the statistical robustness of the measurements for this subset. In contrast, the IA correlation for dark matter subhalos shows no significant variation across different ∣Vr/σV∣ samples. This is because, even for rotating galaxies, the corresponding dark matter subhalos have little rotational component, making them susceptible to the tidal stretching effect.

Figure 14. Similar to Figure 11 but with a different kinematic morphology criterion. For galaxies, the correlation depends on the fraction of late-type galaxies. Dark matter subhalos do not show sensitivity to ∣Vr/σV∣.

Download figure:

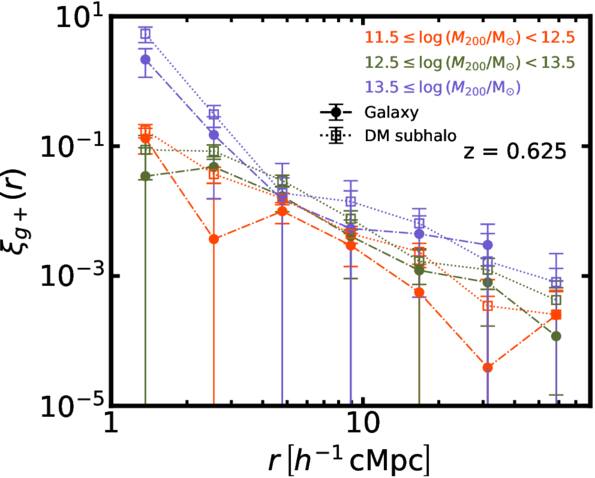

Standard image High-resolution imageWe also investigate the host halo mass dependence of IA correlation in Figure 15. Galaxies and subhalos are selected following the previously described criteria and categorized based on the virial mass of their host halo (M200) into three mass bins: M200 = 1011.5−12.5 M⊙, M200 = 1012.5−13.5 M⊙, and M200 ≥ 1013.5 M⊙. Both galaxies and subhalos show stronger alignment signals with increasing host halo mass. Given the scatter in the stellar-to-halo mass relation, occasional overlaps and inversions in the measured signals at certain points happen.

Figure 15. Similar to Figure 11 but with different halo mass bins, 1011.5−12.5 M⊙, 1012.5−13.5 M⊙, and ≥1013.5 M⊙.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution image4.3. IA Amplitude Parameter

In this subsection, we examine the evolution of the IA strengths for both the galaxies and the subhalos as a function of redshift. As described in Section 3.3, the parameter, C1, which denotes the amplitude of the IA power spectrum, is normalized to a dimensionless parameter, ANLA, as follows:

where  (M. L. Brown et al. 2002; C. M. Hirata & U. Seljak 2004), which is obtained by comparison with SuperCOSMOS (N. C. Hambly et al. 2001). The value of ANLA is determined by comparing the measured shape–density correlation to the corresponding theoretical model. The fitting is performed over the range 3 < r < 80 h−1 cMpc. Because galaxy positions are treated as biased tracers of the underlying density field, the galaxy bias bg is needed for theoretical predictions of ξg+ (Equation (11)). We follow J. Einasto et al. (2023) to measure bg as the square root of the ratio between the galaxy and dark matter density–density correlation functions at 6.84 h−1 cMpc. We apply the same bg for both galaxies and subhalos because each galaxy is hosted by a subhalo. The optimal value of ANLA and its associated uncertainty are obtained through a χ2 minimization process performed over a range of redshifts.

(M. L. Brown et al. 2002; C. M. Hirata & U. Seljak 2004), which is obtained by comparison with SuperCOSMOS (N. C. Hambly et al. 2001). The value of ANLA is determined by comparing the measured shape–density correlation to the corresponding theoretical model. The fitting is performed over the range 3 < r < 80 h−1 cMpc. Because galaxy positions are treated as biased tracers of the underlying density field, the galaxy bias bg is needed for theoretical predictions of ξg+ (Equation (11)). We follow J. Einasto et al. (2023) to measure bg as the square root of the ratio between the galaxy and dark matter density–density correlation functions at 6.84 h−1 cMpc. We apply the same bg for both galaxies and subhalos because each galaxy is hosted by a subhalo. The optimal value of ANLA and its associated uncertainty are obtained through a χ2 minimization process performed over a range of redshifts.

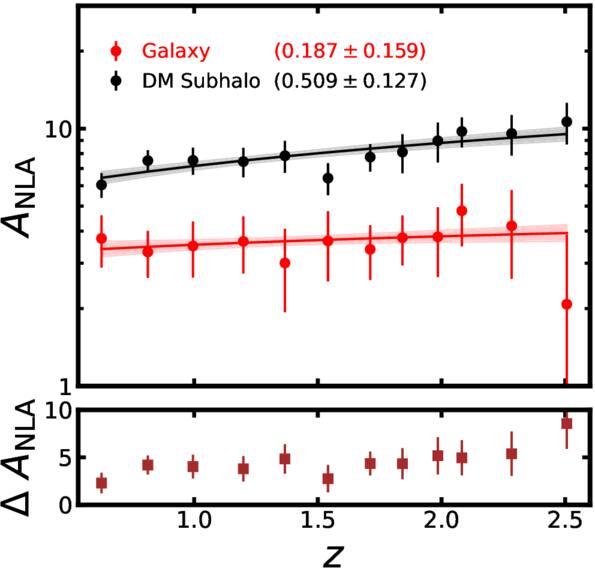

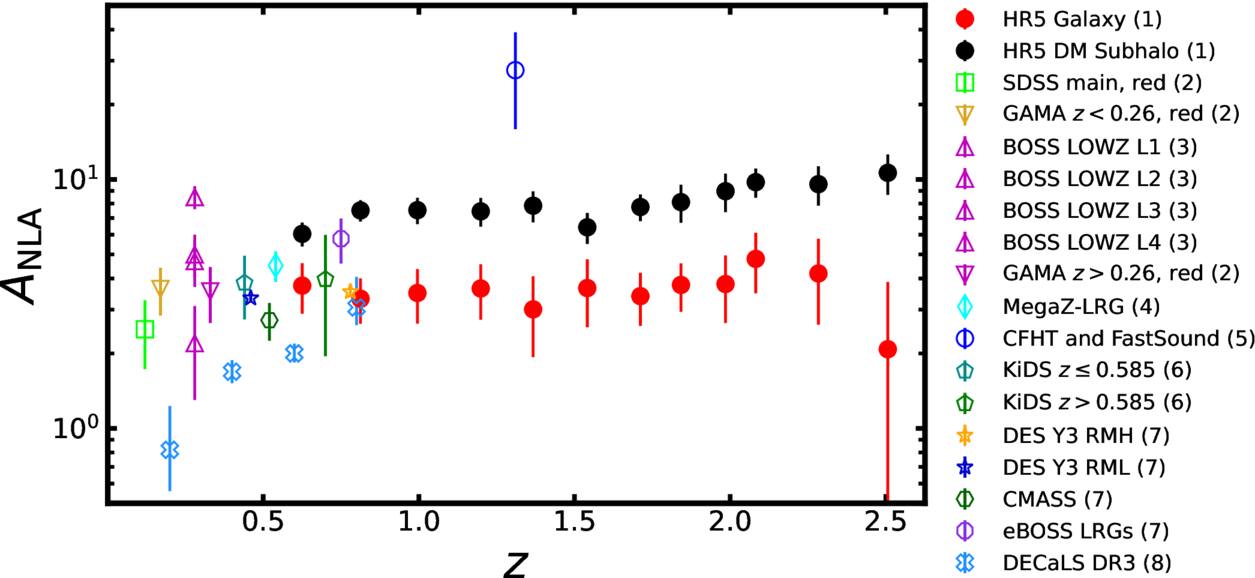

Figure 16 shows the amplitude of the IA (ANLA) as a function of redshift. The evaluation of ANLA stops at z = 2.5 because of the small sample size dropping below 1000 at higher redshifts. Subhalos always exhibit higher ANLA than galaxies, which is consistent with the results presented in Section 4.2. While galaxies show no significant variation across redshifts, subhalos tend to show an increase in ANLA. We perform a weighted least-squares fitting and obtain the power-law slope of 0.187 ± 0.159 for galaxies and 0.509 ± 0.127 for subhalos. We also find that the difference of ANLA between galaxies and subhalos decreases at lower redshifts. This trend is consistent with the decreasing misalignments between galaxies and subhalos as shown in Figure 10. The value of each data point in Figure 16 is listed in Table 2.

Figure 16. IA amplitude parameter, ANLA, as a function of redshift. Red and black dots represent the ANLA of galaxies and dark matter subhalos, respectively. The range of redshift is from 0.6 to 2.5. Galaxies do not show evolutionary features. However, dark matter subhalos show an evolutionary trend across redshifts. It is especially distinct at z > 1.5. The bottom panel shows the difference in ANLA between the galaxy and the dark matter subhalo,  .

.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageTable 2. ANLA for Galaxies and Dark Matter Subhalos with M⋆ ≥ 1010 M⊙

| z | Galaxy | Dark Matter Subhalo |

|---|---|---|

| 0.625 |

|

|

| 0.8 |

|

|

| 1.0 |

|

|

| 1.2 |

|

|

| 1.36 |

|

|

| 1.5 |

|

|

| 1.7 |

|

|

| 1.8 |

|

|

| 2.0 |

|

|

| 2.1 |

|

|

| 2.3 |

|

|

| 2.5 |

|

|

Download table as: ASCIITypeset image

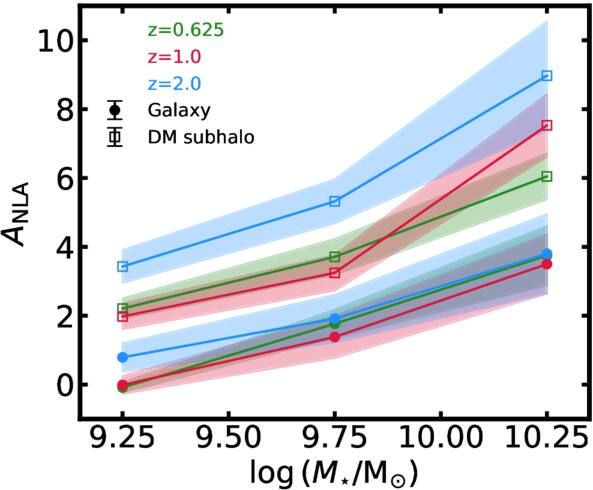

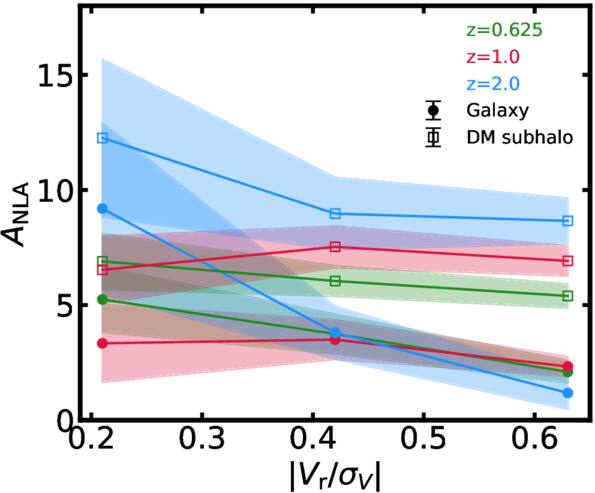

Figures 17 and 18 show the dependence of ANLA on stellar mass and ∣Vr/σV∣, respectively. The amplitudes are measured for the three mass bins as described earlier. As in Figure 13, the amplitude increases with the inclusion of more massive galaxies at all redshifts. This trend, consistent with the results in Section 4.2, confirms that IA becomes stronger for higher-mass galaxies. In Figure 17, galaxies do not show a variation of the ANLA for all mass bins and redshifts. For dark matter subhalos, a nonzero amplitude is observed even in the lowest mass bin. The amplitudes of dark matter subhalos at z = 2.0 are larger than at lower redshifts at all three mass bins.

Figure 17. The stellar mass dependence of ANLA. The mass bins are identical to those in Figure 13. As expected, ANLA tends to increase as mass increases.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageFigure 18. Similar to Figure 17, the kinematic morphology dependence of ANLA is shown. As the ratio increases, ANLA for galaxies decreases due to the effect of disk galaxies, whereas for dark matter, subhalos do not.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageFigure 18 shows a decline in ANLA of galaxies across all redshift ranges as ∣Vr/σV∣ increases, a trend that is consistent with the higher fraction of disk galaxies (blue) at higher ∣Vr/σV∣. If we use a criterion of higher ∣Vr/σV∣, the galaxy sample size is increased. However, it dilutes the alignment signal because of the larger fraction of late-type galaxies in the sample. For dark matter subhalos, this diminishing behavior is not obviously observed even with increasing ∣Vr/σV∣ cuts.

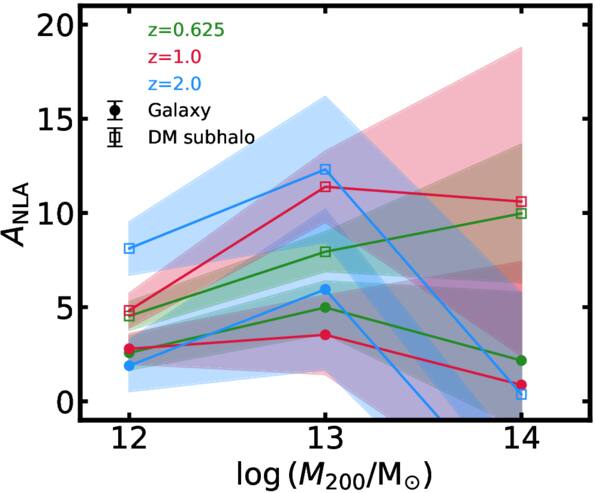

We also investigate the halo mass dependence of ANLA in Figure 19. As halo mass increases from 1012 M⊙ to 1013 M⊙, the amplitude correspondingly increases. While subhalos exhibit a consistent increase in amplitude with redshift, galaxies show negligible evolution with redshift and display only a weak dependence on halo mass. In the highest mass bin, both galaxies and subhalos show decreased amplitude accompanied by significant uncertainties. These features result from limited statistical samples available at higher halo masses and redshifts.

Figure 19. Similar to Figure 17, but the halo mass dependence of ANLA is shown. The x-axis represents the median of each halo mass bin.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution image5. Discussion

5.1. Comparison with Observations

Figure 20 shows our results with observations, which are represented by open symbols with different colors. Our findings match most of the observational results. Some observations, such as those by (J. Yao et al. 2020, blue open crosses) and (M. Tonegawa & T. Okumura 2022, dark blue open circles), show trends inconsistent with the majority, which might be interpreted as indicative of redshift evolution. However, the amplitude parameter strongly depends on galaxy properties such as stellar mass, luminosity, and color, suggesting that different samples of galaxies can lead to large variations of the IA.

Figure 20. Similar to Figure 16, but with the y-axis on a log scale. The open symbols represent observational results. Our results are well matched with observations. We note that J. Yao et al. (2020)'s result overlaps with our results as well as other observations except for the first bin. Also, M. Tonegawa & T. Okumura (2022)'s result deviates from our results. References: (1) This work; (2) H. Johnston et al. (2019); (3) S. Singh et al. (2015); (4) B. Joachimi et al. (2011); (5) M. Tonegawa & T. Okumura (2022); (6) M. C. Fortuna et al. (2021); (7) S. Samuroff et al. (2023); (8) J. Yao et al. (2020).

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageTo further investigate these differences, we examine the sample properties. Figure 21 displays the distributions of stellar mass and ellipticity for HR5 galaxies compared with the CFHTLenS sample used in M. Tonegawa & T. Okumura (2022) within the photometric redshift range of 1.13–1.63. The stellar mass distribution of HR5 differs significantly from that of CFHTLenS, which may explain why the correlation strength is higher than our results. Moreover, the ellipticity distributions of the HR5 galaxies and the CFHTLenS galaxies are notably different. These differences suggest that the observed trend arises from sample variance rather than redshift evolution.

Figure 21. Relations between stellar mass and measured ellipticity. Black lines represent HR5 galaxies. Red and blue lines represent CFHT Wide W2 and W3 fields, respectively. The top panel shows the stellar mass histogram. CFHT galaxies contain more massive galaxies than the HR5 simulation. The right panel shows the distributions of ellipticity, similar to Figure 8. We note that the ellipticity of CFHT galaxies differs from HR5 galaxies, showing many elliptical shapes.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution image5.2. Comparison with Other Simulations

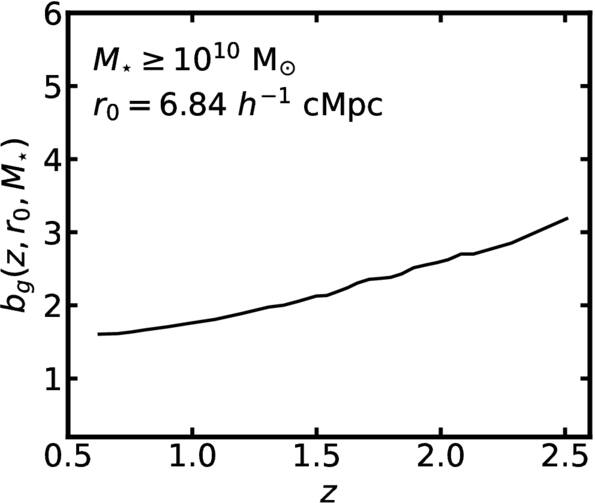

We compare our results with other simulations. In Figure 11, we find that ξg+ has little redshift dependence. We compare our findings with the results of A. Tenneti et al. (2015b) and N. Chisari et al. (2016), who measured the projected correlation. A. Tenneti et al. (2015b) argued that there was no significant redshift dependence. On the other hand, N. Chisari et al. (2016) reported that the evolutionary feature of the projected correlation becomes evident at small scales. However, it should be noted that the scale of interest is different from ours. We focus on r from 3 to 80 h−1 cMpc, which is over the scale of the one-halo alignment, while their works look into a shorter scale from 0.1 to 10 h−1 cMpc. When looking at the correlation at large scales (rp > 3 h−1 cMpc; where rp represents the transverse separation), we find that neither works show manifest redshift evolution of the two-point correlation. In this sense, our finding is consistent with the results of A. Tenneti et al. (2015b) and N. Chisari et al. (2016). The quantity shown in Figure 11 is ξg+(r) ∝ bgANLA, not ξm+(r) ∝ ANLA; thus, it depends on the galaxy bias, which should vary over redshifts for a fixed mass. As in Figure 22, the galaxy bias depends on redshift. The trend of redshift dependence of the galaxy bias is opposite to that of the theoretical power spectrum (Equation (10)), leading to a nearly constant ξg+ with respect to redshifts.

Figure 22. A change in galaxy bias with redshift at fixed mass and correlation radius. Following J. Einasto et al. (2023), we measure the galaxy bias at M⋆ ≥ 1010 M⊙, and r0 = 6.84 h−1 cMpc.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageWe also compare our findings with more recent studies. K. Xu et al. (2023) investigated the projected shape–density correlation of galaxies and dark matter subhalos across different stellar mass ranges using the TNG300-1 simulation. Our results qualitatively agree with theirs, confirming that dark matter subhalos exhibit a stronger IA signal compared to galaxies. They also demonstrated that the misalignment angle depends on both stellar and halo virial masses, with the mean of the misalignment angle increasing toward higher redshift. The decrease in the misalignment angles toward lower redshifts agrees with our findings.

Using the TNG300-1 simulation, F. Rodriguez et al. (2024) investigated the anisotropic correlation function for stellar and dark matter components of central galaxies, which is computed using pairs subtending less than 45° to the directions of the axes. They found that galaxies and subhalos show opposite evolutions of alignments with time. They also showed that these features depend on galaxy color and halo mass. These results indicate that there are different physical processes influencing baryonic and dark matter components, and are consistent with our findings.

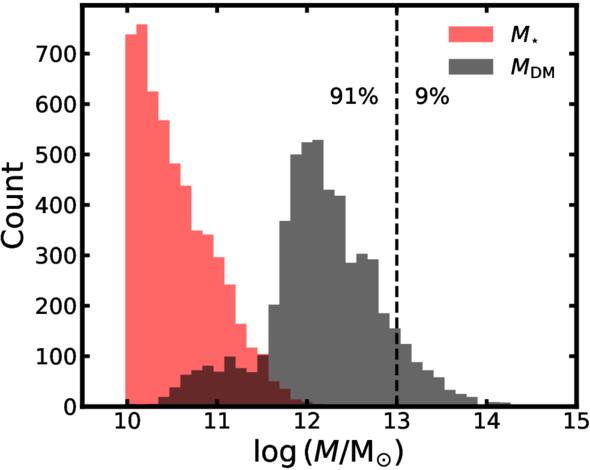

We then discuss the redshift evolution of ANLA. T. Kurita et al. (2021) explored redshift dependence of dark matter subhalos with halo mass and number density using an N-body simulation. They showed that the redshift evolution becomes more pronounced at lower redshifts (see Figure 6 therein). On the other hand, the amplitude became constant beyond z = 1.0. The increasing feature at low redshifts is similar to our findings, while the plateau at high redshifts for the high-mass sample is in contrast with ours. In this study, we use the hydrodynamical simulation, not N-body simulation. In Figure 16, we only consider the stellar mass, not the halo mass. These discrepancies could cause the different trend. Figure 23 shows the distributions of stellar mass of the galaxy and dark matter mass of the subhalo. 91% of subhalos have mass with MDM < 1013 M⊙, while only 9% showing MDM ≥ 1013 M⊙. Thus, the increase at high redshifts for dark matter subhalos is consistent with previous results for low-mass objects.

Figure 23. Mass distributions of galaxies and dark matter subhalos. The black dashed line marks a division of subhalo mass showing different trends with respect to halo mass in T. Kurita et al. (2021).

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageA. Tenneti et al. (2015b) presented that the ANLA of galaxies shows no evolution with redshift. It is similar to our results for HR5. They also showed that different samples lead to different trends, suggesting that the growth of structure and dynamical processes such as galactic mergers may have played a role in this. They argued that, as the misalignment is driven by such processes, the amplitude of IA should also be affected, which is partially reflected in the redshift evolution of ANLA.

S. Samuroff et al. (2021) showed ANLA in Illustris, IllustrisTNG, and MassiveBlack-II simulations. While the results for TNG show no evolution, Illustris and MassiveBlack-II tend to increase with redshift. Illustris contains more late-type galaxies than IllustrisTNG (V. Rodriguez-Gomez et al. 2019). This is primarily due to the less effective regulation of star formation in Illustris, which contributes to this trend. They argued that because of the evolution of the underlying large-scale structure and the growth of halos, the use of a fixed mass cut forced a stricter sample selection at high redshift, which excluded weakly aligned galaxies, leading to redshift evolution. This interpretation is partially consistent with ours if we consider dark matter subhalos only. However, in our study, the IA amplitudes of galaxies do not show redshift evolution. Also, IllustrisTNG shows an evident decrease in ANLA at z < 0.6, after the Universe enters the Λ-dominated era, even considering their red galaxies of TNG only. This epoch is out of our consideration due to the limit of HR5. In this regard, our results are consistent with previous studies. N. Chisari et al. (2016) investigated how ANLA varies depending on the shape measurement method and the galaxy type. They did not find the redshift evolution of the IA when they measured the galaxy shapes via different inertia tensors and investigated the IA amplitude in a redshift range from z = 1 to z = 3. At z < 1, they also showed a similar feature to S. Samuroff et al. (2021). The consistency across the considered redshift range is similar to our results, and the effect of disk galaxies on the IA amplitude shows a similar trend.

5.3. Redshift Evolution

5.3.1. Possible Origin

Here, we discuss the possible origin of the redshift dependence of the IA. We begin with the redshift dependence of the misalignment angle. As we mentioned earlier, galaxies are more aligned with dark matter subhalos at lower redshifts. This trend is consistent with A. K. Bhowmick et al. (2020) and K. Xu et al. (2023). It is known that dynamical processes of galaxies, including the active galactic nuclei (AGN) and SN feedback, can affect misalignment between galaxies and their dark matter subhalos (M. Velliscig et al. 2015). This misalignment is expected to influence the strength of IA of galaxies with the large-scale structure, motivating studies of accurately accounting for such a discrepancy. Furthermore, a decrease in the misalignment angle would somehow permeate the IA amplitude with respect to redshift.

As in Figure 16, no significant redshift evolution of ANLA is observed for galaxies. This result is consistent with the assumption of the NLA model, which assumes that the IA is “frozen" at the time of galaxy formation. Dark matter subhalos show a mild redshift evolution of ANLA with a nonzero power-law slope of 0.509 over 3σ from zero. During galaxy formation, the tidal field of the large-scale structure influences the distribution of collapsing matter, which leads to IAs. As the Universe evolves, the large-scale structure evolves as well. When the overdense region becomes more overdense, some dark matter subhalos undergo matter accretion that disturbs the internal structure, and others may lose a portion of their structure because of the tidal stripping. Thus, the intrinsic shape of dark matter subhalos changes, which might potentially weaken previously established alignments. However, galaxies are typically centered within their own dark matter subhalos from the time of formation, a region where the gravitational potential is strongest. The gravitational potential of their dark matter subhalos shields them somewhat from the external effects of large-scale structure evolution. In addition, the shape of stabilized early-type galaxies will be less affected by internal baryonic processes of galaxies because the star formation, which affects the shape of galaxies, can be suppressed due to the AGN and/or SN feedback (e.g., K. Schawinski et al. 2007; Y.-P. Li et al. 2018). As discussed above, these interpretations regarding the underlying dynamical processes are consistent with the earlier suggestions made by F. Rodriguez et al. (2024). Therefore, these galaxies tend to be stabilized gravitationally within their subhalos and preserve their intrinsic shapes, which induces the decrease in the misalignment angle probability as in Figure 10 (A. K. Bhowmick et al. 2020; K. Xu et al. 2023), and then breeds the lowering of the difference of ANLA between galaxies and dark matter subhalos. This fundamental difference between galaxies and dark matter subhalos emphasizes the resultant trends in ANLA.

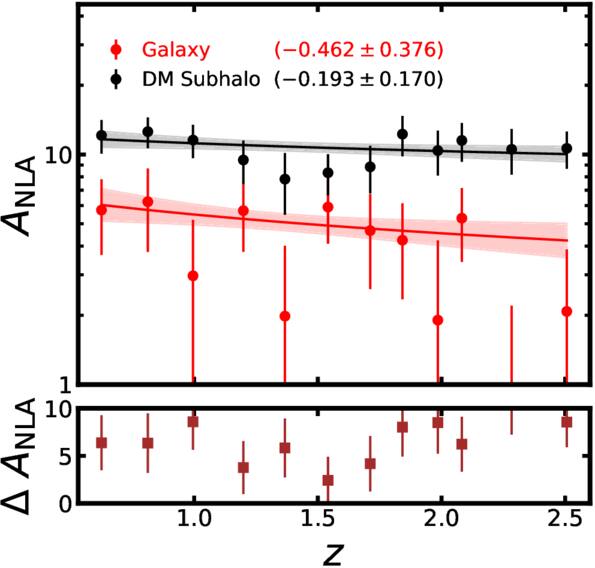

5.3.2. Caveats

In this work, we select early-type galaxies above a given mass. This approach includes galaxies that become massive at lower redshifts, which can introduce biases in interpreting the redshift evolution of the IA amplitude, as the sample reflects an evolving galaxy population rather than tracking the evolution of individual systems. To better trace galaxy evolution, a density-limited selection may be more appropriate. We investigate such a case by fixing the sample size to match that at z = 2.5. We find evolutionary trends in individual ANLA values for subhalos and galaxies that are different from the case of the mass-limited sample, with slopes of −0.193 ± 0.170 and −0.462 ± 0.376 (see Appendix C for figures). The subhalos show relatively constant ANLA, while galaxies have higher ANLA toward low redshifts. However, the trend in ΔANLA and the misalignment angle distribution remains qualitatively consistent with the main results with a mass-limited sample, supporting the view that the decrease in misalignments leads to a reduction in the gap between the IA of galaxies and their host subhalos.

We calculate the strength of the IA by assuming a scenario in which the shape of a galaxy at a given point in time is determined by the density field of the matter at that time. It is inherent in this process that comparison of the relation between the dynamical timescale of galaxies and the cosmic timescale for the tidal field is required. Previous observations of red galaxies have shown that this is a valid assumption (B. Joachimi et al. 2011; S. Singh et al. 2015; H. Johnston et al. 2019, 2021; S. Samuroff et al. 2023). However, considering the formation and evolution of galaxies, red, elliptical, and quiescent galaxies are generally known to be the result of galaxies starting from disk galaxies and undergoing processes such as merging (H. Mo et al. 2010). If the IA is determined at the time of galaxy “formation,” it would imply that galaxies acquire their shape during the formation process. However, in most cases, the shape of an early-type galaxy represents the final stage of morphological evolution, where the galaxy has reached a stable state (e.g, quenched star formation, dynamical equilibrium).

In this context, measuring the strength of the IA at each redshift is a mixed measure of the extent to which the shape of the galaxies formed at that time is related to the gravitational potential of the density field, and the extent to which galaxies formed in the past lose their IA signal through relaxation. Therefore, we should consider this complexity and the fact that the ANLA depends on the epoch of the surrounding structure when we measure the IA amplitude.

6. Conclusions

In this study, we investigate the IA of early-type galaxies and their dark matter subhalos using the HR5 simulation. To do this, we classify early-type galaxies using stellar mass and kinematic information of the galaxies at each redshift. We measure the shape parameters using the reduced inertia tensor from the position and mass information of each stellar particle and dark matter particle. We use two-point statistics to detect the IA correlation between galaxies (dark matter subhalos) and the large-scale structure, and quantify the strength of the IA based on the NLA model. The main findings of our work are summarized as follows:

- (i)We measure and compare the IA correlation function for mass-limited early-type galaxies at z = 0.625, 1.0, and 2.0, and find no significant redshift dependence. The IA signal of dark matter subhalos is consistently stronger than that of galaxies at all redshifts. To quantify the IA strength, we adopt the NLA model and find that galaxies show no redshift evolution in AIA, while subhalos exhibit a mild evolution, as indicated by the best-fit power-law slope.

- (ii)By dividing the sample by stellar mass and measuring the IA strength, we confirm that IA increases with stellar mass at different redshifts. Galaxies and dark matter subhalos exhibit different IA trends with respect to the kinematic criterion based on ∣Vr/σV∣. For galaxies, the signal weakens as the threshold increases, whereas no similar trend is observed for dark matter subhalos. The difference is likely because higher ∣Vr/σV∣ thresholds include a larger fraction of late-type galaxies, which weakens the IA signal, whereas the shapes of dark matter subhalos are largely unaffected by galaxy type.

- (iii)The IA signal does not show significant differences depending on either the method of shape measurement (reduced or standard inertia tensor) or the direction of the projection axis.

- (iv)We compare our findings with previous observations and simulations that show weakly evolving trends of the IA. For galaxies, the amplitude of IA matches well with observations. The trend of our results for galaxies is consistent with N. Chisari et al. (2016), A. Tenneti et al. (2015b), and S. Samuroff et al. (2021) for the redshift range considered. For dark matter subhalos, our results agree with those of T. Kurita et al. (2021).

Our results show that the IA amplitude of galaxies does not evolve with redshift, whereas that of dark matter subhalos does. However, the measured strength of the IA would depend on the modeling approach, which also incorporates how astronomical objects evolve under gravitational potential. Nevertheless, the redshift-independent feature of the IA strength of galaxies may provide useful hints about the extent to which IA may contaminate the lensing signal in future surveys.

Acknowledgments

We thank our referee for providing a helpful report to enhance the manuscript. This work is supported by the Center for Advanced Computation at the Korea Institute for Advanced Study. H.S.H. acknowledges the support of Samsung Electronics Co., Ltd. (project No. IO220811-01945-01), the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT), NRF-2021R1A2C1094577, and Hyunsong Educational & Cultural Foundation. M.T. and S.H. were supported by NRF grant No. 2022R1F1A1064313. J.L. is supported by the National Research Foundation (NRF) of Korea grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT, RS-2021-NR061998). C.P. and J.K. are supported by KIAS individual grants (PG016903, KG039603) at the Korea Institute for Advanced Study. This work benefited from the outstanding support provided by the KISTI National Supercomputing Center and its Nurion Supercomputer through the Grand Challenge Program (KSC-2018-CHA-0003, KSC-2019-CHA-0002). Large data transfer was supported by KREONET, which is managed and operated by KISTI. Y.K. is supported by KISTI under the institutional R&D project K25L2M2C3.

Appendix A: Simple Inertia Tensor

In this appendix, we investigate the effect of the shape measurement method on the IA signal and amplitude. We first compare the shape parameters obtained by the simple (unweighted) inertia tensor to those of the reduced inertia tensor. To do this, we define the simple inertia tensor as follows:

The terms in Equation (A1) are identical to those in Equation (1). We evaluate the eigenvectors and eigenvalues of the tensor, and estimate the shape parameters.

Figure A1 shows a comparison of shape parameters obtained by the reduced and simple inertia tensor. In the left and middle panels, we find that the shapes with reduced inertia tensor are more elliptical than those obtained with the simple inertia tensor. This is in contrast with the results of N. Chisari et al. (2015). However, we note that our definition of the ellipticity is different from the definition that they used. The definition of the weights,  , is also different from what we use. They define

, is also different from what we use. They define  the three-dimensional distance of the stellar particle to the center of the galaxy as the spherically symmetric weights, while we utilize the elliptical weights. We also note that N. Chisari et al. (2015) did not classify the galaxy when they analyzed the ellipticity of the galaxy. The right panel displays the misalignment angle distributions, which are similar to each other.

the three-dimensional distance of the stellar particle to the center of the galaxy as the spherically symmetric weights, while we utilize the elliptical weights. We also note that N. Chisari et al. (2015) did not classify the galaxy when they analyzed the ellipticity of the galaxy. The right panel displays the misalignment angle distributions, which are similar to each other.

Figure A1. Comparison of shape parameters obtained by the simple inertia tensor to those of the reduced inertia tensor. Left: total ellipticity distributions of galaxy and dark matter subhalo. Middle: the ratio between the semimajor and semiminor axes of a galaxy. Right: misalignment angle distribution.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageFigure A2 displays IA correlation and the amplitude of IA. In the left panels, the IA correlation does not show a significant dependence on the shape measurement. In the right panel, ANLA shows a similar trend to that shown in the left panel. Galaxy (dark matter subhalo) whose shape is obtained by simple inertia tensor displays a very slightly higher (lower) amplitude than the reduced inertia tensor case. However, considering the difference, it is not statistically significant and does not change the overall trend. Our test shows inconsistent results against N. Chisari et al. (2016), who compare the effect of the shape measurement method (Figure 11 therein). Their results show that the amplitude of IA for an elliptical galaxy whose shape is obtained by the simple inertia tensor is much larger than the reduced inertia tensor case. However, as we noted, the scale of the correlation measurement is different from ours, and the weights imposed in the reduced case are different. Also, the difference shown in the bottom panels is similar to zero, so that the systematics of shape measurement do not affect the trend of redshift evolution.

Figure A2. Comparison of IA correlation and the amplitude of IA. In the top panels, the empty circles (squares) represent galaxy (dark matter subhalo) IA correlation (top left panel) and ANLA (top right panel), whose shapes are measured through the reduced inertia tensor. The filled symbols indicate the results of the simple inertia tensor. In the bottom panels, orange circles (light gray squares) represent the difference of galaxy (dark matter subhalo) IA correlation between simple and reduced inertia tensor.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageAppendix B: Grid Locking

In this appendix, we test the possibility of the contamination of the “grid-locking” effect in our results. The simulations based on AMR technique, such as RAMSES, tend to show that the spins of galaxies are aligned with the simulation grid vector (O. Hahn et al. 2010; Y. Dubois et al. 2014; S. Codis et al. 2015b). This is a well-known issue that the grid-locking effect occurs in the Cartesian-based Poisson solver when calculating the force from gravitational potential (A. May & R. A. James 1984; R. W. Hockney & J. W. Eastwood 2021). In particular, the tendency for the spin to be artificially aligned with the grid vector seems better seen in low-mass galaxies, and in galaxies with lower redshifts (O. Hahn et al. 2010; M. Danovich et al. 2012). Because the spin of a galaxy is one tracer of its orientation, the fact that the spin shows numerical errors due to the grid-locking effect suggests the possibility that it affects the orientation of the galaxy and, by extension, biases the IA of the galaxy.

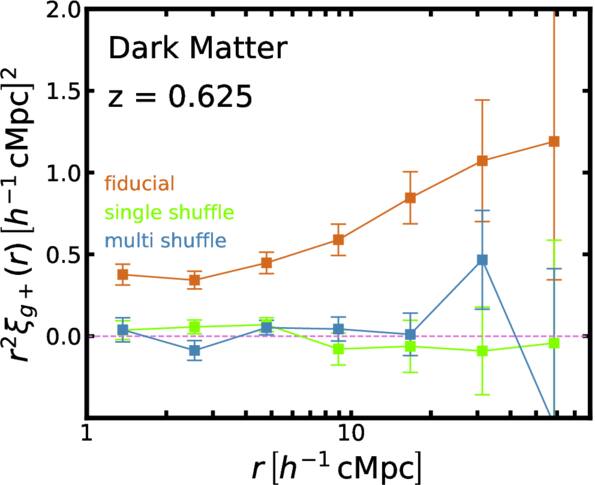

We therefore verify whether the IA signal of HR5 galaxies is likely to be contaminated by these phenomena. To do this, we adopt the method of S. Codis et al. (2015b). Because we are interested in the alignment between the shape and the density field, not the spin, we compute the same statistics by randomly permuting the shape parameters, ellipticity, and position angle, while keeping the density field fixed by keeping the galaxy position unchanged. The random permutation removes the physical two-point correlation signal. If the IA signal is biased by grid locking, then random shuffling of the shape will not change the number or orientation of the grid-locked objects, so the correlation will appear regardless of the permutation. Figure B1 shows the results of measuring the IA correlation for single-shuffled and multi-shuffled cases with the original IA signal at z = 0.625. The two-point correlation is consistent with the null (zero), no matter how many times we shuffle. We confirm that the shape parameters of the galaxy were not affected by the grid-locking effect and that the IA signal we measured has a physical origin.

Figure B1. The correlation function used to examine the grid-locking effect. The ellipticity and position angle are randomly mixed once and several times. The position of dark matter subhalos remains without a shuffle. We multiply ξ(r) by r2 for presentation purposes. We only show the correlation of dark matter subhalos for clarity, but we confirm that the correlation of galaxies is consistent with dark matter subhalos. Shuffled results indicate that the shape of the galaxy and dark matter subhalo are not affected by the grid-locking effect.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageAppendix C: ANLA for Density-limited Samples

In this appendix, we display the redshift dependence of ANLA for the density-limited samples discussed in Section 5.3.2. We select ∼1300 massive early-type galaxies at z = 2.5 and keep this sample density at low redshifts. Figure C1 shows the distribution of the misalignment angle for the density-limited case. Figure C2 exhibits the redshift evolution of ANLA for this case.

Figure C1. Similarly to Figure 10, the distribution of misalignment angles for density-limited samples evolves with redshift.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageFigure C2. Similar to Figure 16, but for the density-limited samples.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution image