Abstract

A core-collapse supernova (CCSN) provides a unique astrophysical site for studying neutrino–matter interactions. Prior to the shock-breakout neutrino burst during the collapse of the iron core, a preshock νe burst arises from the electron capture of nuclei and it is sensitive to the low-energy coherent elastic neutrino–nucleus scattering (CEνNS) which dominates the neutrino opacity. Since the CEνNS depends strongly on nonstandard neutrino interactions (NSIs), which are completely beyond the standard model and yet to be determined, the detection of the preshock burst thus provides a clean way to extract the NSI information. Within the spherically symmetric general-relativistic hydrodynamic simulation for the CCSN, we investigate the NSI effects on the preshock burst. We find that the NSI can maximally enhance the peak luminosity of the preshock burst almost by a factor of three, reaching a value comparable to that of the shock-breakout burst. Future detection of the preshock burst will have critical implications on astrophysics, neutrino physics, and physics beyond the standard model.

Original content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 licence. Any further distribution of this work must maintain attribution to the author(s) and the title of the work, journal citation and DOI.

1. Introduction

Neutrinos interact feebly with ordinary matter (Wolfenstein 1999). Nonetheless, they play a critical role in a core-collapse supernova (CCSN), which marks the death of massive stars with mass ≳8 M⊙ and leaves behind a compact remnant (see Woosley et al. 2002; Janka 2012; Burrows & Vartanyan 2021, for reviews). In a CCSN, most (∼99%) of the released gravitational potential energy (∼1053 erg) of the progenitor star is ultimately liberated through neutrino emission within a ∼10 s burst. Neutrinos from CCSNe can thus carry invaluable information on both CCSN and neutrino physics (Koshiba 2003).

Meanwhile, the discovery of neutrino oscillations (Fukuda et al. 1998; Ahmad et al. 2002) indicates neutrinos are massive and lepton flavors are mixed, providing solid experimental evidence of physics beyond the standard model (SM). Current and upcoming neutrino experiments can measure subdominant neutrino oscillation effects that are expected to give information on the yet-unknown neutrino parameters and the nonstandard interactions (NSIs) between neutrinos and matter (Wolfenstein 1978; Ohlsson 2013; Farzan & Tórtola 2018; Bhupal Dev et al. 2019). Note that the NSI are completely originated from new physics beyond the SM and not an expected consequence of existing theories or neutrino oscillations. The NSI can modify the production, propagation, and detection of neutrinos and thus may crucially affect the interpretation of the relevant experimental data. While the oscillation experiments can put important constraints on the NSI parameters, nonoscillation data (e.g., from neutrino-scattering experiments) are needed to break the possible degeneracy of the neutrino parameters allowed by oscillation data alone (Coloma et al. 2017). Indeed, the deep inelastic neutrino-scattering experiments (e.g., CHARM, Dorenbosch et al. 1986; and NuTeV,Zeller et al. 2002) can help to break degeneracy but the constraints apply only if the NSI are generated by mediators not much lighter than the electroweak scale. For light mediators (Denton et al. 2018), the degeneracy can only be broken through combination with results on coherent elastic neutrino–nucleus scattering (CEνNS), which was predicted in the 1970s (Freedman 1974) but observed only recently by the COHERENT Collaboration (Akimov et al. 2017, 2021).

Indeed, a global fit to neutrino oscillation and CEνNS data indicates that the degeneracy of neutrino parameters is significantly disfavored for a wider range of NSI models (Esteban et al. 2018; Farzan & Tórtola 2018; Coloma et al. 2020). Although significant progress has been made on constraining the NSI parameters by analyzing data on neutrino oscillations, deep inelastic neutrino scattering, and CEνNS, some NSI parameters are still not well constrained. In particular, the vector-like quark-νe

neutral current (NC) couplings,  and

and  , are the least experimentally constrained (Esteban et al. 2018; Farzan & Tórtola 2018; Coloma et al. 2020), preserving parameter space large enough to cause sizable modifications in the CEνNS cross sections. Compared to the case of charged-current (CC) NSI, it is a much more daunting task to constrain NC NSI due to the experimental and theoretical difficulties. Because of the frequent CEνNS in a CCSN, the CCSN can thus provide an ideal site for constraining the NC NSI parameters. Recently, Suliga & Tamborra (2021) estimate the NSI effects on neutrino–nucleon scattering in the postbounce SN core within the diffusion time criterion wherein the neutrinos cannot be trapped for too long. In this work, we show that the neutrino burst from the preshock neutronization in a CCSN can be used as a novel and clean probe of the NC NSI parameters

, are the least experimentally constrained (Esteban et al. 2018; Farzan & Tórtola 2018; Coloma et al. 2020), preserving parameter space large enough to cause sizable modifications in the CEνNS cross sections. Compared to the case of charged-current (CC) NSI, it is a much more daunting task to constrain NC NSI due to the experimental and theoretical difficulties. Because of the frequent CEνNS in a CCSN, the CCSN can thus provide an ideal site for constraining the NC NSI parameters. Recently, Suliga & Tamborra (2021) estimate the NSI effects on neutrino–nucleon scattering in the postbounce SN core within the diffusion time criterion wherein the neutrinos cannot be trapped for too long. In this work, we show that the neutrino burst from the preshock neutronization in a CCSN can be used as a novel and clean probe of the NC NSI parameters  and

and  .

.

2. Preshock Neutronization Burst

Modern CCSN models (O’Connor et al. 2018) have commonly predicted the existence of the so-called neutronization neutrino burst with a peak luminosity ∼4 × 1053 erg s−1, which emerges during the first ∼25 ms after the core bounce as a result of sudden breakout of a flood of neutrinos freshly produced in shock-heated matter (and some νe produced previously that have diffused to the neutrinosphere) when the bounce shock penetrates the neutrinosphere and reaches the neutrino-transparent regime at sufficiently low densities. This shock-breakout burst mainly comprises νe from electron captures on free protons in the shock-heated matter.

Prior to the shock-breakout burst, a smaller burst exists that is due to νe

produced from the preshock neutronization of the collapsing core (Liebendörfer et al. 2003; Kachelrieß et al. 2005; Wallace et al. 2016; O’Connor et al. 2018). This preshock burst emerges as a result of the competition between the νe

emission due to electron captures on nuclei during the early neutronization stage of core collapse and νe

trapping due to the opacity enhancement as the density and temperature of the core increase. Although the preshock burst is weaker than the shock-breakout burst, it generally has weaker model dependence in the CCSN simulations since it only involves relatively simpler dynamics in the early stage of the CCSN. In particular, the preshock burst is expected to strongly depend on the CEνNS cross sections which essentially control the neutrino opacity in the preshock stage (Bruenn & Mezzacappa 1997), and thus to provide a clean probe of the NC NSI parameters  and

and  . It should be noted that the NC interactions change the neutrino opacity without directly changing the neutrino production rate which is mainly determined by the CC electron capture processes (Sullivan et al. 2016; Langanke et al. 2021).

. It should be noted that the NC interactions change the neutrino opacity without directly changing the neutrino production rate which is mainly determined by the CC electron capture processes (Sullivan et al. 2016; Langanke et al. 2021).

3. NSI Effects on Neutrino–nucleus Scattering

Following the spirit of effective four-fermion couplings in low-energy weak interactions, the NC NSI Lagrangian can be typically formulated as (Ohlsson 2013; Farzan & Tórtola 2018; Bhupal Dev et al. 2019)

where GF is the Fermi constant;  denotes the NSI parameters with

denotes the NSI parameters with  corresponding to an NSI strength comparable to that of SM weak interactions; α, β ∈ {e, μ, τ} represent neutrino flavors; f ∈ {e, u, d} is the matter field; and PX

with X = L(R) represents the left(right) chirality projection operator. The NSI parameters are flavor-diagonal for α = β, while the lepton flavor is violated and the NSI becomes flavor-changing for α ≠ β. Here we mainly focus on the flavor-diagonal NC vectorial NSI couplings of νe

to the light quarks, i.e.,

corresponding to an NSI strength comparable to that of SM weak interactions; α, β ∈ {e, μ, τ} represent neutrino flavors; f ∈ {e, u, d} is the matter field; and PX

with X = L(R) represents the left(right) chirality projection operator. The NSI parameters are flavor-diagonal for α = β, while the lepton flavor is violated and the NSI becomes flavor-changing for α ≠ β. Here we mainly focus on the flavor-diagonal NC vectorial NSI couplings of νe

to the light quarks, i.e.,

since they have relatively larger parameter space with ![${\varepsilon }_{{ee}}^{{uV}}({\varepsilon }_{{ee}}^{{dV}})\in [0.0,0.5]$](https://content.cld.iop.org/journals/2041-8205/923/2/L26/revision1/apjlac4014ieqn9.gif) while the amplitude of other NSI parameters has been tightly constrained to be ≲0.1 (Esteban et al. 2018; Farzan & Tórtola 2018; Coloma et al. 2020). Note the SNO results (Aharmim et al. 2008) agree well with the prediction of the standard solar model, suggesting small NSI axial interactions and thus

while the amplitude of other NSI parameters has been tightly constrained to be ≲0.1 (Esteban et al. 2018; Farzan & Tórtola 2018; Coloma et al. 2020). Note the SNO results (Aharmim et al. 2008) agree well with the prediction of the standard solar model, suggesting small NSI axial interactions and thus  . With

. With  , the effective NSI couplings to nucleons can thus be obtained as

, the effective NSI couplings to nucleons can thus be obtained as

For neutrino–matter interactions, we use here the neutrino interaction library NuLib (O’Connor 2015). In order to investigate the effects of the NC NSI parameters εu

and εd

, we modify the cross sections of the following isoenergetic reactions, νe

+ α

νe

+ α, νe

+ p

νe

+ α, νe

+ p

νe

+ p, νe

+ n

νe

+ p, νe

+ n

νe

+ n,

νe

+ n,  , and the corresponding reactions induced by

, and the corresponding reactions induced by  . For (anti-)neutrino–nucleus scattering, the cross section includes three corrections (Burrows et al. 2006): the ion–ion correlation function

. For (anti-)neutrino–nucleus scattering, the cross section includes three corrections (Burrows et al. 2006): the ion–ion correlation function  , the form factor term

, the form factor term  and the electron polarization correction

and the electron polarization correction  . The expressions of the three corrections remain unchanged since they are irrelevant to the NC NSI parameters εu

and εd

. For simplicity, we neglect the weak magnetism corrections for antineutrinos (Horowitz 2002) since here we mainly focus on the neutronization burst in the early stage of CCSN, which mainly involves νe

. In such a case, the cross section modification is rather straightforward, namely, we only need to replace the NC vector couplings

. The expressions of the three corrections remain unchanged since they are irrelevant to the NC NSI parameters εu

and εd

. For simplicity, we neglect the weak magnetism corrections for antineutrinos (Horowitz 2002) since here we mainly focus on the neutronization burst in the early stage of CCSN, which mainly involves νe

. In such a case, the cross section modification is rather straightforward, namely, we only need to replace the NC vector couplings  and

and  in the SM, respectively, by

in the SM, respectively, by  and

and  as

as

Correspondingly, the cross section expression is modified by replacing the weak charge of nucleus  by

by  as

as

The ratio of the neutrino–nucleus cross sections with and without NSI can be expressed as  (Burrows et al. 2006) if we neglect the corrections from

(Burrows et al. 2006) if we neglect the corrections from  and

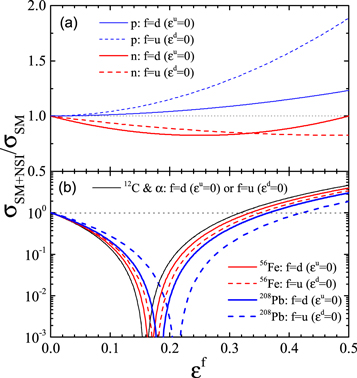

and  . To examine the NSI effects on neutrino–nucleus scattering, we plot in Figure 1 the ratio σSM + NSI/σSM as a function of εd

(εu

= 0) or εu

(εd

= 0) for several typical nuclei, i.e., α, 12C, 56Fe and 208Pb, as well as protons (p) and neutrons (n). One sees that the neutrino–nucleus cross sections can be drastically suppressed and even vanish around a certain value of εd

(εu

) depending on the isospin of the nucleus. This is due to the fact that the effective weak charge

. To examine the NSI effects on neutrino–nucleus scattering, we plot in Figure 1 the ratio σSM + NSI/σSM as a function of εd

(εu

= 0) or εu

(εd

= 0) for several typical nuclei, i.e., α, 12C, 56Fe and 208Pb, as well as protons (p) and neutrons (n). One sees that the neutrino–nucleus cross sections can be drastically suppressed and even vanish around a certain value of εd

(εu

) depending on the isospin of the nucleus. This is due to the fact that the effective weak charge  may vanish for a certain value of εd

(εu

) satisfying the relation

may vanish for a certain value of εd

(εu

) satisfying the relation  , where Yp

= Z/A is the proton fraction of the nucleus. One can easily find

, where Yp

= Z/A is the proton fraction of the nucleus. One can easily find  when εu

+ εd

= 0.159 for nuclei with N = Z (e.g., α, 12C), and for more neutron-rich nuclei (e.g., 56Fe, 208Pb) with smaller Yp

,

when εu

+ εd

= 0.159 for nuclei with N = Z (e.g., α, 12C), and for more neutron-rich nuclei (e.g., 56Fe, 208Pb) with smaller Yp

,  generally leads to larger εd

(εu

), as shown in Figure 1. On the other hand, the neutrino-p(n) cross section exhibits relatively weak sensitivity to εd

or εu

. These features will lead to a number of interesting consequences on the neutrino burst in CCSN.

generally leads to larger εd

(εu

), as shown in Figure 1. On the other hand, the neutrino-p(n) cross section exhibits relatively weak sensitivity to εd

or εu

. These features will lead to a number of interesting consequences on the neutrino burst in CCSN.

Figure 1. Neutrino–nucleon (a) and neutrino–nucleus (b) scattering cross sections divided by their SM model values as functions of the NSI parameter εd (εu = 0) or εu (εd = 0).

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution image4. NSI Effects on Neutrino Burst

SN core collapse and bounce are simulated using the spherically symmetric general-relativistic hydrodynamic code GR1D (O’Connor & Ott 2010; O’Connor 2015). As a default of the CCSN simulation, we adopt the 15 M⊙ solar-metallicity progenitor star (s15s7b2) from Woosley & Weaver (1995), and the SFHo equation of state (EOS) from Steiner et al. (2013) is used to describe the physics of stellar matter. Figure 2 shows the time evolution of all-flavor neutrino number and energy luminosities in the initial two stages of CCSN, i.e., the infall phase and neutronization burst, with εu = 0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5 (εd = 0). The later two stages of the accretion phase and Kelvin–Helmholtz cooling phase are not shown for simplicity since our main focus is the preshock burst.

Figure 2. Time evolution of the total neutrino number (a) and energy (b) luminosities for the stellar collapse of a 15 M⊙ solar-metallicity progenitor star using the SFHo EOS with various εu values (εd = 0).

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageFor all the εu

values considered here, it is clearly seen from Figure 2 that the luminosity displays two peaks, i.e., the smaller one around the bounce and the larger one after the bounce, respectively corresponding to the preshock burst and the shock-breakout burst. In particular, we note (although not shown here) that the preshock burst essentially consists of only νe

, and the shock-breakout burst (around the peak) is also dominated by νe

with ≲15% heavy-flavor (anti-)neutrinos and tiny (≲1%)  . In addition, the average νe

energy of the preshock burst is ∼10 MeV. For the shock-breakout burst, the average energy is ∼14 MeV for νe

, ∼15 MeV for heavy-flavor (anti-)neutrinos and ∼10 MeV for

. In addition, the average νe

energy of the preshock burst is ∼10 MeV. For the shock-breakout burst, the average energy is ∼14 MeV for νe

, ∼15 MeV for heavy-flavor (anti-)neutrinos and ∼10 MeV for  . These general features also have been observed in various modern CCSN simulations (O’Connor et al. 2018).

. These general features also have been observed in various modern CCSN simulations (O’Connor et al. 2018).

The most interesting feature illustrated in Figure 2 is the NSI effects on the two bursts, i.e., while the variation of the peak luminosity for the shock-breakout burst with εu

is a little complicated and relatively weak (≲10%), the corresponding variation for the preshock burst is rather straightforward and very drastic. For the latter, the peak luminosity first increases with εu

varying from 0 to 0.2, and then decreases as εu

changes from 0.2 to 0.5. Such a variation is mainly due to the NSI effects on the neutrino–nucleus scattering. As shown in Figure 1, increasing εu

from 0 to ∼0.2 will reduce drastically the neutrino–nucleus cross section and even make it vanish at εu

∼ 0.2, and the cross section enhances again as εu

increases from ∼0.2 to 0.5. During the early neutronization stage of CCSN, the νe

, e−, and nuclei are dominant and the CEνNS decisively controls the neutrino opacity (Bruenn & Mezzacappa 1997). The suppression of neutrino–nucleus scattering will increase a neutrino’s mean free path and thus enhance neutrino emission. Quantitatively, it is remarkable to see from Figure 2 that the peak number (energy) luminosity of the preshock burst can reach to ∼2.1 × 1058 s−1 (∼3.9 × 1053 erg s−1) for u

= 0.2, which is significantly larger than and almost three times the corresponding value of without NSI (i.e., ∼0.86 × 1058 s−1 (∼1.3 × 1053 erg s−1) for

u

= 0), and it even becomes comparable to the corresponding result of the shock-breakout burst (i.e., ∼2.5 × 1058 s−1 (∼6.0 × 1053 erg s−1)).

It is interesting to see that the peak luminosity of the shock-breakout burst does not much depend on the NSI, and this is understandable since the shock-breakout burst neutrinos are mainly produced through electron captures on free protons in the shock-heated matter and escape in the neutrino-transparent regime at sufficiently low densities where the neutrino–nucleus scattering is less important. The neutrino–nucleon scattering in the shock-heated matter may give rise to opacity and thus influence the neutrino emission of the shock-breakout burst, but the NSI effects are relatively weak as shown in Figure 1(a). Moreover, the preshock burst may also slightly influence the shock-breakout burst since the former affects the νe 's distribution behind the neutrinosphere. Furthermore, modern CCSN simulations (O’Connor et al. 2018) indicate some sensitivity of the shock-breakout burst height and shape to the details of the neutrino transport, while the preshock burst is relatively robust due to the much simpler dynamics involved. Therefore, our results suggest that the preshock burst of CCSN should be a clean probe of the NSI.

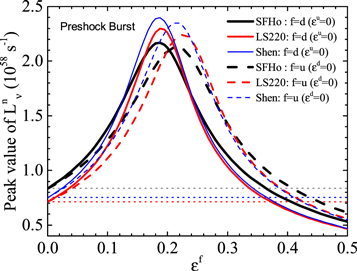

To examine the robustness of the preshock burst as a probe of εf , we show in Figure 3 the peak number luminosity of the preshock burst as a function of εd (εu = 0) and εu (εd = 0) using three different EOSs, i.e., the default SFHo EOS, the LS220 EOS from Lattimer & Swesty (1991) with nuclear matter incompressibility K0 = 220 MeV and Shen EOS from Shen et al. (2011). One sees that the difference of the peak number luminosity from the three EOSs is relatively small (∼10%). The weak EOS dependence is mainly due to the small difference of low-density (≲1012 g cm−3) stellar matter EOS for the three EOSs since the preshock burst mainly involves stellar matter with density up to the neutrino-trapping value (∼1012 g cm−3). Indeed, using the Lattimer and Swesty EOSs (Lattimer & Swesty 1991) with K0 = 180 MeV and 375 MeV which give very different EOS around and above nuclear density (≳1014 g cm−3) but the same low-density EOS, we find the resulting peak number luminosities are almost the same as that with K0 = 220 MeV. In addition, one sees from Figure 3 that the εf maximizing the peak number luminosity is larger than that minimizing the νe -56Fe cross section as shown in Figure 1, and this is mainly because the 56Fe nuclei in the collapsing core are transformed into more neutron-rich nuclei due to electron captures and thus larger εf is needed to minimize the νe -nucleus cross sections as discussed previously.

Figure 3. The total number luminosity peak value of the preshock burst vs. the NSI parameter εf for the stellar collapse of the 15 M⊙ solar-metallicity progenitor star with three different EOSs, i.e., SFHo, LS220, and Shen. The dotted lines show the SM values for each EOS.

Download figure:

Standard image High-resolution imageWe also note the preshock burst only weakly depends on the progenitor mass, consistent with earlier findings (Takahashi et al. 2003; Kachelrieß et al. 2005; Wallace et al. 2016). Nevertheless, the progenitor property can be constrained with multimessenger signals (O’Connor & Ott 2013; Mukhopadhyay et al. 2020; Warren et al. 2020; Barker et al. 2021; Segerlund et al. 2021) once the source is detected. Moreover, the more realistic three-dimensional (3D) simulations (Nagakura et al. 2021) give very similar predictions on the neutronization burst during the early stage of CCSN as the one-dimensional (1D) simulations adopted here, further justifying the robustness of the preshock burst as a probe of εf . In addition, the nonstandard neutrino self-interactions (NSSI) are not considered here. Although the NSSI may significantly modify the neutrino-flavor transformation and thus influence the neutrino spectra (Dighe & Sen 2018; Yang & Kneller 2018; Lei et al. 2020), they are not expected to cause sizable modification to our results unless the NSI neutrino–neutrino coupling gν can be significantly larger than the NSI neutrino–quark coupling gq (e.g., gν ≳ 90gq ). This is because the NSSI only have minor impact on the neutrino opacity due to the small νe fraction and cross section compared to those of nuclei in the early collapsing core. It will be interesting to see the NSSI effects on the preshock burst when the gν is extremely large (e.g., gν ≳ 90gq ).

In Figure 3, we consider only two extreme cases by independently varying εd (εu = 0) or εu (εd = 0), and the results with simultaneous variation of εd and εu should be between the corresponding results of the two extreme cases. Moreover, due to the quadratic dependence of the CEνNS cross section on the weak charge, there inevitably exists εf degeneracy for a fixed peak luminosity of the preshock burst. In particular, Figure 3 displays degeneracy for εf = 0 and εf ∼ 0.4. The combined analysis of neutrino oscillation and CEνNS experiments perhaps can break the degeneracy. As pointed out in (Farzan & Tórtola 2018), εd ≃ 0.3 is more favored than εd = 0 at a level of 2 σ in analyses of solar neutrino experiments. Recently, the COHERENT collaboration report their new measurement of CEνNS on Argon, excluding the parameter region around εf ∼ 0.2 with 90% C.L. (Akimov et al. 2021). Nevertheless, the peak luminosity of the preshock burst still keeps great sensitivity to the NSI in the remaining parameter space.

It is instructive to have a discussion on the experimental detection of the preshock burst. Although neutrino oscillation should not lead to major modifications to the core-collapse dynamics (Chakraborty et al. 2011; Dasgupta et al. 2012; Stapleford et al. 2020), it will largely distort the νe

emission pattern in terrestrial detectors. Hence, it is better to use all-flavor detection to depict the temporal structure of the preshock burst. Recently, Raj (2020) shows the feasibility of detecting neutrino number luminosity from a failed CCSN using large-scale DM detectors, from which we note the detection of the preshock burst is possible if a source is located within ∼1 kpc. Luckily, such presupernova stars are not too rare in our galaxy, and a list of 31 candidates within 1 kpc, including the famous Betelgeuse, is rendered in Mukhopadhyay et al. (2020). In addition, the εf

reduces the detection rate of the detectors made of nuclei but has no effects on the neutrino–electron cross sections and even enhances the neutrino-p cross sections, and therefore the detectors made of protons or electrons should be an ideal choice. As an example, we estimate the detection potential of εu

by the Hyper-Kamiokande (Abe et al. 2018) via the electron-scattering channel. Using the sntools (Migenda et al. 2021) code to simulate the detector response for the preshock burst from a 1 kpc CCSN, we find the event count per 1 ms can reach  around the preshock burst peak. By assuming

around the preshock burst peak. By assuming  , we find the discovery region of εu

with 3σ is [0.015, 0.388] ⊕ [0.415, 0.5] for no neutrino oscillation and [0.033(0.023), 0.373(0.380)] ⊕ [0.438(0.424), 0.5] for the oscillation scenario with normal (inverted) neutrino-mass ordering. Furthermore, it is important to note that the flavor-blind measurement via the elastic neutrino-p scattering, e.g., in JUNO (An et al. 2016), can avoid the influence of oscillation and even break the degeneracy at εf

∼ 0.4 due to the NSI enhancement of neutrino-p cross sections as shown in Figure 1(a). Such a detection configuration of JUNO is yet to be added in sntools.

, we find the discovery region of εu

with 3σ is [0.015, 0.388] ⊕ [0.415, 0.5] for no neutrino oscillation and [0.033(0.023), 0.373(0.380)] ⊕ [0.438(0.424), 0.5] for the oscillation scenario with normal (inverted) neutrino-mass ordering. Furthermore, it is important to note that the flavor-blind measurement via the elastic neutrino-p scattering, e.g., in JUNO (An et al. 2016), can avoid the influence of oscillation and even break the degeneracy at εf

∼ 0.4 due to the NSI enhancement of neutrino-p cross sections as shown in Figure 1(a). Such a detection configuration of JUNO is yet to be added in sntools.

Finally, we note that the enhancement of neutrino emission in the preshock burst can reduce the central electron fraction Ye of the CCSN, e.g., the central Ye after the bounce is reduced from 0.281 to 0.247 as εu varies from 0 to 0.2. This reduction of Ye may influence the later neutrino flavor evolution, explosion dynamics, and nucleosynthesis (Kajino et al. 2019; Cowan et al. 2021) of the CCSN. Reliable predictions on these topics are beyond the 1D simulations, and it will be extremely interesting to explore them within the more realistic 3D simulations (Nagakura et al. 2021). In addition, it is worth noting that the detection of the preshock burst may provide a clean way to extract neutrino oscillation information and determine the neutrino-mass hierarchies (Takahashi et al. 2003; Kachelrieß et al. 2005; Wallace et al. 2016).

5. Conclusion

We have demonstrated that the preshock neutrino burst in a CCSN can serve as a clean probe of the largely unknown NSI parameters  and

and  . In particular, our results indicate that the NSI can enhance the peak luminosity of the preshock burst almost by a factor of three and make the luminosity comparable to that of the shock-breakout burst, which will have critical implications on the explosion dynamics of CCSNs. Future detection of the preshock burst will open a new window to extract information on the CCSN, the NSI, the neutrino oscillation, and the neutrino-mass hierarchies.

. In particular, our results indicate that the NSI can enhance the peak luminosity of the preshock burst almost by a factor of three and make the luminosity comparable to that of the shock-breakout burst, which will have critical implications on the explosion dynamics of CCSNs. Future detection of the preshock burst will open a new window to extract information on the CCSN, the NSI, the neutrino oscillation, and the neutrino-mass hierarchies.

The authors thank Jianglai Liu, Chuanle Sun, and Donglian Xu for useful discussions. This work was supported by the National SKA Program of China No. 2020SKA0120300 and the National Natural Science Foundation of China under grant No. 11625521.

Software: GR1D (O’Connor & Ott 2010; O’Connor 2015), NuLib (O’Connor 2015), sntools (Migenda et al. 2021).